Prof. Rankin Discusses Smoke in Mirror Politics that Keep People Homeless

Freedom. For many of us, it is a notion, a word that carries many meanings. These meanings might vary from person to person, depending upon their needs or situation. But freedom is more than a philosophical concept for those who have truly lost theirs.

Homeless people are a prime example of this. In many cases, homeless people have lost the freedom to engage in some of the most basic life-sustaining activities just because they are homeless. Visibly homeless people run the risk of being arrested just for existing in public. The prison system then strips them of whatever few rights they had left. Upon release from incarceration, their likelihood of remaining homeless actually increases. Criminalizing homelessness comes at the expense of their livelihood. It also costs cities tens of millions of dollars. Decades worth of studies continues to prove that it is significantly less expensive to house homeless people than it is to criminalize their actions.

Today, we sat down with criminalization expert Professor Sara Rankin who explained why cities still choose handcuffs over housing and sweeps over shelters. The answer is as heartbreaking and infuriating as homelessness itself.

Professor Sara Rankin

“Criminalizing homelessness has been shown to be the least effective and most expensive way of managing homelessness.”~Professor Sara Rankin, criminalization expert

Invisible People:

Good Afternoon Professor Rankin. I would like to start our interview by thanking you on behalf of Invisible People for your hard work and dedication to homeless rights advocacy. Our publication is aimed at giving homeless people a voice and identity beyond the often-negative portrayal seen in other forms of media. We are well aware of the fact that perception often fuels criminalization and that criminalization exacerbates homelessness. We look forward to your professional opinion in regards to this issue and other issues that touch the homeless community. I always let our speakers introduce themselves in their own words before I begin my questions. How would you describe yourself to readers who might not already be familiar with your work?

Professor Sara Rankin:

I am a professor of law at Seattle University School of Law where I also direct the Homeless Rights Advocacy Project. HRAP, aka The Homeless Rights Advocacy Project, engages students of all majors, but primarily law students, in research analysis and advocacy around constitutional and civil rights issues that people experiencing homelessness confront.

At HRAP, we select the topics that we research in partnership with people from the community who come to us and let us know of issues that they need extra researcher analysis on in order to help support their advocacy or legislative work. We’ve got about 17 reports on different topics that are available on our webpage. You can turn to our site to access other resources and research compiled by our partners as well. This research not only applies to Washington, but also to other cities along the West Coast and throughout the country.

Invisible People:

That is wonderful to hear. Your organization has influenced a great deal of change and generated mass public appeal. What inspired you to become involved in this line of work?

Professor Sara Rankin:

I used to be in private practice as an attorney and I did a lot of pro bono immigration work and the bench that were doing work for immigrants seeking asylum was pretty small. Incidentally, a bench, is a legal term that means “group of attorneys”. There’s always a need for more attorneys doing immigration work.

While doing that work, what I found was how consistently issues relating to race, nationality, and immigration status intersected with poverty and housing instability. I noticed there were people who were focusing on some of those other dimensions, but nobody was really focusing on their legal needs with respect to housing instability. That’s how I initially got interested in this sort of work. Then I just started meeting more attorneys, scholars, and activists throughout the country who were concerned about the same things as me.

Invisible People:

In addition to being a legal professional and activist, you are also a teacher. We like to think of our readers as students of life and social justice issues. If you could teach our readers anything about homelessness and criminalization, what would it be?

Professor Sara Rankin:

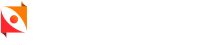

I think I’d first say that they should look to someone like Mark and talk to people with lived experience if they really wanted to get an education. In terms of the information that I can share, I think that imprecision in language it is a big part of the problem. A lot of times we use vague terms when we talk about homelessness and that makes it really difficult and confusing for the general public to understand.

For example, I think most people don’t understand the difference between general homelessness, unsheltered homelessness, and chronic homelessness in particular. Other things that all too often go unexplained include:

- What some of the main major causes of homelessness might be

And

- What some of the most effective interventions might be

These are extremely important for the public to understand so they know which solutions will work in which situations.

I’ll give you an example … Something like rapid re-housing or housing vouchers might be a really effective intervention for families experiencing homelessness, but those same tactics won’t be particularly effective for people experiencing chronic homelessness.

Another example is this … Most of the general public doesn’t understand the difference between affordable housing, which is really just keyed off of the median income someone makes, and supportive housing, which includes other services for formerly homeless people. Also, and this is very important, too … When we talk about affordable housing, we must consider the big question: affordable to whom?

Invisible People:

While we’re on the topic of technical definitions, could you please explain what the criminalization of homelessness is for readers who might not be familiar with that phrase?

Professor Sara Rankin:

In a legal context, homeless criminalization applies to laws and policies that prohibit or severely restrict one’s ability to engage in necessary life-sustaining activities in public, even when that person has no reasonable alternative. Examples would be laws that prohibit or severely restrict one’s ability to:

- Receive food

- Ask for help

- Protect themselves from the elements

- Sit

- Stand

- Sleep

- Go to the bathroom

These are basic things that nobody can survive without doing.

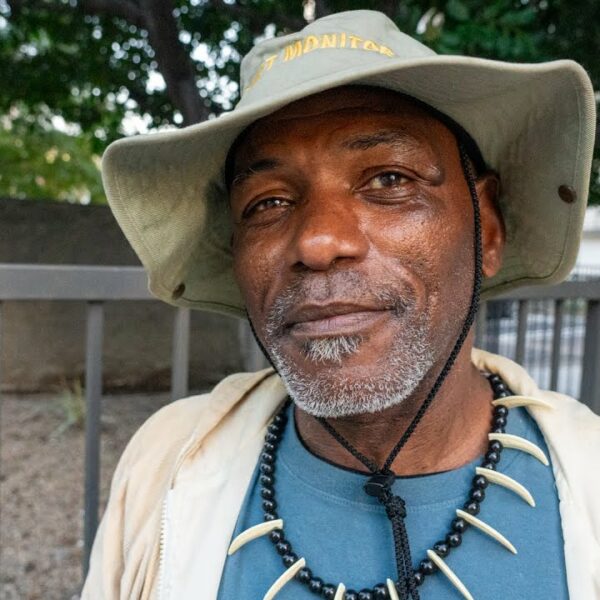

When we talk about the criminalization of homelessness, the main focus of the discussion revolves around people who are visibly homeless … so, folks who are unsheltered and particularly folks who are chronically homeless. There is a technical definition used to determine when somebody is experiencing chronic homelessness. By definition, this person has not only been homeless longer and more frequently, but they also have to suffer from a qualifying disabling condition that prevents them from working.

The presence of that secondary disabling condition helps to explain the persistence of their homelessness. If an uneducated person sees someone who’s experiencing chronic homelessness, they might wonder why they don’t just get a job. The answer, of course, is because they can’t get a job. The fact that the general public doesn’t know that shows their lack of understanding about what it means to be chronically homeless. Furthermore, in instances of chronic homelessness, popular solutions like job training and rental assistance do not apply. In order for the general public to understand that, they have to know the definition of chronic homelessness.

Invisible People:

You are quoted saying that we as a society enforce laws that aim to make poverty less visible in public spaces? What is it about extreme poverty that makes us subconsciously afraid to witness it in person, even though we all know it exists?

Professor Sara Rankin:

It’s highly likely that we reject because of the fear that it could be us. Not necessarily consciously, but the primal part of the brain is based in very complex and layered fears that people have. Fears of poverty, suffering, and desperation … The very thought of just falling through the cracks of society terrifies us on a subconscious level.

We also have a deep-rooted instinct to exile people who seem undesirable or non-compliant with our expectations. There is a sociologist from Princeton by the name of Professor Susan Fiske who studies stereotypes and prejudice. From her neurological studies, we see how negatively housed people respond to visibly homeless people. These studies are not ones where people report their feelings. They are based solely on the brain’s reaction to imagery. In such studies, people respond to evidence of visible homelessness with higher rates of negativity then they do when they’re exposed to any other marginalized trait. This includes traits that we historically associate with discrimination like race or gender.

We are deeply wired to react negatively to images that we associate with unsheltered homelessness. This tells you how difficult criminalization is to overcome. Throughout American history, we have always tried to confine, incarcerate, and persecute people who appear to be poor or otherwise undesirable. What we’re dealing with is a cesspool of ignorance, stereotypes, and prejudice, combined with a historically proven commitment to purging public space of any evidence of visible poverty or homelessness.

People don’t like to hear that their reaction to visible poverty is a form of discrimination and prejudice that plays a significant role in criminalization. But it absolutely does.

It’s sort of like talking to white people about white privilege. It’s a treacherous, but at the same time, necessary discussion.

Invisible People:

Can you discuss the drawbacks of criminalizing homelessness as opposed to rectifying it?

Professor Sara Rankin:

Put simply, criminalizing homelessness has been shown to be the least effective and most expensive way of managing homelessness. When you add up all the factors, the process of criminalizing someone actually makes them more likely to remain homeless. It does nothing to improve their condition or the condition of the economy.

There’s a lot of studies that show it is 2 to 3 times more expensive to leave someone who is chronically homeless unsheltered right where they are than it is to provide that same person with permanent, supportive housing.

Invisible People:

Let’s discuss why it costs so much more to do nothing.

Professor Sara Rankin:

Essentially, we end up spending a ton of money on emergency room services, hospitalization, law enforcement, the legal system, the jail system, the probation system, etc. This is not to mention the extraordinary emotional and psychological costs that develop as a consequence of experiencing homelessness. For more details, please refer to our research paper Penny Wise But Pound Foolish: How Permanent Supportive Housing Can Prevent a World of Hurt. It shows five decades of studies that prove this same point over and over.

Invisible People:

We recently did a piece based on one of your tweets about negative language in the media. Do you see a good deal of negative terminology regarding the homeless population? Can you speak on how that impacts both criminalization and the homeless community at large?

Professor Sara Rankin:

You see it all the time. There’s definitely a tendency to paint people who are homeless as criminals, animals, portraying them as blameworthy, or having caused their own circumstances. These tactics dehumanize and justify the continued systemic persecution so it feeds the whole cycle. The language that we use helps to justify and keep people vulnerable.

Invisible People:

Do you find that legislation targeting the homeless community has changed over the years? If so, would those changes translate as better, worse, or equal?

Professor Sara Rankin:

The National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty has been surveying 187 cities. They have determined there have been significant increases in the enactment of these criminalization laws. These laws punish people for surviving in a public space. We have a report called the Wrong Side of History, which discusses this in detail. These laws are not new at all. They’ve been around a long time. But I do think that the ways they are enforced has become more complex.

Side note: For an in-depth look at the history of criminalization, Sara Rankin, Matthew Dick, and Javier Ortiz released a 39-page essay on the subject entitled The Wrong Side of History: A Comparison of Modern and Historical Criminalization Laws.

Invisible People:

Could you expand on this rather profound statement where you said that, among other things, criminalization makes homeless people more likely to die?

Professor Sara Rankin:

There are really clear connections between living unsheltered and experiencing extraordinary psychological and physical trauma. I wrote an article recently where I was citing a lot of medical studies that show the connection between decreases in mortality and living unsheltered. There is clear proof that the likelihood that you’re going to die if you’re living unsheltered goes up exponentially.

When people are processed through the criminal justice system that processing makes them less likely to be able to use emergency shelters, which makes them less likely to be able to get housing and causes them to remain unsheltered. So, it increases the likelihood that they will eventually die due to lack of shelter.

There is a known connection between housing and health outcomes. That is why so many major healthcare companies have invested millions of dollars in supportive housing and affordable housing.

Invisible People:

Many of our interviewees seem to think homelessness is likely to persist in the future. Judging by your writing, you appear to have a more optimistic take. Do you truly believe that ending homelessness is possible? If so, what do you think is the best approach to ending homelessness and why?

Professor Sara Rankin:

I know it’s possible because there are a number of communities that have made significant progress or have reached what’s called a functional 0. This is a technical term that essentially means they have a manageable number of homeless people in their community. It does not mean that 0 people are homeless.

Study after study after study over decade after decade prove that permanent supportive housing is the most humane and cost-effective solution. Unfortunately, as long as we lack the political will and the public support to prioritize non-punitive solutions like that over tentative solutions like finalization, we’ll continue to tread water, to swim in the wrong direction.

Invisible People:

If permanent supportive housing is such a great solution, why do cities continue to criminalize people?

Professor Sara Rankin:

Firstly, it’s really hard to control the number of myths and stereotypes that most people have about who’s homeless and what homelessness is. But let’s assume we could make progress by educating people about the most humane and cost-effective ways to end homelessness.

In a scenario like that, you still have politicians who are in charge of all these policies. Interventions take time to implement, right? They take time and money and I think that a lot of politicians choose to pursue things like sweeps because it creates the illusion of an immediate solution. So, if I’m a politician with limited tenure, that means I’m only in office for a certain period of time. Under those circumstances, what are my interests in coming up with a plan that will end chronic homelessness in 5 years? Chances are, I’ve got a pretty low interest in doing that because the person who’s going to reap the benefits of that program is going to be someone who is my successor.

On the other hand, if I can pull off the scandal of moving people from one place to the other it creates this smoke and mirrors effect. The general public is then led to believe the problem has been solved when what really happened is the problem was just moved to somebody else’s neighborhood. And at a premium price, too. Los Angeles alone has spent tens of millions of dollars on sweeps and for that matter, so has Seattle. They’ve done nothing to address the underlying problems of homelessness and extreme poverty.

Cities don’t even invest in the people that they’re moving around.

There is no regard for an improved outcome. This should really be intolerable. We, in the public, should be outraged that the cities are literally just throwing money down the drain at the expense of human lives and all in the name of maintaining a falsified public image.

In Conclusion

After speaking with Professor Sara Rankin, it becomes clear that any gain from anti-homeless legislation and its enforcement is merely an illusion.

Here’s the reality. More than half a million people are homeless every night in the United States of America. Over the past decade, criminalization of homelessness has increased and so has the tragedy of homelessness.

At this point, if we remain silent in the face of this truth, we too, become complicit accessories. Be sure to let your legislators know that you are paying attention to the number of anti-homeless laws enforced as opposed to the number of affordable houses being built. Let them know this issue is important to you. If somebody doesn’t set their pride aside and take real action, the crisis will essentially fall square on their shoulders.