What America Believes About Homelessness

Introduction

There is a direct line between how the public views homelessness and the policy choices leaders make. Many blame homelessness on the person experiencing it rather than the shortage of affordable housing, lack of a living wage, childhood trauma, expensive and inaccessible health care, or the countless other reasons that make a person vulnerable to losing their home. This gap between public perceptions and reality creates a cycle of misunderstanding that reduces public support for the policies we need to solve this crisis.

In September of 2020, Invisible People surveyed over 2,500 respondents across 16 cities to understand public attitudes about homelessness, policy preferences, and how the public interprets messages about homelessness. This research explores what people are currently hearing and outlines messaging strategies to reach different public audiences. For policymakers, advocates, service providers, and anyone else working to end homelessness, this report will be a useful tool in building the public support and political will needed to help end homelessness.

Introduction

There is a direct line between how the public views homelessness and the policy choices leaders make. Many blame homelessness on the person experiencing it rather than the shortage of affordable housing, lack of a living wage, childhood trauma, expensive and inaccessible health care, or the countless other reasons that make a person vulnerable to losing their home. This gap between public perceptions and reality creates a cycle of misunderstanding that reduces public support for the policies we need to solve this crisis.

In September of 2020, Invisible People surveyed over 2,500 respondents across 16 cities to understand public attitudes about homelessness, policy preferences, and how the public interprets messages about homelessness. This research explores what people are currently hearing and outlines messaging strategies to reach different public audiences. For policymakers, advocates, service providers, and anyone else working to end homelessness, this report will be a useful tool in building the public support and political will needed to help end homelessness.

Summary

What Does the Public Think about Homelessness?

In communities across the country, homelessness is seen as a major problem that is getting significantly worse. Nearly threequarters of the public believes homelessness has increased in their community in the past year. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the public’s urgency on homelessness, making concerns about the health of unhoused people and a coming wave of evictions and foreclosures top-of-mind for many.

While expert discussions point to income and the availability of affordable housing as the central issue in discussions of homelessness, public perceptions don’t always align with the views of experts. Driven by local news stories and what people see on the streets, public discussion centers on a few of the most visible negative consequences of homelessness: mental illness and addiction. Whether discussing the causes of homelessness or solutions to it, many in the public prioritize concerns about addiction and mental health over concerns about housing. While issues of income and affordability are part of the conversation, the visibility of addiction and mental illness give them an outsized role in the public imagination.

The result is a major gap between the public conversation on homelessness and discussions happening in homelessness policy and research spaces. Effective messaging should work to close that gap, using narratives to move public understanding toward the expert consensus around housing affordability and wages.

BELIEVE HOMELESSNESS INCREASED IN THEIR COMMUNITY THIS YEAR

SAY THE PANDEMIC HAS MADE THE NEED TO HOUSE HOMELESS PEOPLE MORE URGENT

What Does the Public Think about Homelessness?

In communities across the country, homelessness is seen as a major problem that is getting significantly worse. Nearly threequarters of the public believes homelessness has increased in their community in the past year. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the public’s urgency on homelessness, making concerns about the health of unhoused people and a coming wave of evictions and foreclosures top-of-mind for many.

While expert discussions point to income and the availability of affordable housing as the central issue in discussions of homelessness, public perceptions don’t always align with the views of experts. Driven by local news stories and what people see on the streets, public discussion centers on a few of the most visible negative consequences of homelessness: mental illness and addiction. Whether discussing the causes of homelessness or solutions to it, many in the public prioritize concerns about addiction and mental health over concerns about housing. While issues of income and affordability are part of the conversation, the visibility of addiction and mental illness give them an outsized role in the public imagination.

The result is a major gap between the public conversation on homelessness and discussions happening in homelessness policy and research spaces. Effective messaging should work to close that gap, using narratives to move public understanding toward the expert consensus around housing affordability and wages.

BELIEVE HOMELESSNESS INCREASED IN THEIR COMMUNITY THIS YEAR

SAY THE PANDEMIC HAS MADE THE NEED TO HOUSE HOMELESS PEOPLE MORE URGENT

“Homeless people are both vulnerable and strong, victimized and capable, criminalized and innocent, seen and willfully ignored. When I walk by a homeless person, I feel guilty.”

MAN, 40, NEW YORK, NY *

Quoted statements are verbatim responses from survey respondents.

“Many homeless people in my community are dealing with mental health and addiction issues, which leads many of them to theft and violence. When I hear and see this, I am saddened.”

WOMAN, 58, PORTLAND, OR

“Homeless people are both vulnerable and strong, victimized and capable, criminalized and innocent, seen and willfully ignored. When I walk by a homeless person, I feel guilty.”

MAN, 40, NEW YORK, NY *

“Many homeless people in my community are dealing with mental health and addiction issues, which leads many of them to theft and violence. When I hear and see this, I am saddened.”

WOMAN, 58, PORTLAND, OR

How Do We Make Homelessness Messages Resonate?

When forming their opinions on homelessness, most people are starting from what they see on the streets and on local TV news.

On the streets, members of the public notice a new or growing encampment or a person in a moment of crisis, reinforcing perceptions that the system is failing and the problem is getting worse. On local news, people hear a mix of stories eliciting either sympathy or fear, with a focus on specific and sometimes exceptional individuals.

Whether on the news or in public, what grabs people’s attention are often the least representative stories: a person having a crisis in public, or someone whose biography makes their story stand out. Luckily for advocates, the sympathetic stories often resonate most. When asked to remember what they’ve heard about homelessness, people most often recalled examples that pulled at their heart strings or inspired them.

Moving public opinion will require sustained, effective messaging that is credible, authentic, and resonates with members of the public. In order to identify messages that work, we tested 12 different messages covering a range of topics and framings.

“I have seen numerous stories of homeless people blocking access to people's businesses, attacking businesses, customers, homeowners, stealing, and otherwise hurting people.This makes it difficult to help them.”

MAN, 48, AUSTIN, TX

“I think there are a lot of news stories that touch upon the humanity of people. Hearing stories from homeless people that talk about their personal struggles shows me that there is very little difference between me and them.”

WOMAN, 21, LOS ANGELES, CA

How Do We Make Homelessness Messages Resonate?

When forming their opinions on homelessness, most people are starting from what they see on the streets and on local TV news.

On the streets, members of the public notice a new or growing encampment or a person in a moment of crisis, reinforcing perceptions that the system is failing and the problem is getting worse. On local news, people hear a mix of stories eliciting either sympathy or fear, with a focus on specific and sometimes exceptional individuals.

Whether on the news or in public, what grabs people’s attention are often the least representative stories: a person having a crisis in public, or someone whose biography makes their story stand out. Luckily for advocates, the sympathetic stories often resonate most. When asked to remember what they’ve heard about homelessness, people most often recalled examples that pulled at their heart strings or inspired them.

Moving public opinion will require sustained, effective messaging that is credible, authentic, and resonates with members of the public. In order to identify messages that work, we tested 12 different messages covering a range of topics and framings.

“I have seen numerous stories of homeless people blocking access to people's businesses, attacking businesses,customers, homeowners, stealing, and otherwise hurting people. This makes it difficult to help them.”

MAN, 48, AUSTIN, TX

“I think there are a lot of news stories that touch upon the humanity of people. Hearing stories from homeless people that talk about their personal struggles shows me that there is very little difference between me and them.”

WOMAN, 21, LOS ANGELES, CA

“A homeless person was recently evicted from their home, unable to work, afford the bills due to COVID, was staying in their car, with their wife. They are normal people like you or me, down on their luck, and desperately need our help.”

MAN, 35, AUSTIN TX

One message stood out as the most believable and appealing:

Homelessness can happen to anyone – homeless people deserve help, not blame or scorn.

Segmenting Audiences by Homelessness Attitudes

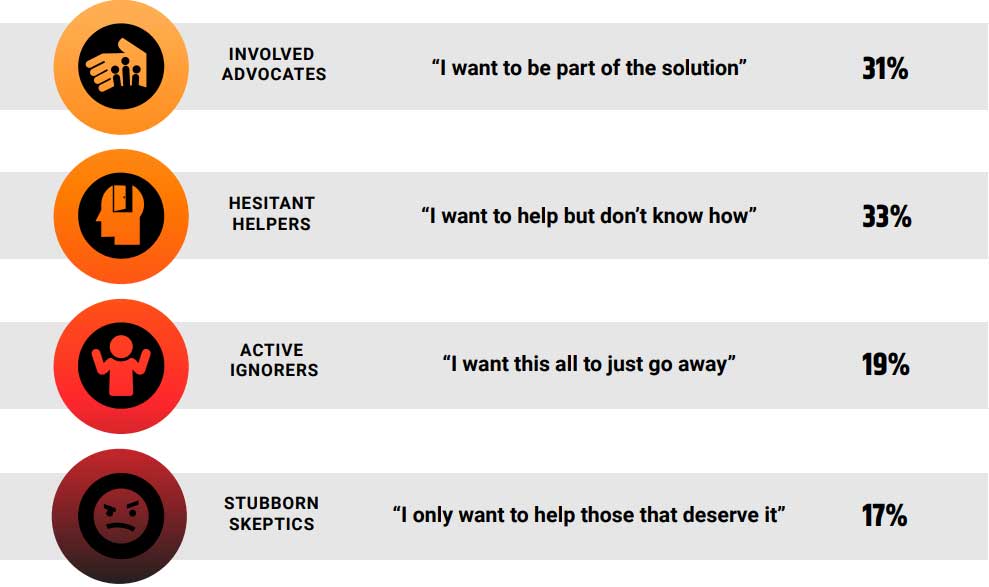

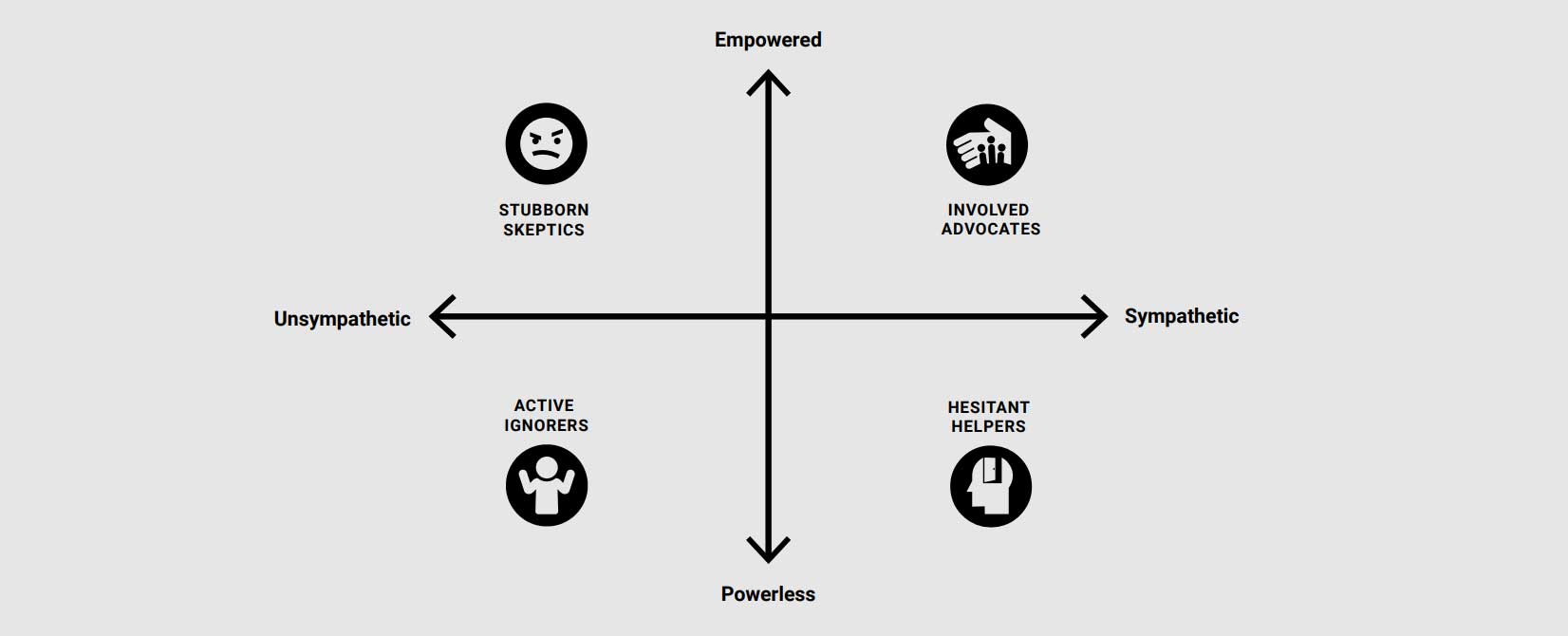

Most messages are targeted at specific audiences, and homelessness messaging is no exception. To better understand these different audiences we identified four segments within the broader public.

“I have seen them take over a lot of public space. They threw their trash all over areas where the city has had to hire people to come out and pick up after them.”

WOMAN, 28, LAS VEGAS, NV

“The police assisted city workers in tearing down tents and taking personal belonging from the homeless! I was so mad, I was angry!”

WOMAN, 52, LOS ANGELES

Segmenting Audiences by Homelessness Attitudes

Most messages are targeted at specific audiences, and homelessness messaging is no exception. To better understand these different audiences we identified four segments within the broader public.

“I have seen them take over a lot of public space. They threw their trash all over areas where the city has had to hire people to come out and pick up after them.”

WOMAN, 28, LAS VEGAS, NV

“The police assisted city workers in tearing down tents and taking personal belonging from the homeless! I was so mad, I was angry!”

WOMAN, 52, LOS ANGELES

“I heard a story about a homeless man that cut other homeless people’s hair. I was impressed by his kindness and the sense of community he had.”

MAN, 41, LOS ANGELES, CA

“The attitudes of some of the local residents are horrific; comments that refer to homeless people as criminal, dirty, subhuman. Comments like ‘get them out of our neighborhood,’ ‘we don't want them,’ ‘they should be put somewhere else,’ ‘they shouldn't be around our children.’”

WOMAN, 66, NEW YORK, NY

Why Messaging Matters

Most people don’t spend very much time thinking about homelessness. Homelessness is something that happens to other people, people who are not like themselves. Their opinions on homelessness are formed based on just a few things they’ve heard or seen.

stories we tell matter as much as the facts we teach and the myths we dispel. Only housing can end homelessness, but telling the right stories is how we get the public on board with housing solutions.

The goal of understanding what the public thinks about homelessness isn’t to capture a static image, but to provide tools to change the narrative. We hope that this research will help advocates, experts, and policymakers tell stories that resonate with the public and move the conversation on homelessness in a more humane and productive direction.

“I heard a story about a homeless man that cut other homeless people’s hair. I was impressed by his kindness and the sense of community he had.”

MAN, 41, LOS ANGELES, CA

“The attitudes of some of the local residents are horrific; comments that refer to homeless people as criminal, dirty, subhuman. Comments like ‘get them out of our neighborhood,’ ‘we don't want them,’ ‘they should be put somewhere else,’ ‘they shouldn't be around our children.’”

WOMAN, 66, NEW YORK, NY

Why Messaging Matters

Most people don’t spend very much time thinking about homelessness. Homelessness is something that happens to other people, people who are not like themselves. Their opinions on homelessness are formed based on just a few things they’ve heard or seen.

stories we tell matter as much as the facts we teach and the myths we dispel. Only housing can end homelessness, but telling the right stories is how we get the public on board with housing solutions.

The goal of understanding what the public thinks about homelessness isn’t to capture a static image, but to provide tools to change the narrative. We hope that this research will help advocates, experts, and policymakers tell stories that resonate with the public and move the conversation on homelessness in a more humane and productive direction.

How the Public Views

Homelessness

The public sees homelessness growing

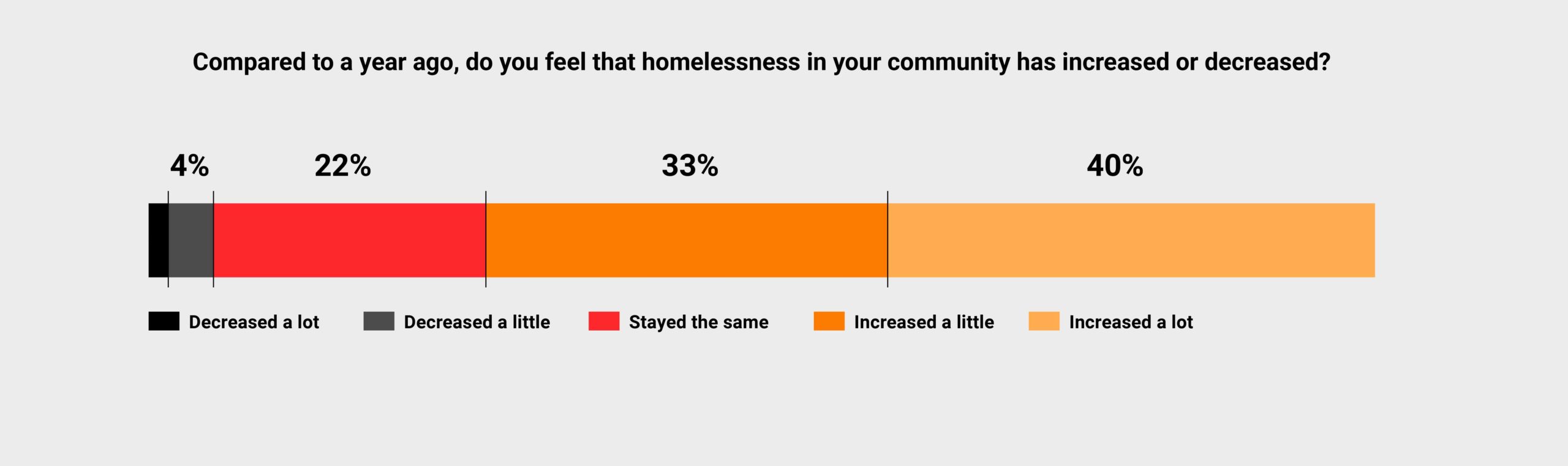

Across the country, the vast majority see more homelessness in their communities than they did a year before. 40% believe that homelessness “increased a lot” over the past year, while just 5% of those surveyed believe homelessness is decreasing in their communities. For the majority of people, the COVID-19 pandemic has only made the issue of homelessness more urgent.

Swipe to View

THINK HOMELESSNESS INCREASED A LITTLE OR INCREASED A LOT IN THEIR COMMUNITY THIS YEAR

SAY THE PANDEMIC HAS MADE THE NEED TO HOUSE HOMELESS PEOPLE MORE URGENT

QA4: Compared to a year ago, do you feel that homelessness in your community has increased or decreased?

The pandemic has made the need to house homeless people more urgent (F)

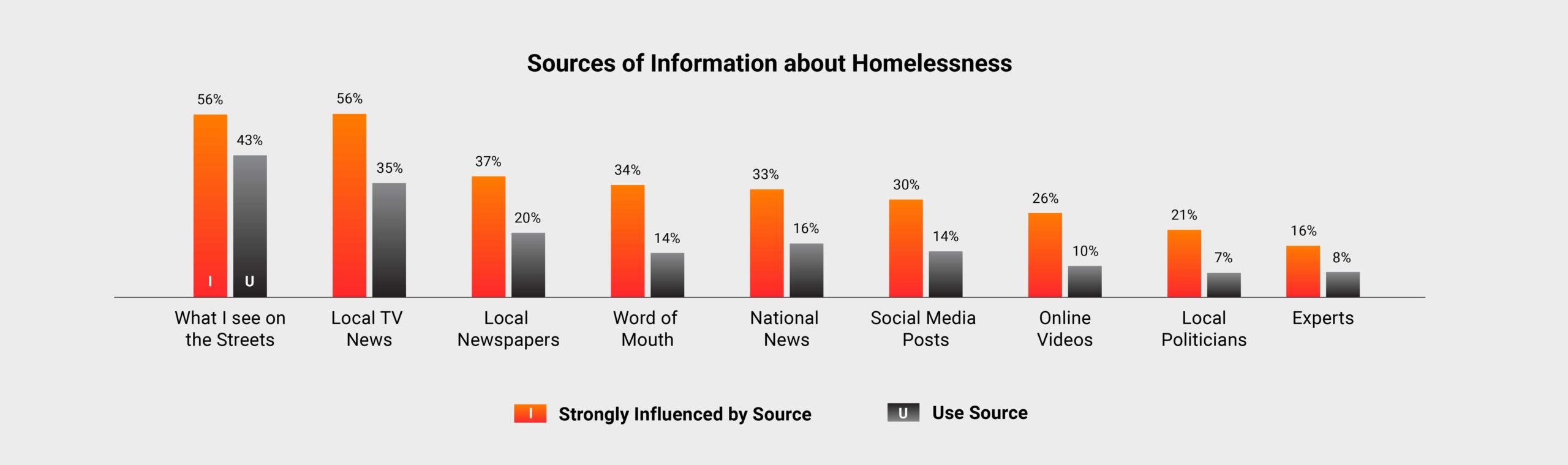

Where is the public learning about homelessness?

The conversation about homelessness is usually rooted in personal experiences and stories from one’s own community from local TV news and what people see on the streets. Over half of the public report they’re strongly influenced by one or both of these sources. Local newspapers and word of mouth also play an important role. National news can have an impact, and major stories are often very memorable, but the day-to-day conversation about homelessness is about local stories and local sources.

Swipe to View

TURN TO LOCAL TV NEWS AND/OR WHAT THEY SEE ON THE STREETS

ARE STRONGLY INFLUENCED BY ONE OR BOTH

QM1: Which of the following sources inform your opinion when you think about homelessness?

QM3: Below are a few sources where you might get information about homelessness. Please rate how much each of the following sources influence your opinions about homelessness?

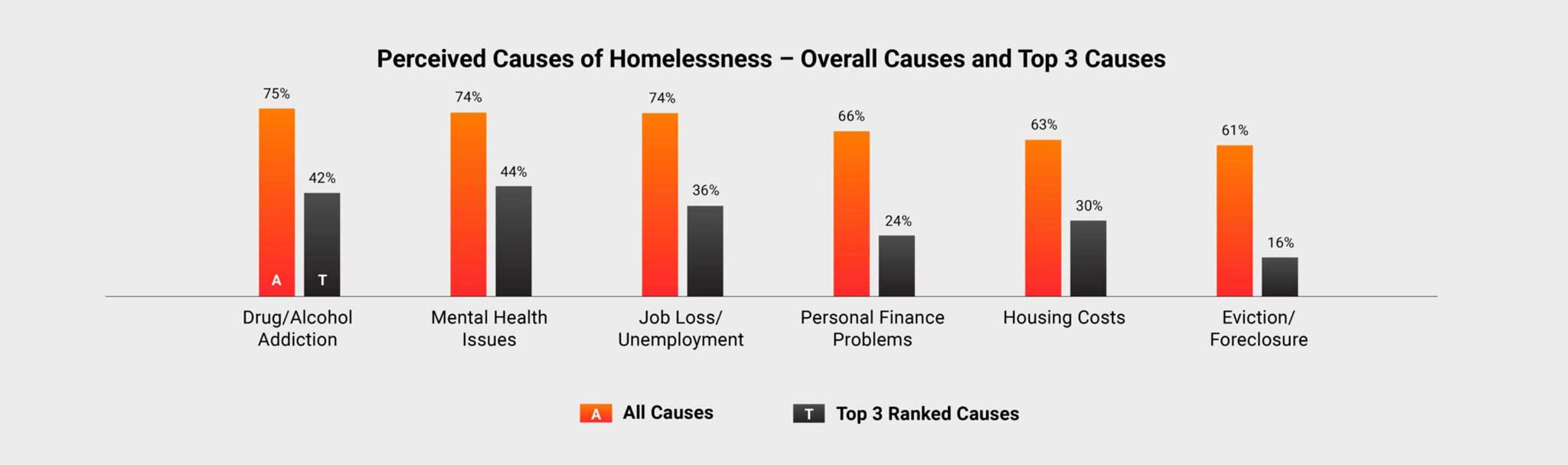

Views on the causes of homelessness

Addiction and mental health issues were considered the most important contributing causes of homelessness, though job loss, housing costs, and other financial considerations follow closely behind. When speaking to the public about homelessness, it’s important to walk a fine line between addressing these concerns and reinforcing myths about the prevalence of addiction and mental illness.

Swipe to View

60% view either addiction or mental illness as a top cause of homelessness.

QA8: Which of the following issues are the biggest causes of homelessness in your community?

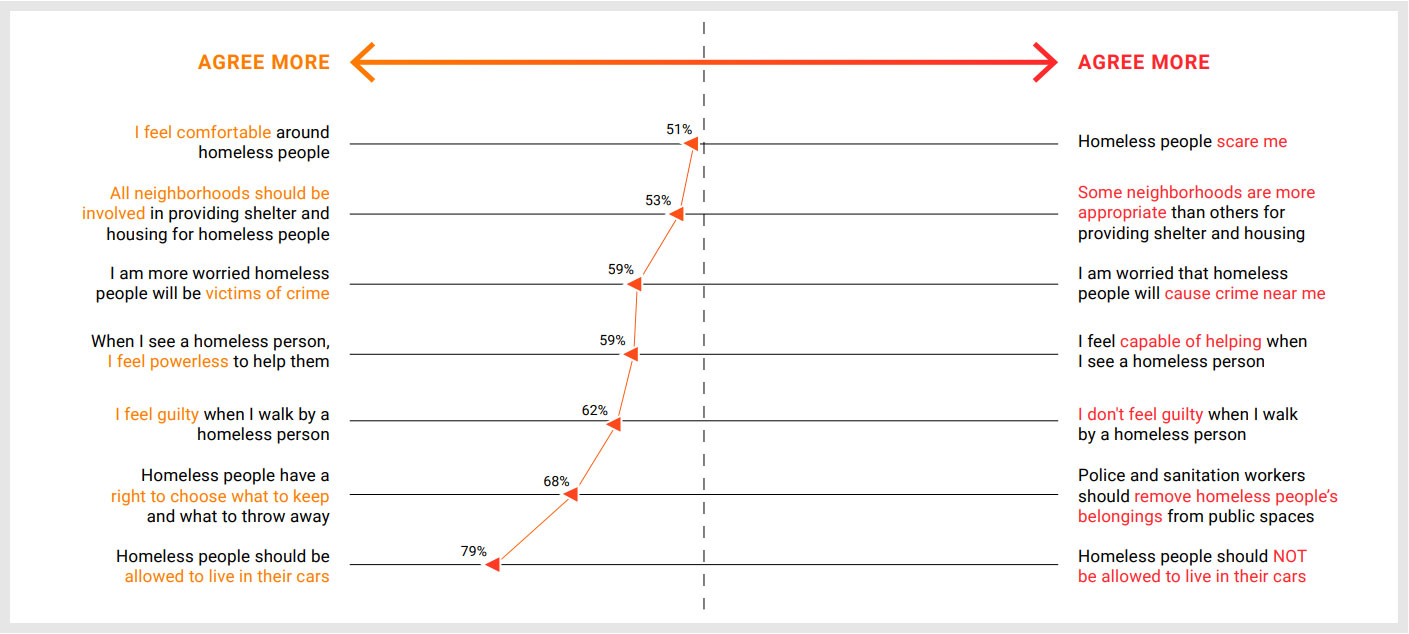

Public attitudes about homeless people

The public is divided in their feelings on homeless people and which neighborhoods should be involved in providing assistance. Around half the public feels scared around homeless people, and many are worried about homeless people committing crimes or simply feel guilty about homelessness. There was more agreement that homeless people should be allowed to sleep in their cars, and that police and sanitation workers should not arbitrarily seize homeless people’s property.

Swipe to View

QA9A: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your feelings about homelessness.

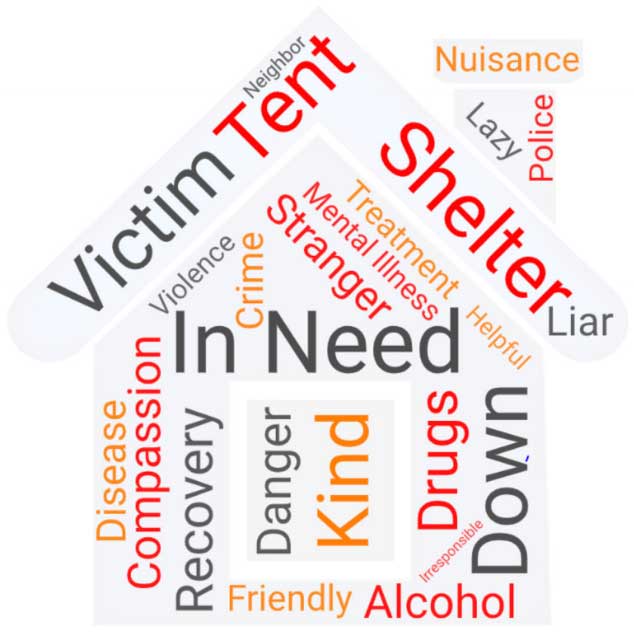

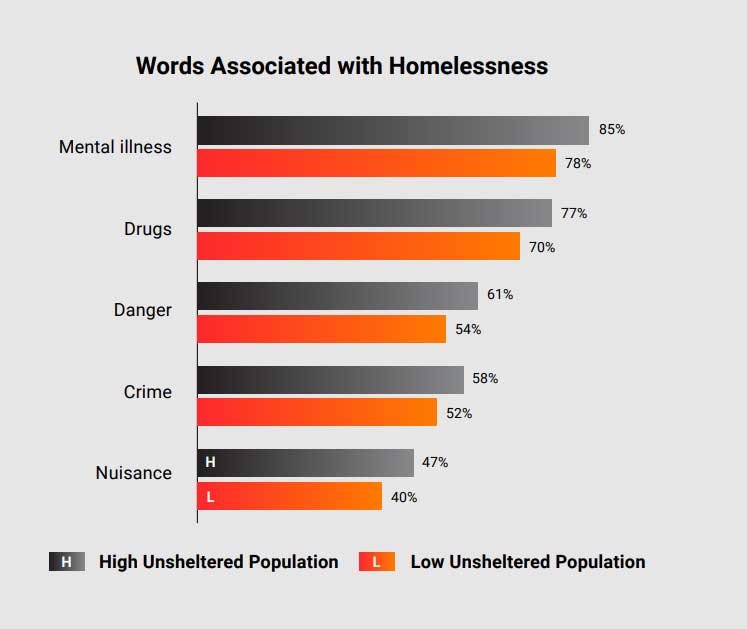

Associations with homelessness

While mental illness and addiction are central in discussing the causes of homelessness, the most common associations people make with homelessness are about need. Some of the most judgmental words, like “lazy” and “irresponsible” were among the least associated phrases, suggesting that, while many have concerns about crime or danger, the majority are ultimately still sympathetic to the needs of unhoused people.

QA6: Next, we’re going to show you a series of words or phrases you may or may not associate with homelessness. If you associate that word or phrase with homelessness or homeless people, press “Agree”, otherwise, press “Disagree.”

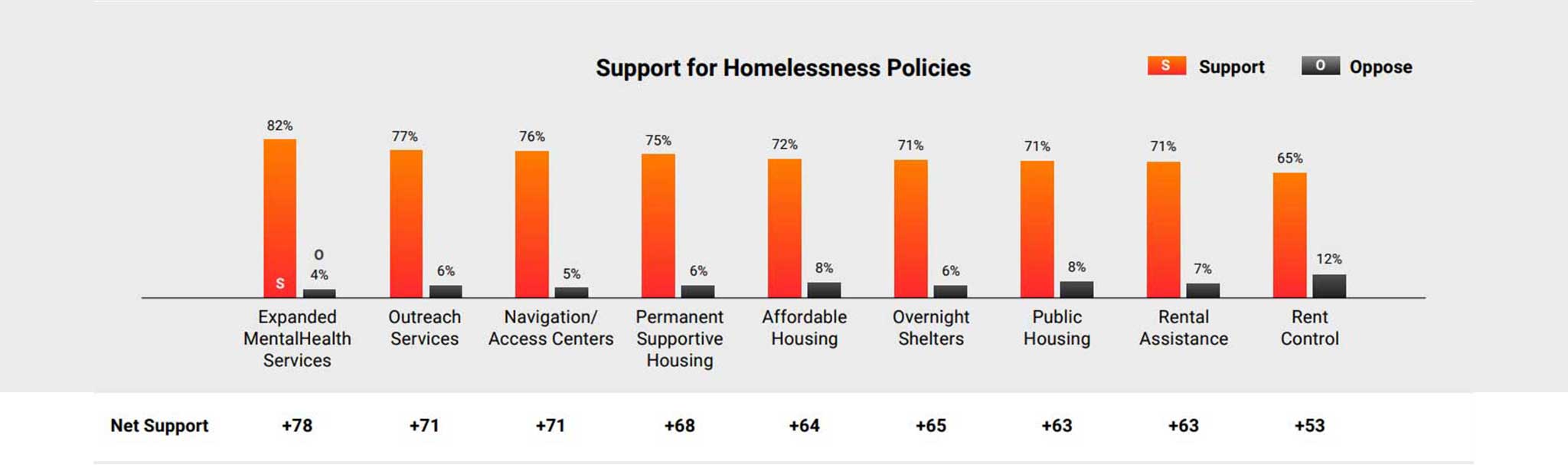

Humane solutions have widespread support

When it comes to homelessness policy, mental health and outreach services are the most popular and face the least opposition, consistent with the public’s focus on mental health and addiction as causes of homelessness. The vast majority of the public is also in favor of a number of pro-housing measures, ranging from permanent supportive housing to public housing to rental assistance aimed at reducing the pipeline into homelessness.

Swipe to View

SUPPORT EXPANDING PERMANENT SUPPORTIVE HOUSING

SUPPORT EXPANDING MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

QA15: Below are a few policies that local governments might implement to address homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

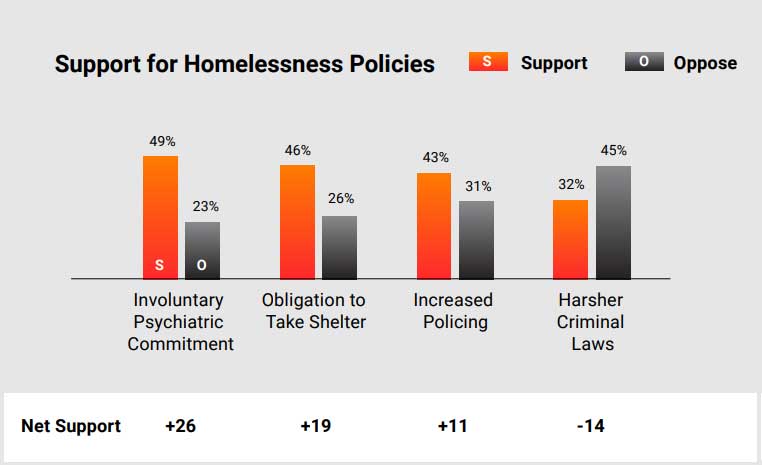

Enforcement-driven solutions are controversial

Solutions that focus on enforcement through civil commitment or policing were the least popular and most controversial policies tested. Harsher criminal laws aimed at policing homeless people were the only policy that generated more opposition than support, with nearly half of respondents opposed to criminalization measures. Involuntary commitment, the most popular of these options, still has significantly less support than any policy promoting housing, shelter, or services.

ARE OPPOSED TO HARSHER CRIMINAL LAWS

QA15: Below are a few policies that local governments might implement to address homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

Drivers of Negative

Sentiment

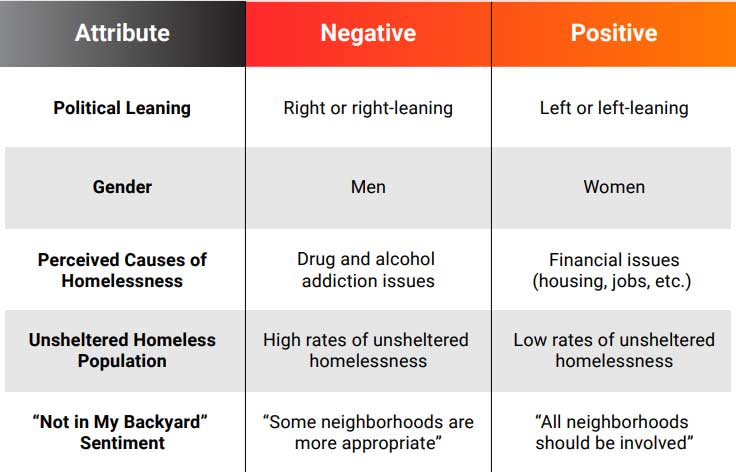

What drives negative sentiment about homelessness?

Negative sentiment about homelessness is correlated with several factors. When it comes to government action on homelessness, people’s political leanings are a major determinant of their attitudes. Gender also contributes, with men offering more punitive views towards homeless people. Perceived causes of homelessness and the size of the local unsheltered population can also drive negative sentiment. Finally, those who hold “not in my backyard” views see homeless people and homelessness projects in a more negative light.

Swipe to View

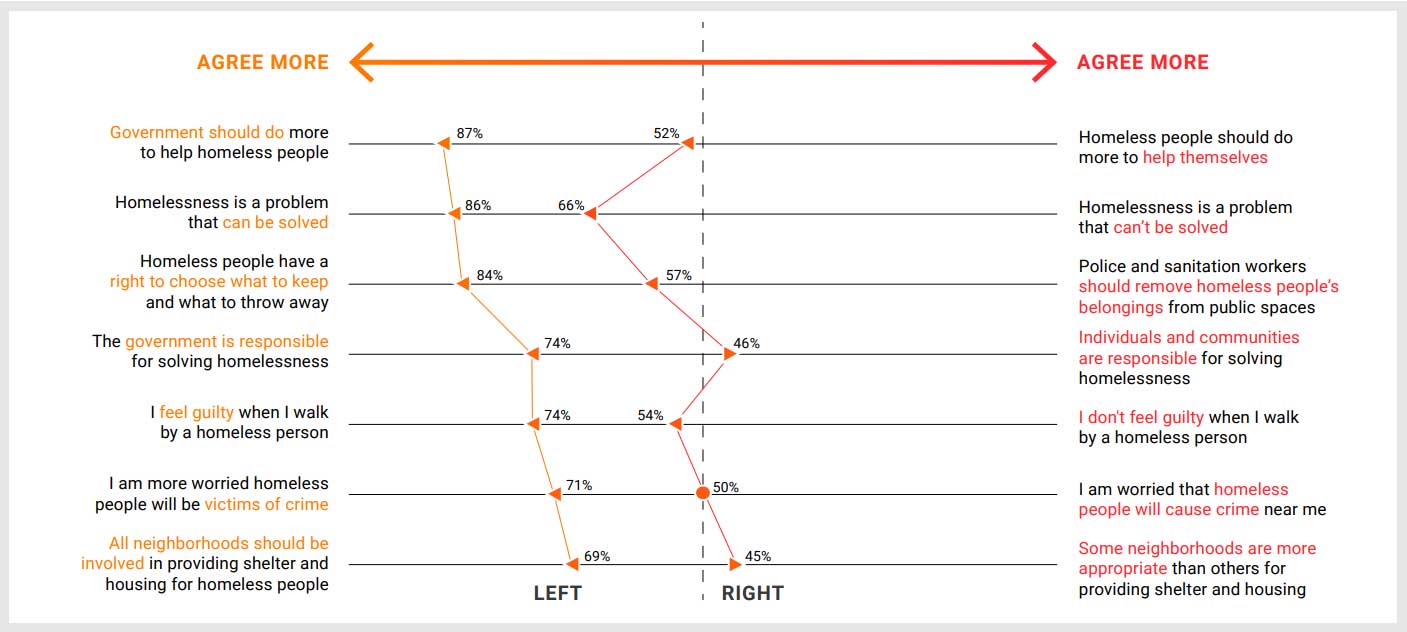

Political leanings inform views on homelessness

Unsurprisingly, conservatives are less enthusiastic about government action on homelessness, though a narrow majority still support government stepping in to help. Those on the left are more lenient towards homeless people using public spaces, feel more guilt when they see homelessness, and are more likely to support homelessness solutions in their own communities.

Swipe to View

QA9A: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your feelings about homelessness.

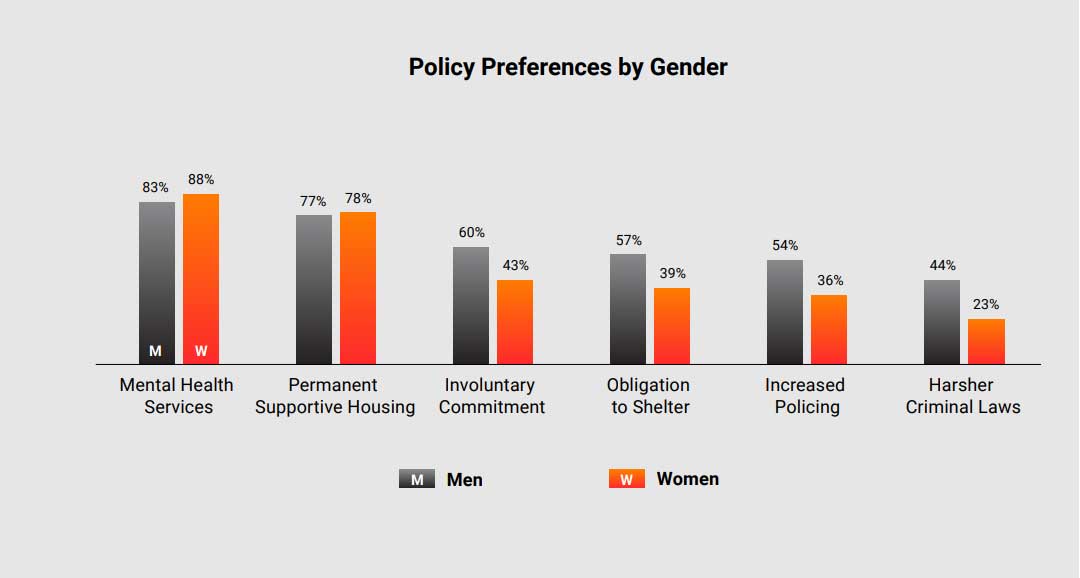

Women are less punitive and more optimistic

Women are more supportive of government action in general, but also expressed feelings of fear and powerlessness. Men are much more supportive of punitive policies focused on criminalization and policing. While there are disagreements, over three-quarters of both groups support permanent supportive housing.

Swipe to View

Women are more likely to believe government should do more on homelessness (73% vs. 62%)

More women than men believe homelessness can be solved (80% vs. 69%).

Women also express feelings of powerlessness (65% vs. 54%) and fear (53% vs. 45%) around homeless people.

QA15: Below are a few policies that local governments might implement to address homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

QA9: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your feelings about homelessness

Addiction perceptions drive backlash

The belief that addiction is the main cause of homelessness is linked to negative attitudes towards homeless housing projects, reducing support for solutions. It also correlates with fear of homeless people, increasing support for policing and criminalization of unhoused people. Pushing back against this misconception is important to keeping the conversation focused on housing solutions.

Compared to those who say financial issues are the top cause of homelessness, people who focus on addiction as a cause are:

MORE LIKELY TO SUPPORT POLICE SWEEPS OF ENCAMPMENTS

MORE OPPOSED TO AFFORDABLE HOUSING IN GENERAL

MORE LIKELY TO WORRY ABOUT HOMELESS PEOPLE CAUSING CRIME

MORE OPPOSED TO HOMELESS HOUSING IN THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD

QA15: Below are a few policies that local governments might implement to address homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

QA9: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your feelings about homelessness

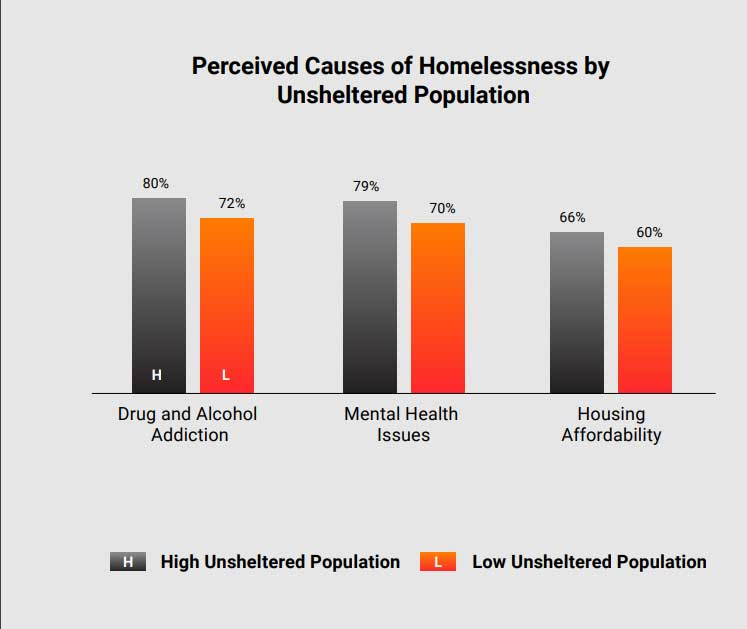

Unsheltered homelessness and negative sentiment

Respondents living in places with higher rates of unsheltered homelessness express more judgmental views of homeless people. When there is a high unsheltered population, the public is more likely to link homelessness to addiction and mental health. They’re also more likely to associate homelessness with danger, crime, and nuisance, suggesting that quality-of-life concerns among housed people are more acute when homelessness is more visible.

QA6: Next, we’re going to show you a series of words or phrases you may or may not associate with homelessness. If you associate that word or phrase with homelessness or homeless people, press “Agree”, otherwise, press “Disagree.”

QA7: Below are a few issues that may cause people to become homeless. Which of the following do you believe are causes of homelessness in your community?

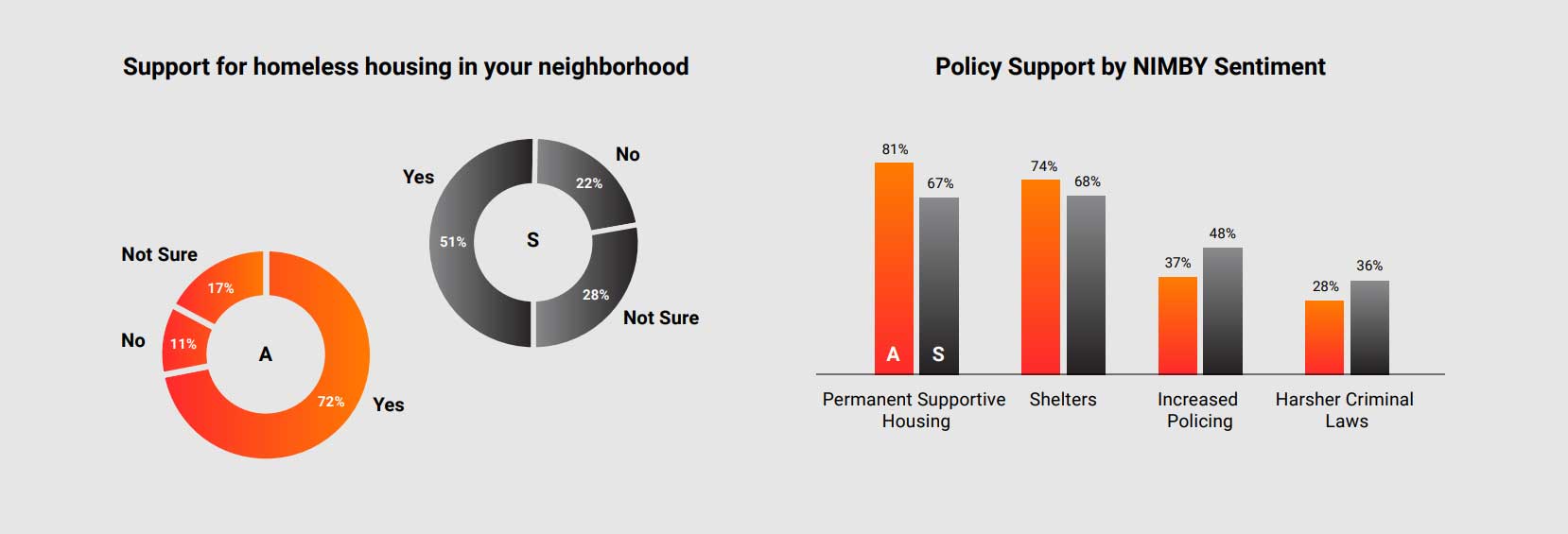

“Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) sentiment drives harsher policy preferences

Those who believe some neighborhoods are better than others for providing shelter and housing are less supportive of housing solutions in general, and more supportive of punitive solutions. NIMBY attitudes represent a major barrier to housing first solutions.

ALL NEIGHBORHOODS should be involved in providing shelter and housing for homeless people.

SOME NEIGHBORHOODS are more appropriate for providing shelter/housing

Swipe to View

QA9: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your feelings about homelessness.

QA17: If there was a plan to build a homeless housing project with on-site services in your neighborhood, would you support or oppose that plan?

QA15: Below are a few policies that local governments might implement to address homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

Identifying Effective

Messages

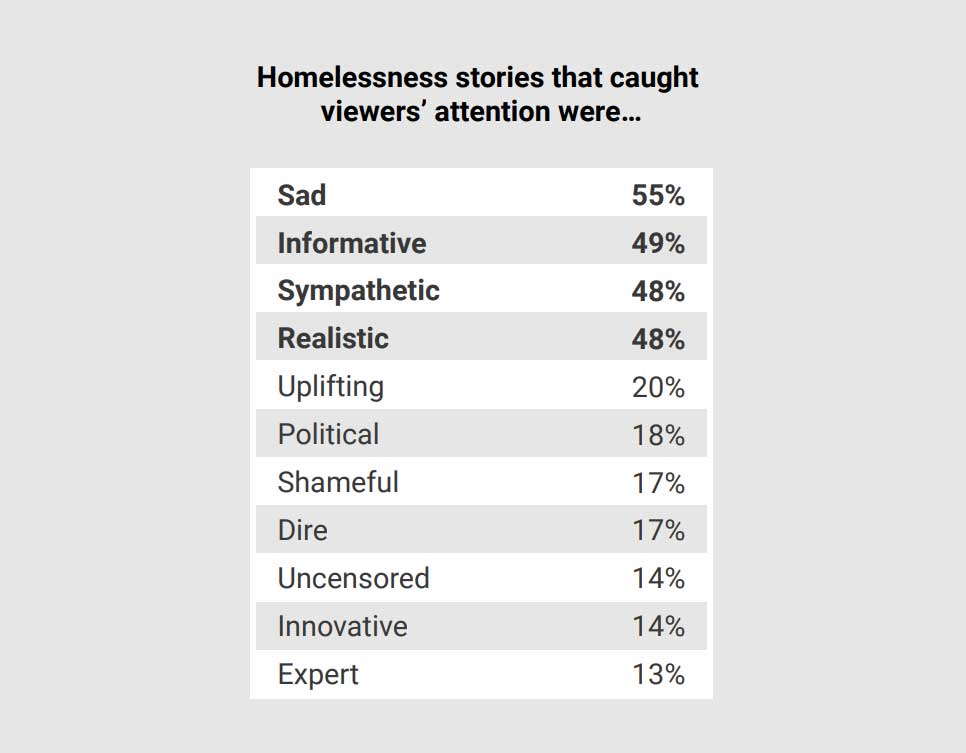

What tone captures the public’s attention?

The most memorable stories about homelessness were emotionally touching but grounded – either sad/sympathetic stories, or informative/realistic stories. This creates an opportunity for storytellers to introduce the housed public to the lives and stories of homeless people in a real and direct way. This makes individuals with lived experience incredibly effective messengers, who can relate to audiences and share a sympathetic story, while also grounding their message in the reality of their experiences.

“Our local newspaper periodically profiles life on the streets and shares stories about people who have become homeless. One recent article described the story of a veteran who struggled with mental and physical health issues which ended up with him being on the streets and alone. The story showed how difficult it is for people without a support system to manage issues that lead to homelessness.”

WOMAN, 53, AUSTIN, TX

QM5: In the past, when stories or videos about homelessness have caught your attention, which of the following best describes those stories/videos?

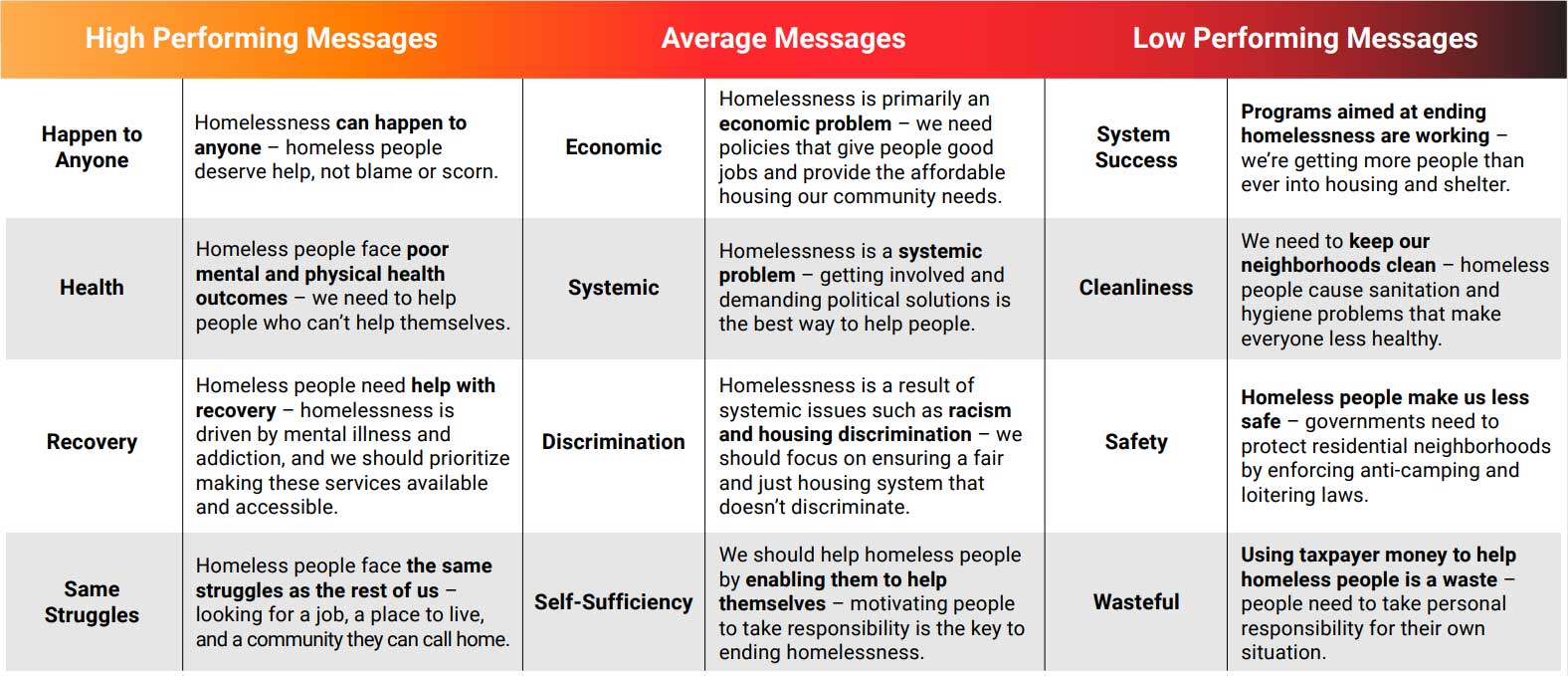

Which messages performed best overall?

The highest performing messages focused on what housed and homeless people have in common, or on issues of health and recovery. In the second tier of messages, the focus is more informative, connecting homelessness to systemic issues of economic and housing justice. Low-performing messages typically focused on problems caused by homeless people themselves. Other low-performing message focused on systemic success, the idea that programs to end homelessness are working.

Swipe to View

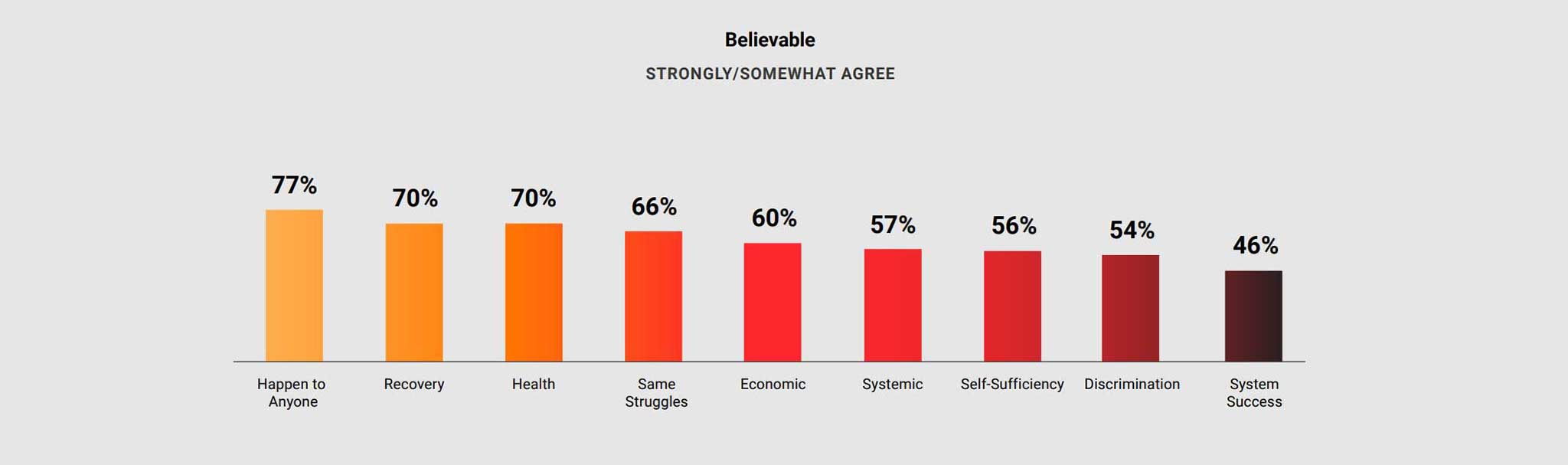

Message believability

Health messages and messages that emphasize the possibility that anyone could be homeless are the most believable, with at least two-thirds agreeing. Messages focused on systemic causes were still believable to the majority of people. If the homelessness sector wants to speak authentically and build credibility, it needs to ground the messages it sends and the stories it tells in the humanity of the people it serves.

Swipe to View

QM6: [MESSAGE STATEMENT]. Keeping the above message in mind, how much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? TOTAL – T2B SUMMARY

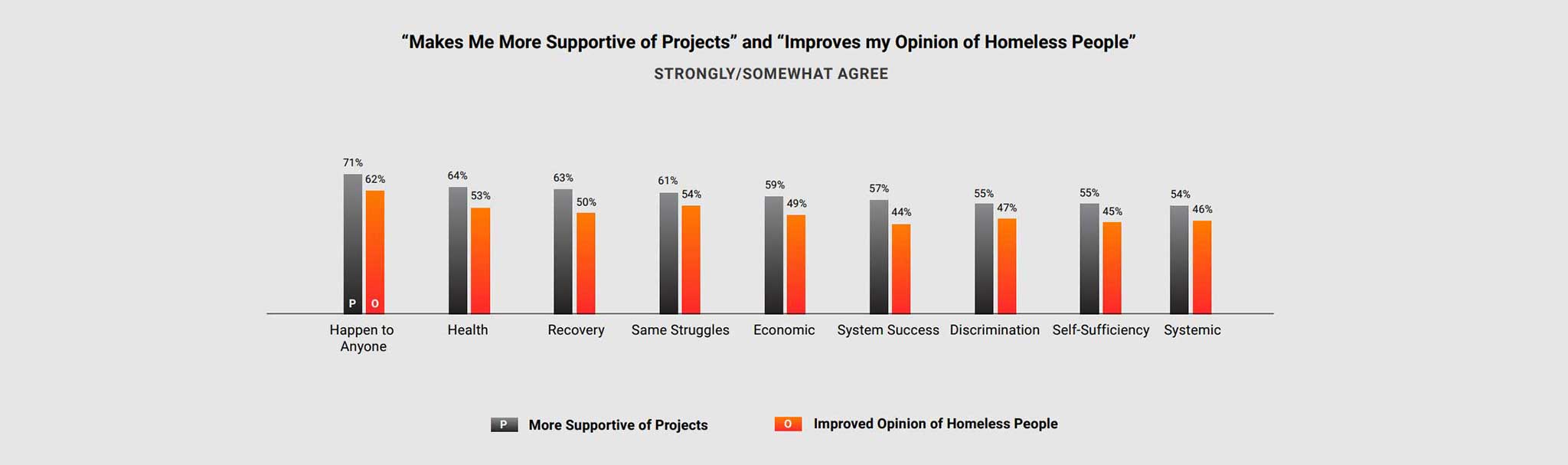

Support for projects and improved opinion of homeless people

The same messages also drove more support for projects and improved opinions of homeless people. While we cannot normalize homelessness,normalizing the idea that homelessness can happen to anyone helps housed people connect to homeless people without coming from a place of blame, scorn, or superiority

Swipe to View

QM6: [MESSAGE STATEMENT]. Keeping the above message in mind, how much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? TOTAL – T2B SUMMARY

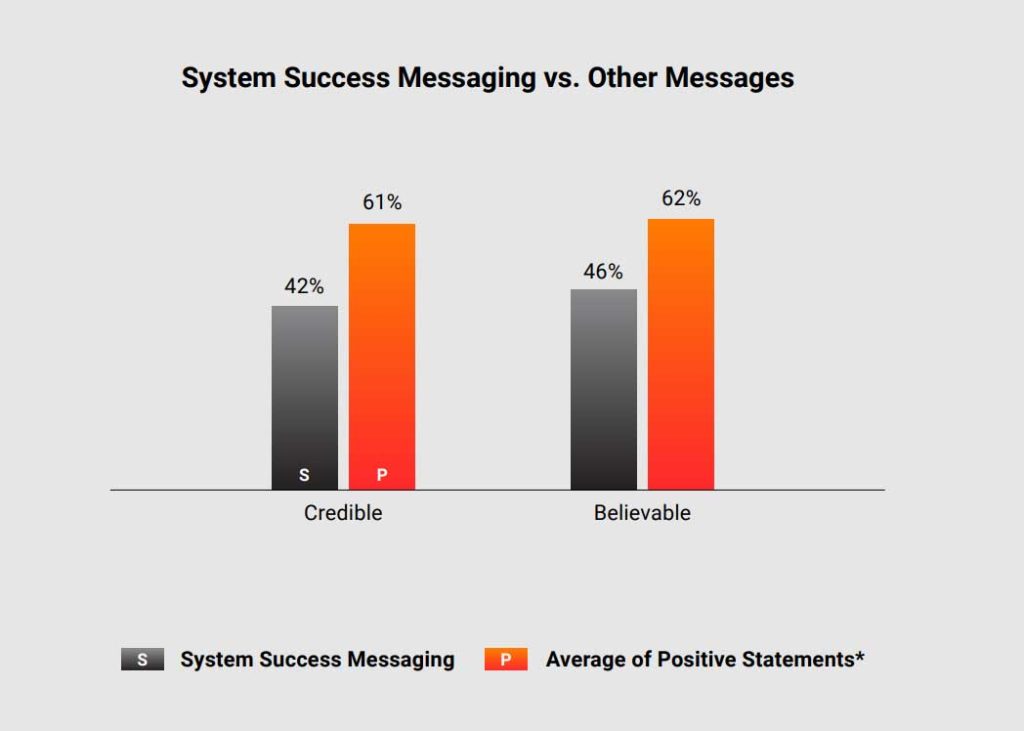

Success messaging has credibility problems

When talking about success stories, our data suggests advocates and providers need to tread carefully. Because the public views homelessness as a growing problem, efforts to portray the homeless services system as a success can lack credibility.

QM6: [MESSAGE STATEMENT]. Keeping the above message in mind, how much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? TOTAL – T2B SUMMARY

*: Average of positive statements excludes “safety” and “wasteful” messages

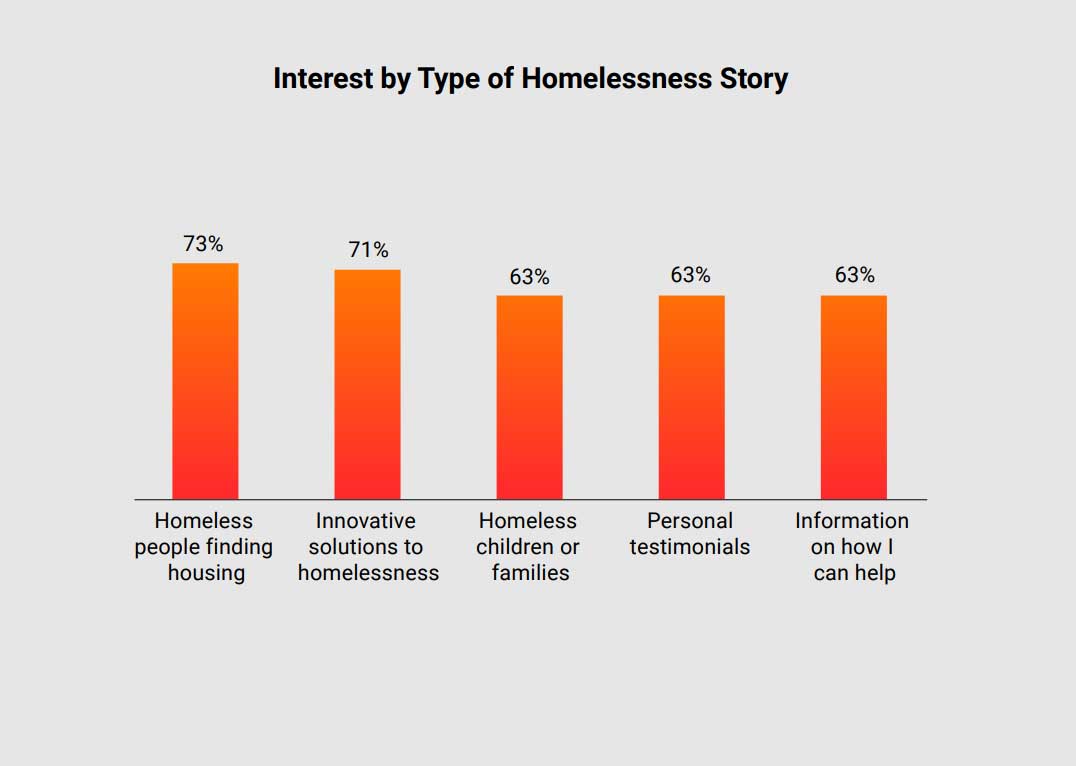

But not all success messaging is the same

In contrast to messages about the success of the system, stories about individual success are very appealing. When telling these stories, explain the challenges people faced accessing services or housing. Personal stories can connect back to systemic issues through examples and calls to action. Don’t portray success as the end of the story, but as an example of how people can help their neighbors by getting involved and demanding more.

QM4: Below are a few different types of stories or videos you might come across about homelessness. How interested are you in each of the following types of story?

Segmenting Audiences by

Homelessness Attitudes

Identifying Audience Segments

Unsurprisingly, conservatives are less enthusiastic about government action on homelessness, though a narrow majority still support government stepping in to help. Those on the left are more lenient towards homeless people using public spaces, feel more guilt when they see homelessness, and are more likely to support homelessness solutions in their own communities.

Segmentation Approach

FACTOR ANALYSIS

Identifies which variables are most impactful.

CLUSTER ANALYSIS

Identifies welldifferentiated segments.

SEGMENT PROFILING

Provides insights into how these different audiences think.

Sympathy and Involvement

Audiences are split by their sympathy for homeless people and their sense of empowerment. Involved Advocates are sympathetic to homeless people and feel empowered to help. While hesitant helpers are also sympathetic, they feel disempowered. Stubborn Skeptics are more opposed to housing and services, but similarly to Advocates they believe they’re able to speak up and make their voices heard on homelessness.

Here to Help

Involved Advocates

“It was an in-depth article that followed the lives of several unhoused people in Los Angeles. It was heartbreaking to read. It made me feel very empathetic to these people. No one deserves to live like that. Housing is a human right.”

WOMAN, 28, LAS VEGAS, NV

Here to Help

Involved Advocates

Involved Advocates

Views on Homelessness

- The group that most empathizes with their homeless neighbors

- Most supportive of housing and homelessness prevention

- Lowest levels of fear/discomfort

- Most opposed to criminalization policies

- Feel empowered to help homeless people

- More likely to be Black

Strategic Recommendations

- Involved Advocates are organic allies who will fight for projects and policies benefiting homeless people.

- They’re willing to connect individual, personal stories with broader system-level issues.

- They want to take productive steps, so give them calls to action.

Soft Supporters

Hesitant Helpers

“I have seen many stories where the homeless person becomes violent or is violent and hurts someone. But that doesn’t mean that I feel that way about all homeless people. Mental illness is a big issue and if the person can get the proper help and medical attention, then maybe it would ease the situation.”

WOMAN, 44, MIAMI, FL

Soft Supporters

Hesitant Helpers

Hesitant Helpers

Views on Homelessness

- Supportive of housing and shelter generally

- Personal hesitance and discomfort about homeless people

- More focused on addiction and mental health

- Still oppose enforcement approaches

- Don't feel empowered to help homeless people

- Most female-skewed group

Strategic Recommendations

- Messages should focus on demystifying homelessness and turning sympathy to empathy.

- Address concerns and fears, but don’t reinforce stigma.

- Connect compassion and education to help them become more informed.

- Tell humanizing stories that they won’t see on the streets or on the local news.

Not My Problem

Active Ignorers

“During local special events, many homeless people are grateful for the help they receive. I know these

are the people that have the ability to think clearly, and are more likely to make better decisions. It gives me a little hope they will be able to help themselves.”

WOMAN, 65, LAS VEGAS, NV

Not My Problem

Active Ignorers

Active Ignorers

Views on Homelessness

- The least interested in engaging with homelessness or homeless people

- Pessimistic about solutions

- Low support for policy responses

- Most focused on addiction and mental health

- Choose to ignore homeless people

Strategic Recommendations

- They are the least supportive of policy solutions, and are generally disengaged.

- Homelessness messages from governments and non-profits are unlikely to reach this group.

- Take a harm reduction approach – avoid creating controversy that pulls them off the sidelines.

Not in My Backyard

Stubborn Skeptics

“Homeless people moved into an area behind someone’s home and within weeks trash, feces, needles from drugs were everywhere. The homeless had begun to harass and even attack some of the neighbors. Crime in the area increased dramatically.”

WOMAN, 49, AUSTIN, TX

Not in My Backyard

Stubborn Skeptics

Stubborn Skeptics

Views on Homelessness

- Strongest negative views about homeless people

- Low support for housing and shelter

- Supportive of a harsher government response

- Least permissive about people living on streets or in cars

- Most fearful about crime and other quality-of-life concerns

- More focused on individual failures than systemic issues.

Strategic Recommendations

- They are the primary opposition to projects and policies.

- Address concerns, but push back against myths.

- Frame projects as realistic solutions, not sympathetic handouts.

- Avoid messages implying that some people are more deserving of help than others.

Recommendations

Our recommendations for speaking

to the public about homelessness

MAKING A HUMAN CONNECTION IS KEY

Emphasizing ways in which housed and homeless people share the same struggles and hopes provides an on-ramp to empathy.

AVOID REINFORCING STIGMA AND MYTHS

Addressing public concerns about addiction and mental illness are important, but too much focus can reinforce misconceptions.

UPLIFT VOICES WITH LIVED EXPERIENCE

People who have experienced or are experiencing homelessness are often the best ambassadors. Don’t just tell people’s stories, support them in speaking for themselves.

BE SPECIFIC

The most memorable stories leave the audience with a specific takeaway about the person or experience described.

WHEN POSSIBLE, MAKE IT INTERACTIVE

The public is often confused about homelessness, so allow space for questions and discussion.

UNDERSTAND YOUR AUDIENCE

Messages need to take the audience into account. Try to identify what preconceptions people bring to a conversation and let that inform your message.

COLLABORATE, DON’T REINVENT THE WHEEL

Homelessness is a systemic problem, and numerous individuals and organizations are working to solve it. Uplift other voices, highlight good examples, and build on the approaches they’re already taking.

GIVE PEOPLE EASY WAYS TO GET INVOLVED

Meeting and talking with someone experiencing homelessness is a fast way to create a moment of empathy. Help people find accessible opportunities to reach out to their unhoused neighbors.

“A homeless woman in Minneapolis was featured. She said just because we're homeless doesn't mean we're bad people. That is the truth.”

WOMAN, 49, MINNEAPOLIS, MN

Methodology, Notes,

and Acknowledgments

Methodology

Audience

- n = 2,520 adults

- Age 18-70

- Registered Voters (proxy for civic engagement)

- Not employed in marketing or social services

- Balanced to census by age & gender

Qualifying Area

HIGH UNSHELTERED

COMMUNITIES

- Atlanta, GA

- Las Vegas, NV/Clark County

- Los Angeles County, CA

- Nashville/Davidson County

- Portland, OR/ Multnomah County

- Sacramento County, CA

- Seattle, WA/King County

- Austin, TX/Travis County

LOW UNSHELTERED

COMMUNITIES

- Boston, MA

- Chicago, IL

- Kansas City, MO & KS/Jackson & Wyandotte Counties

- Minneapolis/Hennepin County

- New York City, NY

- Omaha-Council Bluffs, NE

- Charlotte, NC/ Mecklenburg County

- Miami-Dade County, FL

Methodology

Audience

- n = 2,520 adults

- Age 18-70

- Registered Voters (proxy for civic engagement)

- Not employed in marketing or social services

- Balanced to census by age & gender

Qualifying Area

HIGH UNSHELTERED

COMMUNITIES

- Atlanta, GA

- Las Vegas, NV/Clark County

- Los Angeles County, CA

- Nashville/Davidson County

- Portland, OR/ Multnomah County

- Sacramento County, CA

- Seattle, WA/King County

- Austin, TX/Travis County

LOW UNSHELTERED

COMMUNITIES

- Boston, MA

- Chicago, IL

- Kansas City, MO & KS/Jackson & Wyandotte Counties

- Minneapolis/Hennepin County

- New York City, NY

- Omaha-Council Bluffs, NE

- Charlotte, NC/ Mecklenburg County

- Miami-Dade County, FL

Notes and

Acknowledgments

About Invisible People

We imagine a world where everyone has a place to call home. Each day, we work to fight homelessness by giving it a face while educating individuals about the systemic issues that contribute to its existence. Through storytelling, education, news, and activism, we are changing the narrative on homelessness.

Invisible People is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to educating the public about homelessness through innovative storytelling, news, and advocacy. Since our launch in 2008, Invisible People has become a pioneer and trusted resource for inspiring action and raising awareness in support of advocacy, policy change and thoughtful dialogue around poverty in North America and the United Kingdom.

About the Author

Mike Dickerson is a researcher, writer, and advocate focused on homelessness and local government. Mike is a co-founder and member of Ktown for All, an all-volunteer homelessness advocacy group in Los Angeles.

Advisors

Mark Horvath, Founder of Invisible People

Barbara Poppe, Founder of Barbara Poppe and Associates

Marc Moorghen, Invisible People Board Member

Erin Wisneski, Managing Editor at Invisible People

Alisa Olinova, Founder and Designer at Alisa Olinova Creative

Partners

Invisible People appreciates the assistance and collaboration of our research partners Alter Agents, Opinion Route, and Barbara Poppe and Associates.

Acknowledgments

Invisible People would like to thank Andrae Bailey, Mike Bonin, Ann Elizabeth Christiano, Marc Dones, Marc Eichenbaum, Shayla Favor, Annie C. Neimand, Eric Tars, and Susan Thomas for their feedback on this research.

Notes and

Acknowledgments

About Invisible People

We imagine a world where everyone has a place to call home. Each day, we work to fight homelessness by giving it a face while educating individuals about the systemic issues that contribute to its existence. Through storytelling, education, news, and activism, we are changing the narrative on homelessness.

Invisible People is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit dedicated to educating the public about homelessness through innovative storytelling, news, and advocacy. Since our launch in 2008, Invisible People has become a pioneer and trusted resource for inspiring action and raising awareness in support of advocacy, policy change and thoughtful dialogue around poverty in North America and the United Kingdom.

About the Author

Mike Dickerson is a researcher, writer, and advocate focused on homelessness and local government. Mike is a co-founder and member of Ktown for All, an all-volunteer homelessness advocacy group in Los Angeles.

Advisors

Mark Horvath, Founder of Invisible People

Barbara Poppe, Founder of Barbara Poppe and Associates

Marc Moorghen, Invisible People Board Member

Erin Wisneski, Managing Editor at Invisible People

Alisa Olinova, Founder and Designer at Alisa Olinova Creative

Partners

Invisible People appreciates the assistance and collaboration of our research partners Alter Agents, Opinion Route, and Barbara Poppe and Associates.

Acknowledgments

Invisible People would like to thank Andrae Bailey, Mike Bonin, Ann Elizabeth Christiano, Marc Dones, Marc Eichenbaum, Shayla Favor, Annie C. Neimand, Eric Tars, and Susan Thomas for their feedback on this research.