Editor’s Note: Robert Karron lives in Venice Beach. He enjoys collaborating with the unhoused people in his neighborhood to create statements that attest to the complexities of their lives. Robert started this project to present details of people’s lives that tend not to come across in standard articles. Read more from Robert.

Sometimes people think the high rate of homelessness in Los Angeles is due to our warm weather, which makes it a destination for people who could not live outside in colder climates. However, many unhoused people in our community are from Los Angeles and only find themselves on the street now due to unforeseen circumstances and the lack of affordable housing. This is particularly true for unhoused people over 55, a group that has increased by 20% since 2017. Additionally, an overwhelming majority – 90% of this population – resided in Los Angeles before becoming unhoused.

Below are statements by three people over 50 who live without permanent shelter on the Westside of Los Angeles. These statements, based on interviews conducted over the last two months, are part of an ongoing project to highlight a fundamental idea that seems to get lost in discussions of homelessness:

People living on the street cannot be generalized or stereotyped. Indeed, it’s not particularly useful to talk of “the homeless” at all. Unhoused people are singular individuals with unique histories, opinions, and experiences.

Meet Morgan, a Driver Who Studied Journalism

My name is Morgan, and I’m 55 years old. I’m originally from El Salvador. I immigrated in 1990 with the help of my grandparents and my father. They were already here, and they helped me get a Green Card. I flew to Tijuana, and I crossed the border.

It was exciting because, before then, I didn’t know who my father was. I knew he was my dad—but that’s it. He’d left for the United States when I was young. He lived in Glendale, so I joined him there.

My first job was at a car dealership.

I was looking for work, walking down La Cienega, and I saw a sign—they needed drivers. I drove people back home after they dropped off their cars. I did that for seven years. This was something I’d also done in El Salvador. I’ve always been working on cars—driving them or fixing them. Small cars or 18-wheelers, I can do it all.

I immigrated here after the civil war in El Salvador ended. I was in the war. You had two choices: go to the Rebels or the government. I was active for three years, and I made bombs, and then I gave them to somebody. I don’t know what happened to them — I have some idea, but not really.

My mind was thinking differently at that time. I had to fight for my people and my country. Eventually, though, I realized it was all a big drama—for the United States and Russia, just a war between them. We acted it out.

Before the war started, I was in college. I’d completed more than three years and was about to get my degree. But when the war started, the government shut down all the schools. What was I studying? You’ll laugh—news reporting.

After I left the car dealership, I drove a truck to a flower shop.

That was another seven years. Then something bad happened. I went to prison—for almost ten years. I was driving with my girlfriend, and she wasn’t wearing her seatbelt. We got in an accident, and she was killed.

I hadn’t been drinking that day—but the day before, I had been, and it was in my system. I was convicted of manslaughter.

At first, I was so depressed I wanted to kill myself—not because of the prison sentence, but because I loved her. She was the woman I loved.

These people put me in prison because that thing happened, but I didn’t mean to do it. It was an accident. Somebody ran the red light in front of me. I was incarcerated in the High Desert, close to Colorado. I continued my education there—I got my GED (which I’d already got in El Salvador, but not here). I also got a certificate to be a Teacher’s Aid.

By the time I got out of prison, I’d lost my grandparents and my father. I didn’t have anywhere to go. An old girlfriend took me in for a while, and I got a job washing dishes at a Mexican restaurant in Venice. But soon after that girlfriend had to go back to Ecuador because her grandson was sick. I turned to cocaine to feel better, to kill the pain.

In prison, you’re not able to cry. If you cry, you’re weak. So I had to keep it inside that whole time. When I got out, and my one connection here left the country, I had to release it. I’ve been on the street since then.

How did I get through the recent rainstorms?

I put my tent in a high place, and I put an extra tarp over it. I stayed dry. I like to keep myself dry and clean. I have two tents for that reason. I live in one and use the other as my “shower.” Sometimes, if it’s too cold, I’ll heat the water with my stove. I make it work.

There’s a lot I want to change, a lot I want to do. I write it all down in my notebook. Want to see what I’ve written down? I’ll show you my list:

- No more drugs.

- Get a place to live.

- Get a motorcycle.

If I find a place to live, I think I’ll be able to be on my own within a year. I really do. Maybe even six months. I can do more than work on cars. I could be a handyman—help with plumbing, hanging drywall, and painting. But it’s not going to happen overnight. I know that. Everything is a process. But I have to try. If I don’t try, how will I do it? I can’t stop trying.

If I get a place, I’ll have an address, so I can go to the DMV and get an ID. I could get my Social Security card and apply for Social Security. I need help. In that car accident, I injured my arms, hands, and back.

Some people who live across the street give me a hard time for being here. I understand that. But they don’t understand something—I don’t want to be here. I’d rather be somewhere else.

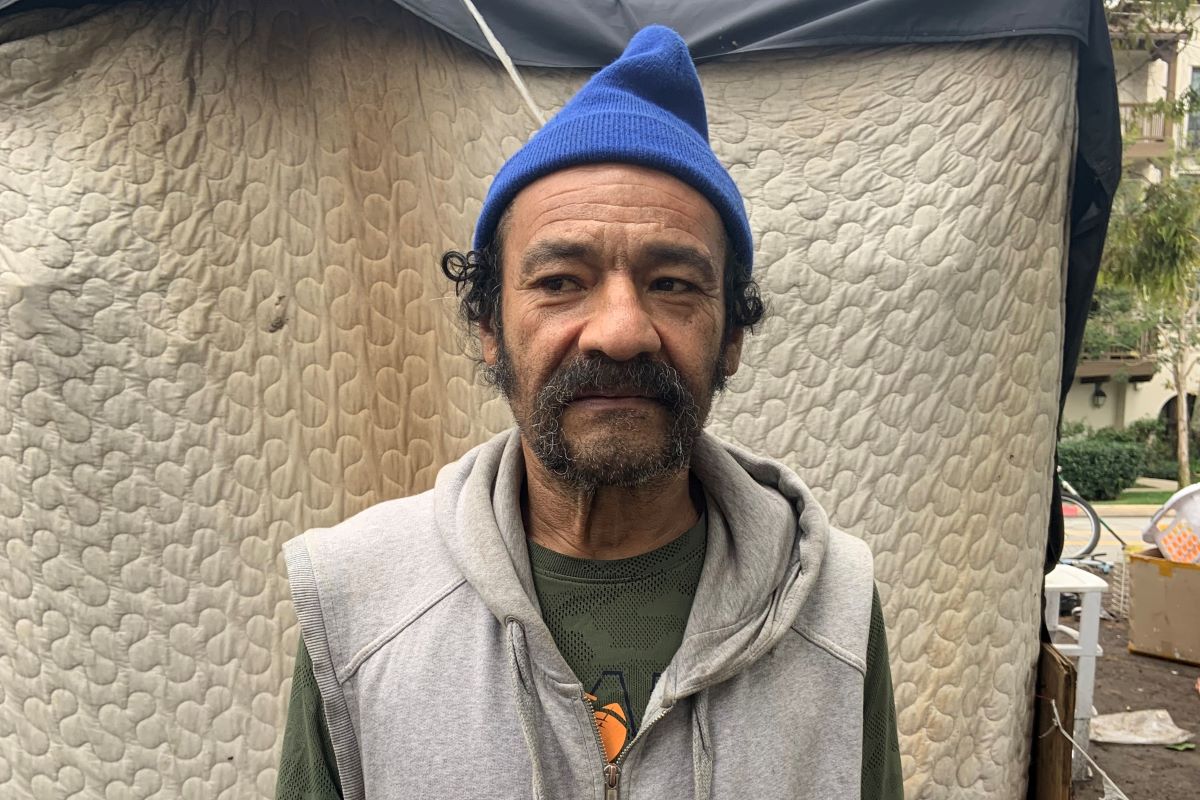

Meet Rodrick, Former Small Business Owner

My name is Rodrick, and I’m 53 years old. I grew up in Granada Hills, in the Valley, and I went to Birmingham High School in Reseda. Eventually, we were living in Woodland Hills.

I have a brother, but he’s 11 years younger than me. The school was boring. I have ADHD. Also, I had different ways of doing things, and the teachers never liked it. They’d tell me it was wrong.

In math, I’d find the solution with fractions, but when I’d show my teacher, she had a problem with it. It wasn’t her way. They wanted me to push a button, and I wouldn’t.

I didn’t write many papers, but I wrote my own stories — Sci-Fi—off-world stuff. One was about an alien planet behind the sun that crashed into Earth, and when the aliens jumped out, they used the fractals on their heads to create a wormhole that let them jettison from planet to planet.

I’m in my head a lot of the time. When I was younger, when my mom punished me, she’d take everything away. It stimulated my mind. I would build worlds. Still do.

After high school, I spent a lot of time changing diapers. My girlfriend had three kids, back-to-back. It wasn’t a good relationship—there was violence. One day we were all together, having dinner, and my kids felt the energy in the room change, and they took their food upstairs. They were preparing for this violent confrontation they’d seen before. I looked at them and thought I don’t want that for my kids. I had to leave.

I haven’t been in touch with them or their mom for 20 years. Soon after, I married someone else, but that wasn’t good, either (I jumped out of the frying pan and into the fire). I had a kid with her, too. So—I have four kids: two girls and two boys. The oldest is 27.

Those relationships failed because of me. There was something about me that attracted that type of relationship. I did it once; then, I did it again. So there I was. When the second one failed, I was faced with myself. I think something inside me wasn’t dealt with. I grew up with arguing and violence, and I didn’t realize—that gets transferred.

My mom kicked me out of the house when I was 17. But for a while, things were going well. I worked for Kaiser as a driver, making $18 an hour. But this whole time, I kept thinking things weren’t right. Something was wrong with the world, with me. I kept thinking: It’s all for nothing. It’s going to come to an end. My perception of life is bleak. Sometimes I wonder if I self-perpetuated that. Your thoughts have weight, so they exist.

It’s like I created my own universe—because this, being unhoused, is exactly what I feared.

I quit the Kaiser job to go into finance. At first, I was a “skip-tracer,” locating assets for people who owed money. It involves deception. You call the person’s associates, who tell you everything because they don’t like the person.

The company moved to San Diego, so I moved with them. I was impressed with the moving company. I saw how much money they made in a weekend with one truck. And all in cash. I started working for the guy who moved me and asked to be trained. I learned all the paperwork, and soon I was driving for myself. I’d get help from guys I’d find at Home Depot.

When I moved people, I’d put my magnet on their refrigerator; that’s how I drummed up my business. Back in the day, there was just the phone book. I had to come up with a name. I wanted my name to be at the front of the book, with the “A” s. I called it At Your Door, Moving, and Storage.

When guys don’t show up, you have to do it all yourself because it’s your reputation. Some jobs took me two days—by myself. But it was a good business, and I liked it. When you do something for someone they don’t want to, you get something out of it. To build something up like that and then to have it taken away – that’s hard. I lost the business in my divorce. I hadn’t paid my taxes, and my ex-wife reported me. I lost it all.

I don’t blame my ex-wife. I should have paid my taxes. It’s my fault. I was wrong. My decisions put me here. That was ten years ago—but it feels like yesterday.

I’ve been on the street for ten years but not in the same place.

I’ve been in this spot for two months. I have friends—across the street, down the street, down another street. We do a rotation so that when cops tell us to move, we have different spots to go. I’m under a freeway overpass now, but when the rains came, I wasn’t. That was hard. My tent got flooded.

What would it take to get me out of my situation? Me. Nothing can get me out of the loop but myself. Even if they took me out of the loop, I’d jump back in. Yes, I sound logical, I sound rational—but, at the end of the day, there’s still something inside me that’s so frightened of everything. A little kid. He’s at the helm. He’s driving.

It seems like I’d make the wrong move—just to make the wrong move. I don’t want to fail, but then I fail on purpose, so I don’t fail. Understand?

People who move from where I am to having an apartment and a job—it’s like something turns on, in their psyche, not in their thinking, but in their core. They decide—nothing else will get me to be that way anymore. This right here is a way of life.

Am I close to having that switch turned on? Yes, it’s always right there because it’s hard out here; it’s a struggle. This is hardcore.

Nobody wants to say they’re a failure. But it’s also hard to stop.

I have to take the steering wheel back from the little kid who’s driving—but it’s hard because he’s a part of me. I’ve got to grow up, that’s all. I have to reach out and flip the switch myself. How would that happen? I think I’d have to hammer out a plan, and then I’d have to stick with it. I’d have to check in with somebody and maybe get a reward for each step. I know that sounds crazy and babyish, but I’m broken. I am a broke person.

I want to find solace: some freedom and peace. I’d have to be out of this situation to start thinking like that. Right now, I’m in survival mode. So, yes, it’s up to me—but to flip the switch, I’d need to find a place to live first. To get out of survival mode. Right now, I’m trapped—in myself. With a place to live, I’d be on the outside, looking in.

Meet Kelly, a Caretaker for the Elderly

My name is Kelly, and I’m 55 years old. I grew up around here, in Mar Vista, and I went to Mark Twain Junior High School. I was enrolled at Venice High School—but I never went. It was scary. Too big for me—there were too many people.

Instead of going to school, I took care of my grandmother. She was a nurse, and she was nice to me. She had 16 children! She wanted me to go to school, but I’d hide in her attic. Sometimes she’d hear me up there—”I hear you! Go to school!” But I never went. I just sneaked in and out of the attic until it was time for dinner.

I can read and write all right, but math—no way. I can’t do any of that. I lived with her until she passed away in 2000. Then I took care of my mother until she passed away in 2007. I’m a caretaker, yes. That’s what I do.

In 2007, I moved in with my boyfriend, Mark—into his house on Walgrove, also in Mar Vista, and I started caring for his mother. We lived there for 14 years. I’m still with him—we’ve been together for 26 years; I met him when I was 16.

See, I’ve been spoiled all my life. I lived with my grandmother and then with my mother. And I’ve been with Mark this whole time. And Mark lived with his family, too, in the house we moved into.

But we don’t live in that house anymore. A few things happened.

First, I accidentally set the house on fire. Thanksgiving Day, three years ago. I turned on a space heater in the bedroom and walked away. I must have dragged the bed sheet behind me because when I went into the den and looked out the window, I saw flames coming from the bedroom window.

The fire destroyed a lot. They were going to remodel the house with the insurance money, but COVID started, which stopped the remodeling.

The house was unlivable for Mark’s mother (she’s 93) — so the family had to put her into an assisted living facility in Tarzana. It’s a nice place — two other senior citizens live there with her, and they’re well taken care of — they didn’t catch COVID! The staff really took care of them.

That facility costs Mark’s family $8,000 a month. To make that amount, they rent the house out—the one we were going to remodel—and Mark and I live here, on the street.

We used to sleep in this RV, but people tried to steal Mark’s truck — three times now. So now we sleep in the truck. The last time they tried to steal it, we were inside of it! The only reason they didn’t steal it is that we were in there.

I’ve never lived like this before, ever.

It’s lucky, in a way. Imagine if Mark’s family didn’t own the house! They wouldn’t be able to rent it out, then they wouldn’t be able to afford the assisted living facility. His mother might be on the street, too. Thank God they have that investment.

I’ve applied for Section 8 housing—I was on their list for 11 years. I don’t know anything about computers or how to work them, though. They said they gave my spot away because they had no way to contact me. They put me at the front of the list again, from 2,500 people all the way to the top. But when I tried to call them, nothing happened. Anyway, that was a while ago.

These days, I’m working with LAHSA to get housing. LAHSA took me to the Social Security and General Relief offices. They were really nice to me. We’ll see what happens.

I have two sisters and one brother. My brother is in La Verne, and he manages a mobile home park. My sister is in Las Vegas. She has health issues; she just had surgery on her neck. I also have a daughter who’s 35. She has three kids and lives around here, in Mar Vista, too.

My siblings can’t take me in, and my daughter would, but she’s already taken in her husband’s mom, so she doesn’t have room for me. She’s so busy with those kids and her mother-in-law; she never stops moving. I don’t want to be a burden on her. She comes here twice a week with groceries for me. She’s wonderful. I’m truly blessed.

What do I do all day? I clean the streets—right out there. I use a rake. People around here are horrible. They haul in stuff all the time, and they leave it out all over the place. I’m constantly trying to clean up after them. I’ve already cleaned this street once today, and I’m going to clean it again later. Do I know these people? Not really. I try to keep to myself. It’s just me and Mark.