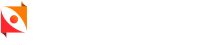

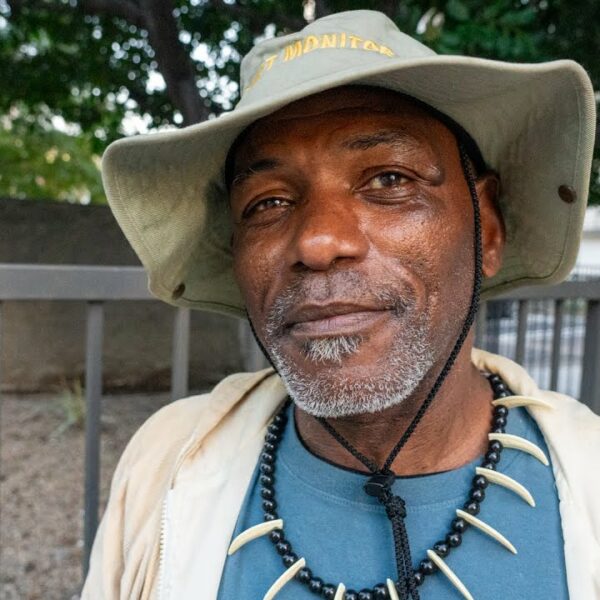

Meet Betty. Betty is a person I know from stories, statistics, and political debate. Actually, there are a lot of Bettys. In my time working with integrated healthcare teams (those who provide wraparound services to patients with multiple conditions and poverty) practically everyone I spoke with had a Betty or two to tell me about.

Betty is homeless, but that’s not her only problem. Let’s be honest, society wouldn’t talk about Betty if she were “just” homeless. Betty is different. Betty is expensive. She went to the emergency room 38 times last month, in Trenton or Portland or Chicago or Austin or Oakland or the VA hospital. How is that possible, you might ask. Betty is what they call a “frequent flyer.” Because she is indigent, her medical bills go to the taxpayers. Betty cost the taxpayers six figures in two months last year.

Taxpayers and politicians judge Betty, and the hospital, and the clinics. Why does she cost so much? Maybe she gets brought in by ambulance because somebody finds her passed out drunk or high somewhere. Perhaps Betty is taking advantage of the system because the ER is warmer than outside. Maybe being in the ER is easier than working.

Actual Facts about Betty

- Betty has diabetes, and needs to take medicine constantly. The medicine has to be refrigerated and hygienically injected, so she doesn’t get an infection.

- Betty is bipolar. She doesn’t have the right medicines for that. The right medicines would make her diabetes worse and require complex management.

- Betty doesn’t have enough to eat, which means Betty’s blood sugar is erratic.

- Betty has very bad Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. She was abused, a lot, and has been poor her whole life.

- Betty’s diabetes took part of her leg. She can’t get around very well. Everything she owns is in a shopping cart.

- Betty hates the Emergency Room. She is often found nearly dead from blood sugar problems, and brought in by ambulance against her will.

- Betty has been on every housing wait list in the state for years. Nobody wants to take Betty into housing because she won’t go through the shelter system first.

- Betty has tried to go to the shelters, but they aren’t safe. Her medicine kept getting stolen. The last time Betty was in the shelter, she was attacked.

- Betty has never had any steady mental health treatment.

Betty’s Medical Access: What’s Going Wrong?

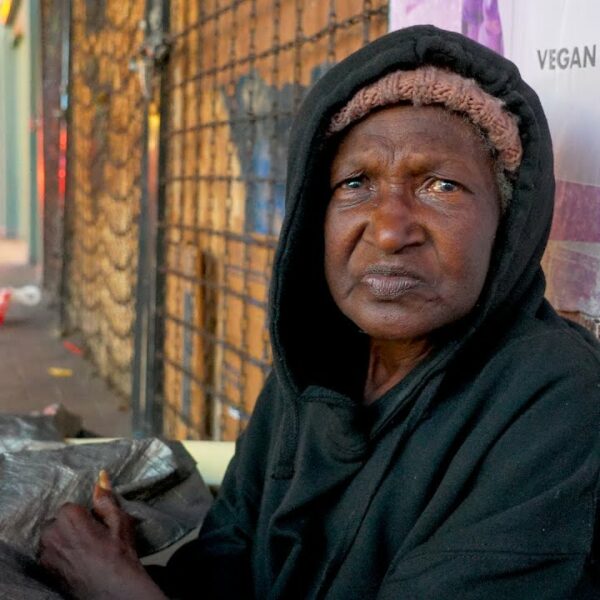

The ER staff don’t know what to do with Betty. She makes them cranky. They secretly think that maybe Betty just wants drugs. They don’t give her any. “Treat ’em and street ’em” (actual quote) is their directive. This is typical ER shorthand in public hospitals. There’s no staff or time or money to “solve” Betty.

Nobody else within medicine wants to deal with Betty either. She’s tried the local clinic, but there’s so much turnover there. Waits are long. When she finally talks to a doctor, they tell her she has to find a way to refrigerate her meds and she has to stop “losing” them. They have a word for Betty. She’s “noncompliant.”

Two of the three doctors have told the front desk never to put Betty on their schedule again. The nurse practitioner, fresh out of school hasn’t met her. And she only gets 15 minutes per patient anyway. She’s fresh out of school and can’t solve years of medical neglect in 15 minutes. She’s already job searching.

Betty thinks she’s going to die soon. She might be right. The average age of death for the chronically homeless is 50, their lifespans radically shortened compared to the general population.

How to ‘Fix’ Betty

In all of the places I’ve visited where Betty has received real help, the staff repeated one theme: stop thinking of Betty as a problem to be solved, and start thinking of her as a person. Betty’s biggest needs are tied between housing and people who care about her. She needs time to trust them. She needs to be part of decisions about her own care. Betty needs immediate and intricate support, helping her access food and medicine on a regular schedule. She needs people to stop telling her what to do and be patient enough to work with her to find strategies to manage her diseases.

Obviously, Betty needs housing. That much is obvious. It needs to have a refrigerator. Betty needs to feel safe in her housing. Betty probably needs some mental health treatment, and she definitely needs a good, consistent primary care doctor. She also needs a psychiatrist who can help her with her bipolar medications. And she needs the people who are taking care of her to talk to each other.

The reality is that programs that do this work are few. They all struggle with turnover from low pay, lack of funding, and the burnout of grinding, emotionally difficult work. Programs that could succeed with Betty are even fewer.

When they work, though, infuriatingly, these programs save money. Even a high-end luxury apartment and complete wraparound care provision costs less than “renting” an ER bed for most of the month. And it offers the chance that Betty not only recovers, but thrives, reconnects with her family, finds a job and a support network.

Being Killed by Intent or Neglect

Of course, the chances are high that she won’t, too. Many Bettys will fall prey to the current homeless mortality statistics and the years of national failure to build housing and protect the poor. But as one doctor who specializes in treating homeless patients told me, “Wouldn’t you rather have people die knowing they were loved? Isn’t that better than being killed—by intent or neglect—in the streets?”

In the end, these are the decisions we have to face, and we have to face them ever more frequently as baby boomers age. Cost isn’t how we make them now, so let’s stop pretending this is about taxpayer money. Instead, let’s ask what it takes for Betty to actually matter, to all of us, as a part of American society.

That’s the goal.