Seven Reasons Social Workers Use Euphemisms for PTSD

In “frontline” community work, we’ve got a lot of words to describe a very similar phenomenon: secondary trauma, vicarious trauma, burnout, compassion fatigue. They don’t have quite the same birthplaces or implications, but frontline workers use them pretty interchangeably. We are trying to describe the emotional, physical and mental toll that being exposed to human suffering and oppressive systems can cause.

What I’ve noticed is we use these terms even when describing what are really major primary traumas and tragic losses. Sometimes, it’s just people being imprecise, but I think our PTSD and grief get minimized and overlooked. There’s a way in which we are not allowed to truly own our experiences as traumatic or as profound grief.

I’ve been working in community education with homeless youth for over a decade. In homelessness, both helpers and helpees are sitting in the middle of a chaotic intersection of social crises. Lately the most overwhelming crises have been overdose, housing and mental illness, but there are many more. It’s a multi-vehicle pileup, for sure.

Vicarious trauma, if you find the concept useful, comes from working with suffering in a secondary way.

For example, hearing stories of childhood abuse causes pain. PTSD is caused by anticipating, experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event. Some of the real-life terrifying events that occurred in my workplace were fights and stabbings, overdoses, seizures, an axe-wielding teen on meth, graphic threats, a girl swallowing sharp objects, a staff member thrown over a desk.

There is a constant potential for danger and crisis in a shelter. When workers are more activated and fearful after an event, it’s not just because our limbic system is still activated; it’s because we fear it happening again. And it will happen again, it’s just a matter of when. Sometimes an overdose happens before the adrenalin has subsided from a previous overdose response.

We are in constant fear of the deaths of our clients. They’re great, but they take risks to cope.

Imagine working in the home of over 30 traumatized young people with nowhere else to go, and the mental illnesses, criminal behaviours, chaotic substance use, suicidality, and self-harming that comes with that. The violence young people enact on themselves, each other, and workers is very difficult to process.

It’s clear to me that these experiences have caused PTSD, but I have been much more likely to use the term, “burnout.” I went back to my own rant article, “Self-care should not be a second job,” to delete the work “vicarious” because I was actually referring to all kinds of traumas that happen at work.

The reasons we do this, I think, are complex and layered.

1) Stigma on mental illness.

Just because we have training and have worked with people with mental health struggles for years doesn’t mean we are immune to stigma.

2) The literature on worker PTSD is not focused on shelter and drop-in workers.

It mostly focuses on therapists, who mostly experience secondary trauma. Or, it focuses on first responders like paramedics, police, and ER workers. Shelter and drop-in workers have to try to fit the frameworks from that research into their own realities, when perhaps what we need is a language for the daily mix of primary and secondary trauma we endure while — serving people we like, root for and feel responsible for.

The reason that there is a gap in this research is indicative of the lack of social validation of helping work done with marginalized people. Shelter workers are first responders and counsellors, but they are not recognized or compensated for their very stretched skills.

3) The professional helper/client binary.

They have PTSD; we’re the social workers paid to help them. Perhaps we don’t admit to our PTSD because we worry it would mean we don’t have the right to help them. We trained for this; we signed up — we’re supposed to already have the character and skills to manage these sad and scary events, right?

4) Having good boundaries and coping strategies is easier said than done.

We are taught that part of being a professional is having good boundaries, leaving work at work, and practicing self-care. But I think the way we try to achieve these boundaries is often unhealthy – we just squish the feelings down and go about our life. Misnaming the impact of trauma is a way of doing that squishing.

5) Guilt about the privilege we have in relation to our clients, particularly if they are very vulnerable.

Some of us believe, at some level, that our fear and grief don’t matter because we can go home. We were compensated (poorly) for the stress; our clients were there for that critical incident too and they’re not getting any compensation.

6) Minimizing the severity and impact of the incident.

It’s common for social workers to say to ourselves things like, “Well, no-one was actually hurt that time we had to lock ourselves in the office” or “I intervened in that attack; I wasn’t attacked myself,” “Or, everything’s fine; we stopped the bleeding.” Our managers too often minimize these incidents, too — when they don’t follow up after an incident, it’s a tacit message that it wasn’t that big of a deal.

7) We believe we don’t have the right to fear and grieve their losses because we were paid workers, not friends or family.

Sure, the relationship is different, but there is — BI nothing secondary or vicarious about the loss of a client. These are meaningful relationships that sometimes last many years. We may spend a lot of time with them, we may have to watch their decline and not be able to stop it. And we might imagine a whole different, easier life laid out in front of them. It’s tough that those futures we imagine will not happen.

When we’re not calling the impact of our experiences PTSD, we likely can’t properly heal from PTSD.

Let’s say “PTSD” and “grief” and “workplace trauma” when that’s what we mean. And while we’re at it, let’s not use the phrase “compassion fatigue.” Compassion is an energizing and bottomless resource. We are fatigued by fear, loss, violence, and oppression. To fight that fatigue, we should be advocating for systemic interventions and supports, and we should be seeking treatment. We should be sitting with the grief, fear and pain. And we should acknowledge that helpers and helpees are all in this mess together.

After the loss of a youth leader, I cried uncontrollably.

I took the next day off and doggedly mowed my lawn and pruned bushes and scrubbed my house until I was dripping with sweat. While wrestling with unruly bushes, I wrestled with my guilt – guilt that I hadn’t been able to prevent her death, and guilt that I was so upset. I remember thinking I felt devastated, and realizing there must be no word big enough to describe what her mom felt. After crying and sweating to exhaustion, I realized I was allowed to grieve, and that it was normal to be afraid of the next time it would happen. I thought, ”We are paid to take care of clients, not to care about them.” That I did on my own. That was real.

In fact, the genuine care I had for this young person is actually quite likely the best thing I did for her.

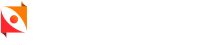

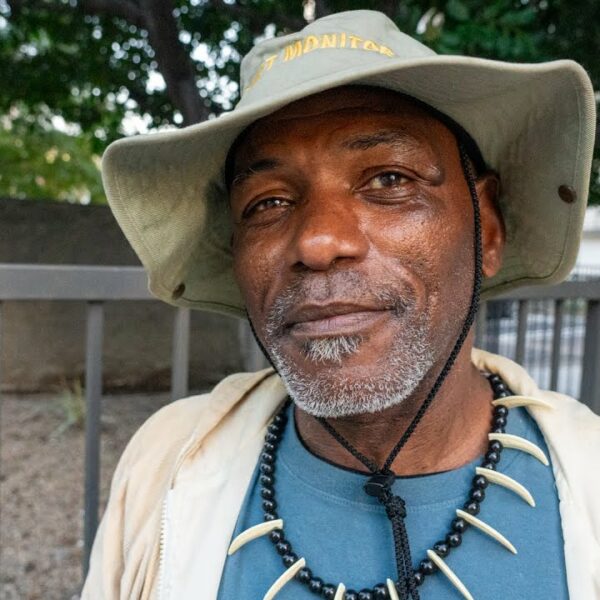

Photo by Claudia Wolff on Unsplash