Tips for Journalists to Improve Reporting on Homelessness

Nearly half of Americans are afraid of people experiencing homelessness. About 35 percent of those surveyed agree with the forcible removal of people from encampments and other unsheltered spaces. In comparison, 45 percent said, “some neighborhoods are more suitable for shelters than others”—in other words, not their neighborhoods. And 47 percent of people surveyed believe people experiencing homelessness will cause crime in their neighborhoods, even though unsheltered homeless people are more likely to be victims of crime.

These misguided opinions are informed by a media narrative that paints people experiencing homelessness as addicted to drugs, mentally ill, and victims of their own choices. That narrative implies homelessness is a result of personal shortcomings, not a systemic failure.

John Oliver lambasted this narrative in an episode of “Last Week Tonight” last October, using clips from news programs and talk shows to illustrate how people experiencing homelessness are portrayed.

“Far too often, stories focusing on homelessness are presented solely through the lens of how it affects those with homes when in reality, it’s obviously the people without them who need the real help,” Oliver said. “The story of homelessness in this country is grounded in a failure of perception, compounded by failures of policy.”

Oliver blamed Ronald Reagan for pushing the notion that homelessness specifically and poverty in general is anything but a public policy choice.

“Reagan… came to power at a time when homelessness was increasing, and made the problem far worse by cutting programs for the poor and slashing housing subsidies by 75 percent,” Oliver said.

The former president then pushed the idea that homeless people chose their plight.

“One problem that we’ve had even in the best of times, and that is the people who are sleeping on the grates,” Reagan said. “The homeless who are homeless, you might say, by choice.”

How the Media Wrongfully Reports on Homelessness

The media then reinforces these misperceptions. The Center for Media and Social Impact reviewed television episodes and news articles from 2017 and 2018, looking for mentions of housing-related topics. Researchers found the following:

In the most watched TV shows:

- Homelessness was characterized as being the same across the country. Those who experience homelessness were largely portrayed as living on the street, and the stories pointed to the cause of homelessness as a personal choice or moral failing (drug use, criminal behavior, mental illness). Episodes rarely examined systemic causes of homelessness.

- More than 80 percent of homeless characters only appeared in one episode. More than half had less than ten speaking lines, and nearly half didn’t speak at all.

- Solutions to homelessness were oversimplified: they either called on the homeless individuals themselves to correct their behavior (stop committing crimes, get treatment for their addiction, get a job) or donate to charity.

In “topic-based” shows that deal directly with housing issues and gentrification:

- Homelessness was portrayed “at a local level through (transformative) narratives of civic imagination.”

- The cause of homelessness was portrayed as societal/systemic 67 percent of the time.

- Homeless characters appeared in multiple episodes and had multiple lines per episode.

In the 12 most-read newspapers in the country:

- Issues surrounding homelessness and housing stability received less than 0.002 percent of news coverage in 2018.

- “Homeless” as a keyword is just as likely to be mentioned once in an article on another topic as it is to be used in a substantive article on the issue.

- Almost 90 percent of articles about homelessness failed to address the connections between homelessness, affordable housing, and gentrification.

We Need Better Reporting on Topics of Homelessness

Clearly, the media narrative surrounding homelessness needs to be rewritten.

In 2016, the Renaissance Journalism Center and the Community and Media Lab at San Francisco State University held a briefing on homelessness. Afterward, San Francisco Public Press writers Hye-Jin Kim and Meka Boyle offered tips for local reporters on how to better write about homelessness and housing.

Using that list and our own experience, we’ve composed our own guide for journalists:

First and foremost, recognize the diverse causes of homelessness.

The most prevalent—always—is lack of affordable housing, a problem that continues to grow in the wake of the pandemic as house prices soar amid limited housing stock. But domestic violence and familial conflicts may also drive people into the streets. Some people may literally have to choose between housing and survival.

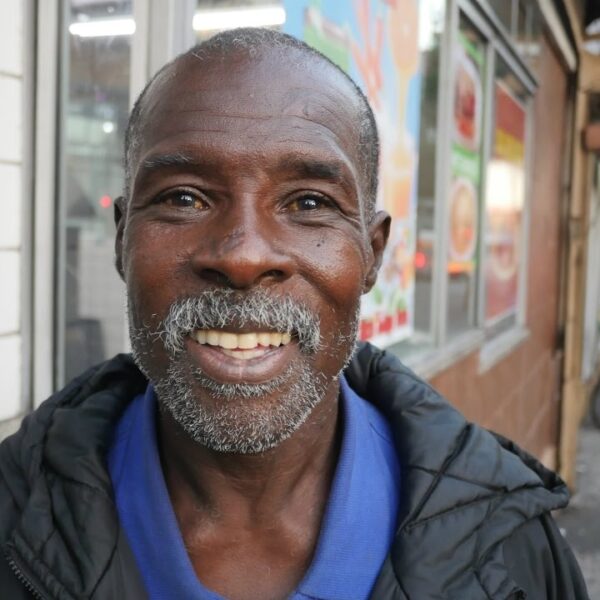

Don’t stereotype people experiencing homelessness.

This seems obvious, but every circumstance is different. While some people are living in their cars, others are couch-surfing or staying in shelters.

Highlight the “invisible” homeless people.

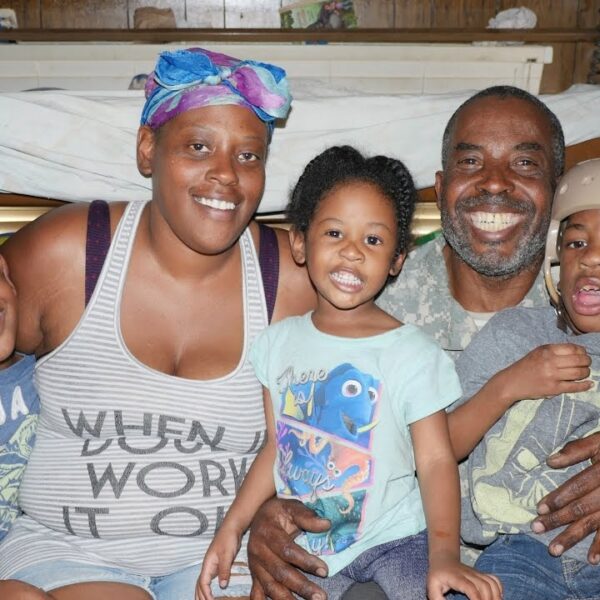

Many people experiencing homelessness are ignored by the mainstream narrative, which focuses on middle-aged single men. But families make up about 30 percent of the homeless population. Young adults who identify as LGBTQ are at much higher risk for homelessness than their non-LGBTQ counterparts.

Identify the historical context around homelessness.

Homelessness as we know it today would not exist without several important events:

- Cuts to public housing funding and welfare during the Carter and Reagan administrations

- The closure of state mental institutions and the end of the Vietnam War

- The Great Recession and housing crisis of 2008-09

- Now the current housing crisis

And you can’t discuss modern-day homelessness without addressing the systemic racism that pervades American society, from redlining and exclusionary zoning to intergenerational poverty to housing discrimination to the War on Drugs.

Examine criminalization policies.

What’s really being criminalized? Are people being punished for creating public health hazards or a public nuisance or for sitting down? When encampments are cleared, what happens to the people who are moved? How much is being spent on these efforts? How much would it cost to go a different route? How humane are these policies?

Recognize the benefits of housing.

Homelessness is a public health crisis costing taxpayers as much as $50,000 a year for every person left chronically homeless.

Offer solutions.

Journalists can focus on what’s working without acting as advocates. “Exposing the problem isn’t always enough. People and society need ways to respond,” said Rikha Sharma Rani, a freelance writer, and a director at the Solutions Journalism Network. “The key question to ask should be, ‘Who’s doing this better? And how?’”

Oliver put it simply.

“Basically, we need to stop being [expletives] and assuming that unhoused [people] are a collection of drug addict criminals who’ve chosen this life for themselves, instead of people suffering the inevitable consequences of gutted social programs and a nationwide divestment from affordable housing.”