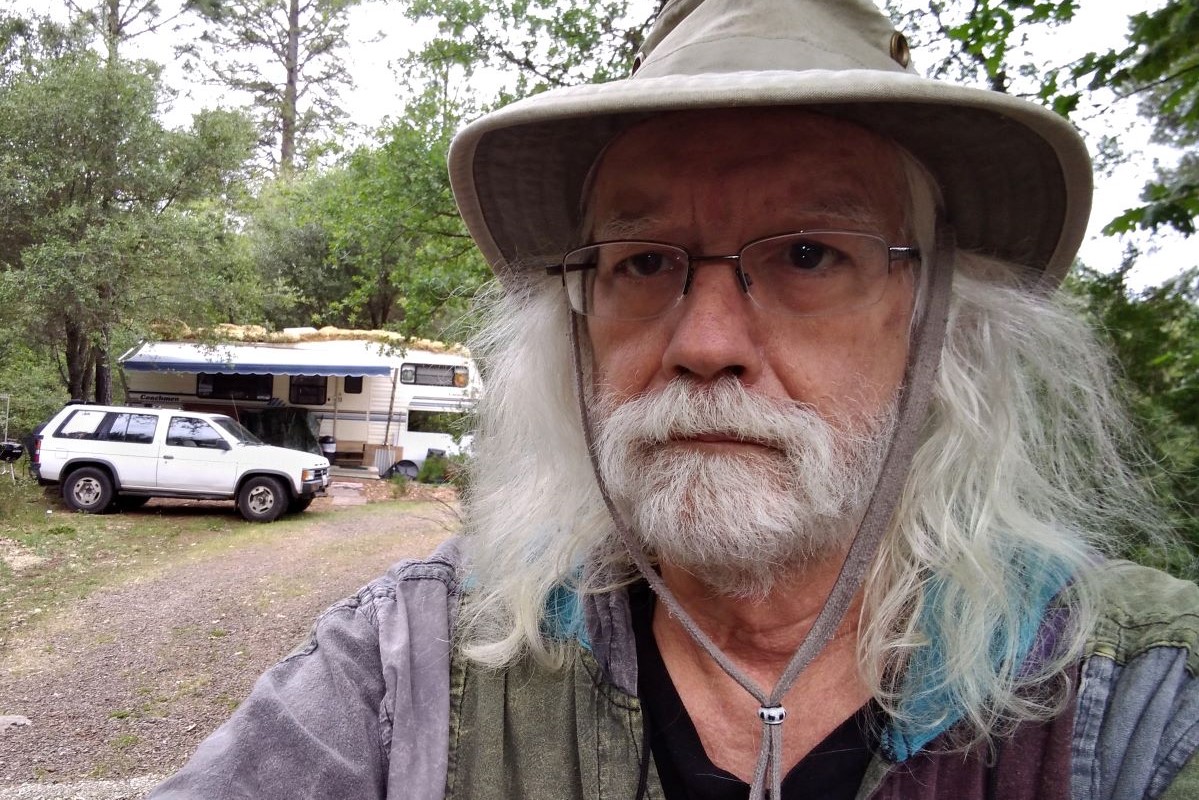

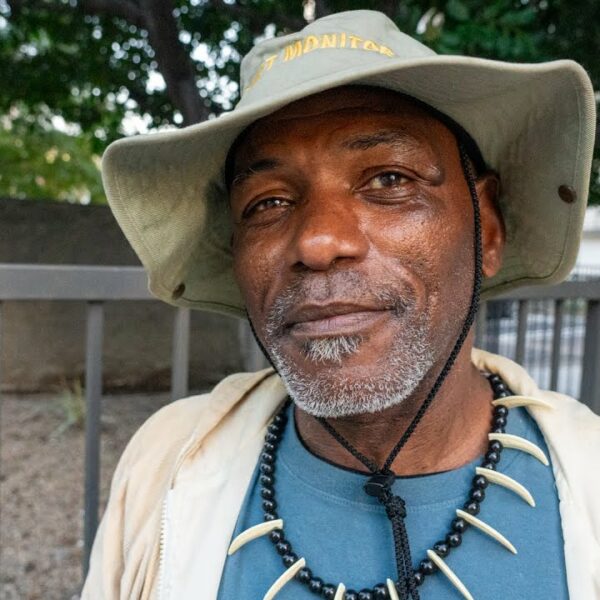

The homeless problem in America is much larger than most people realize. While the problem is obvious on the mean streets of cities and the cruel back roads of rural communities, there are legions of “working poor” people who strive daily to avoid the stigma of being branded “homeless.”

Your dental hygienist, the kid who fixes your computer, the waiter at your favorite restaurant, your child’s favorite pre-school teacher or the well-dressed woman who volunteers at the hospital could be homeless for all you know.

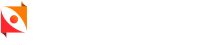

In between high-level successes, I’ve been episodically homeless on and off since 1979. Except for a small circle of friends and a few law enforcement and mental health professionals, most people never knew I often led a secret life of quiet desperation in the Sierra Nevada Foothills of Northern California. In this three-part recollection from 2008, I was living in my luxury Jeep Grand Cherokee SUV, a vestige of better times when I owned a five-acre ranch and was a highly paid technical editor …

Wake-up Call

A blinding light woke me from a dead sleep. For a panicked moment, I didn’t know where I was.

Then I saw the clock on my dashboard – 02:08 a.m. I felt my cramped muscles flooding with adrenaline as I struggled to sit up in the driver’s seat. There was a deputy sheriff tapping at my window.

From my experience as a news reporter, I figured he’d already run my plates for wants and warrants before approaching my vehicle. I knew I was not a wanted man, but my brain was consumed with free-floating guilt anyway.

The red and blue flashing lights from his patrol car added to my fear that this could be a bad night.

I really had to pee.

I lowered my electric window. “Good evening, deputy.”

“Good evening, sir. May I see some identification?”

Moving slowly, keeping my hands in sight, I pulled my heavy Mexican blanket away. I told him I was going to get my wallet out of the front pocket of my jeans and open my glove compartment. Shivering in the cold night air from the open window, I handed him my license, registration and proof of insurance.

He studied the documents. After confirming I was street legal and local, he handed me my identity back.

I reflexively mumbled, “Thanks” – and wondered what the hell I was thanking him for.

While I put my “papieren” away, I kept my mouth shut. I’d read somewhere a public defender always advised her clients to “Shut the fuck up.”

Usually, when I talked to cops as a reporter, they were afraid of me. (“You’re not going to quote me, are you?”) Not the case here. Yes-sir-no-sir seemed my best line of defense.

I was praying he wouldn’t make me get out of the car. All my blood was in my feet and my blood pressure was low.

I knew I would fall if I stood up without bracing myself on the car for a moment. I tend to faint after sitting for a long time. It’s called syncope [sing-ko-PEE! – and oh God, I had to pee.]

With spinal stenosis and other back problems, I couldn’t pass a field sobriety test stone cold sober.

The deputy leaned in close to my window. I guessed he wanted to smell my breath.

I wasn’t drunk or high. Well, not much. My little ice chest of beer and a small stash box were carefully stowed out of sight. I congratulated myself on having brushed my teeth before bedding down for the night with my Mexican blanket for warmth.

He shined his light around the inside of my car. It was chock full of stuff I thought I needed to keep with me.

The only place to sleep was to scrunch down in the driver’s seat, where I was presently cowering.

“It looks like you’ve fallen on hard times,” he said with something resembling sympathy.

Mumbling in the affirmative, I didn’t elaborate. I must have looked pathetic – I felt pathetic. I needed to piss so bad, but I was pretty sure I wouldn’t be able to in front of a cop. As I squirmed in my seat, he asked: “You need to take a leak?” He gestured toward a bush. “Go ahead.”

“No, sir.”

I looked him in the eye, then looked down. They get suspicious if you don’t look at them, but get hostile if you look at them too much.

This wasn’t the time or place to stand up for my rights. At this point, I didn’t know if I had any rights. The good news was the deputy wasn’t reading me my rights.

“You’re not safe here,” he told me.

“Yes, sir.”

“Here” was a clearing in some bushes off Idaho-Maryland Road near the California Gold Rush town of Grass Valley. No moon. No streetlights. Dark. Rural. I thought I was well hidden.

Apparently, not.

“I want you to drive back into town and park under the lights in the Safeway parking lot. You’ll be safer there, and I can keep an eye on you,” the deputy said.

“Yes sir.”

He said it in a friendly way, but I was pretty sure it was an order.

He walked back to his unit, got in, reversed the car out onto the road and parked, waiting for me, enforcement lights still flashing.

I started my car up and began backing out slowly and carefully. My neck was painfully stiff from too many nights of sleeping crooked. I had to turn my shoulders to turn my head just to see my side view mirrors. My guitar case blocked my rear view.

The deputy’s glaring lights at least gave me a target, but I think I killed a bush as I nervously maneuvered back onto the asphalt.

I slowly accelerated toward town.

I thought he was going to escort me, lights and all. Instead, he killed his light array, flashed his headlights and flipped a U to head on up the road.

I drove about a half mile down the deserted country road until I saw a wide spot on the shoulder. Pulling over, I leaped out of my car, frantically unbuttoning my Levi’s. I got halfway round the front of my car when the syncope hit. I bounced off the car and landed on my back.

Staring at the stars for a while, I thought, was I hurt? No, just stupid – and upset that I’d been woken up by a cop in the middle of the night and was now lying in the dirt. I had failed at being invisible.

Finally, I struggled back to my feet, leaned against the car and took care of business. As I watered the vegetation, I pondered what had just happened.

Was I pissed off that I been rousted by The Man – or relieved I’d been protected and served by a professional peace officer?

Let’s just say from then on, I’ve always tried to park in some brightly lit– but different – place every night.

To be continued. This is part one in a three-part series; click here for part two and part three.