There was nothing we could do.

My father had been sick since I was eight or nine, with an illness which was not well understood in the eighties, and which he would spend the next decade or two suffering both from the symptoms and from side effects of the various medications his doctors prescribed. I didn’t understand this back then; all I knew was that we were off on another adventure, moving to a place called Maine—much farther north than I had ever lived before. I did know that I preferred it to the alternative, which was for daddy to be sent to fight in this new war the people on the news were talking about.

While I don’t particularly remember missing my friends in Maryland, I will never forget the tiny forest we had behind the townhouse, with its poplar trees and the fireflies in the summer, but I didn’t miss it for long. After a brief stay with my father’s foster sister and her family, we moved into an unfinished three-story house on two and a half acres of wintergreen, blueberries, and pine trees. If I walked far enough back, I could find ferns, endangered red or yellow lady’s slipper flowers, and eventually more backyards with new friends to play with.

Daddy didn’t work anymore—not for the Air Force or even the Boy Scouts. This time mommy was the breadwinner, using her accounting degree as a teller at a bank in town. I could walk from the elementary school if I didn’t feel like taking the bus and playing with blocks in a little corner room until she got off work.

The other tellers were always nice to me. If they were annoyed at having a grade-schooler running around while mom finished her shift, it didn’t show. There was nothing about them that hinted that one of them was about to destroy my life.

The insidious thing about “white-collar crime” is that it’s so, so easy to convince yourself that it doesn’t harm anyone. A few cents here, a dollar there, taken in such tiny amounts that no one ever notices. It doesn’t add up to much, really. A few hundred dollars a month, maybe a thousand—enough to take your family on a nice vacation or renovate your rustic New England-style home into something more fashionable. It’s not like you’re getting rich.

And if someone does notice? Well, you thought things through from the beginning. You chose your mark—an unsuspecting new employee with an out-of-town accent—and made sure you only took money out of transactions she’s responsible for. You pat one of her way-too-many kids on the head and give them a lollipop from the jar on the counter, and maybe you take one for yourself too because who’s watching anyway? Never once do you think about what will happen to that kid when somebody notices the trap you’ve set for them.

Time passed. Some guy named George Bush held a rally in town, which nine-year-old me thought was pretty neat. My dad put in floors on the upper level of the house so we could have proper bedrooms, then started building a fancy dollhouse using the tools he’d bought and the wood scraps he had leftover. My mom tried gardening and composting (and failed spectacularly). I practiced roller-skating in the basement while we waited for the city to pave the street leading to our house. We even gained a foster brother. He was older than me but not as wise, constantly breaking the rules and getting himself in trouble.

One day, the bill came due.

Too many people complained about those dollars and cents missing from their accounts at the end of the month, and my mother took the fall. (Many months later, a new victim working at the bank would fall prey to an identical scheme; I don’t know whether they found the culprit.) Our only source of income was gone. Even if there had been another bank in town, they wouldn’t have hired my mother.

The dollhouse my dad spent so much time working on disappeared. So did most of our toys, and the tools, and the bunk beds. I learned what the word “bankruptcy” meant. A few things, like my hard-earned collection of Black Stallion books, could go with us; the rest had to be sold to whoever would buy it.

There was nothing we could do—no way to keep the house, no way to stay in our school district. Our “cousins” in town didn’t have space for our growing family, especially now that it included a troubled teenager. Dad still couldn’t work, and through the pitfalls of modern medicine would get worse long before he got better. I can only imagine what went through my parents’ minds when they realized they were about to be homeless with five children in the winter.

My last memory of that house is my mother telling me she was worried about the cat because she’d spotted a fox. I remember being jealous because I’d never seen a fox in the yard before, and now I never would.

We drove south toward warmer places in two cars that towed everything we still owned behind them. We communicated with CB radios because cell phones were little more than science fiction then. It was easy to get separated on busy east coast roadways. Sometimes we would lose contact, which was a little scary. I’m sure my parents must have planned where we would stop each night. Eventually, we always found each other again.

One thing I realize when I think about that month is that it could have been so much worse. We had our cars, a little money for gas and hotels on the drive down, and enough tents for everyone to sleep in. We ended up in an RV park on a U.S. Air Force base a hundred yards from the marina, which was nice. We didn’t have any torrential rains that would flood our tents and force us to huddle in the van the next time my father’s illness and a poor job market left us homeless. Unlike my disabled sister would decades later, we never had to sleep in a car in weather that was below freezing and hope it had enough gas to keep the engine running until morning.

Sometimes your best isn’t good enough. Or people take advantage of you. Or disaster strikes, and there’s no way to recover.

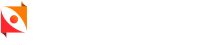

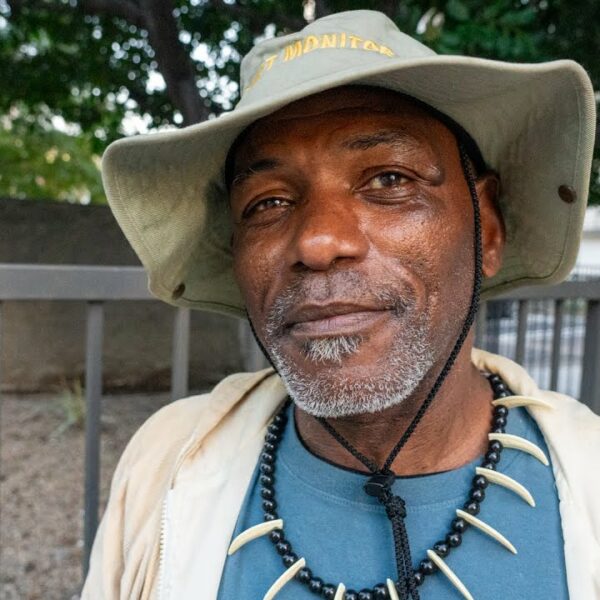

I think of all the people struggling right now. They had no more options when the world pulled the rug out from under them. Will the world judge them and decide they must have brought this on themselves? Or will people stop listing every reason they shouldn’t help and realize that homelessness can happen to anyone, even those trying their hardest?