|

7119 W. Sunset Blvd., #618, Los Angeles, CA 90046

|

|

As the visibility of homelessness grew during the pandemic, officials in communities across the country faced increasingly loud calls to do something. From individual residents frustrated by encampments in their area, to organized business and homeowner groups with a desire to “clean up the city” more broadly. In some cases, this led to positive developments, such as programs in multiple states that leased or purchased unused hotel space and repurposed it as temporary or permanent housing for homeless people. While scaling up these programs created challenges, thousands who had previously lived on the street were housed in private rooms, providing both a place to stay and comparative safety from exposure to COVID-19.

As the visibility of homelessness grew during the pandemic, officials in communities across the country faced increasingly loud calls to do something. From individual residents frustrated by encampments in their area, to organized business and homeowner groups with a desire to “clean up the city” more broadly. In some cases, this led to positive developments, such as programs in multiple states that leased or purchased unused hotel space and repurposed it as temporary or permanent housing for homeless people. While scaling up these programs created challenges, thousands who had previously lived on the street were housed in private rooms, providing both a place to stay and comparative safety from exposure to COVID-19.

While these programs made some difference, the increased visibility of homelessness on the streets has left politicians fielding complaints from frustrated constituents. Under that pressure, many cities have turned to measures that seek to criminalize and banish unhoused people. As the ACLU of Southern California noted in a 2021 report:

“Instead of meeting the affordable housing and basic survival needs of its entire unhoused population, local and state governments are responding to the increased visibility of houselessness with misguided and discriminatory strategies. Many of these tactics are designed to rid the community of the visible presence of unhoused people.”

These efforts have not only resulted in harmful policies. Along the way, leaders justified these policies with rhetoric demonizing homeless people. The report continues:

“The rhetoric that public officials use to justify these policies and practices is often dangerously dehumanizing. Without evidence, officials frame unhoused people as dangerous to housed people, particularly their children. They are condemned as a threat to public safety, and a form of blight that needs to be swept up, disappeared, and excluded from places housed people gather.”

While advocates and service providers would prefer to focus on discussions of housing policy and helpful projects, increasingly loud calls for police action are causing real harm. They are damaging the lives and prospects of homeless people, redirecting funding from serious solutions to enforcement, and contributing to an environment of dehumanization and discrimination.

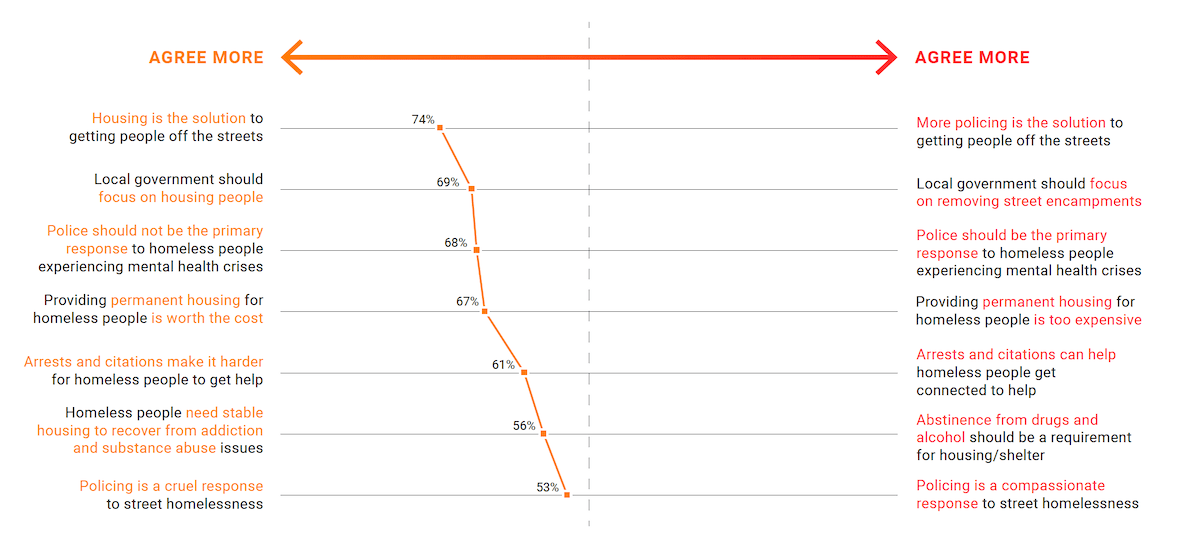

In the wake of mass protests in 2020, opinions about policing and crime feel as divided as they’ve ever been. However, there is a fair amount of agreement that the solution to homelessness lies in more housing, not more policing, and that housing should be the focus of local governments on homelessness. The public also agrees that providing permanent housing is worth the cost. Where there is more division is on individual police interactions – the public is split on the question of whether such interactions help or hurt homeless people. The public is evenly split on whether policing is a cruel or compassionate response to homelessness in general.

qC2: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your attitudes toward policing.

Public support for enforcement measures varies significantly depending on the specific policy offered. The public is sensitive to concerns about useable sidewalks and encampments near schools, with a slight majority supporting more enforcement on these specific questions. These messages are commonly used to justify enforcement policies. Finding ways to address these concerns is a crucial task for advocates.

In contrast, the public is against policies that confiscate tents or property from homeless people, and a plurality oppose removing or arresting people who decline shelter. For advocates, this offers a messaging lesson to reframe discussions of police response around the harm done to homeless people by enforcement.

qC3: Below are a few ways that law enforcement could respond to homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

How can advocates counter narratives that focus on crime and danger? One potential route is to focus on the need for basic services like trash pickup and restroom access. These services can help to address public concerns about health and sanitation and provide practical benefits to unsheltered people. Focusing on homeless people as likely victims of crime can also provide a strong counter-narrative to common tropes about homeless people committing crimes.

The majority of the public also believe that people released from prison deserve help securing housing, a finding that highlights the public’s sympathy even for those who are convicted criminals. While the public is concerned about crime, that concern doesn’t diminish the desire to see people housed.

There are also concerns about the financial side of enforcement. The majority believe that investing more in housing and services is important, even at the expense of budgets for enforcement. As cities across the country have seen sizeable movements aimed at reallocating police funding and reimagining public safety, this creates an opportunity for homelessness advocates to work in coalition across issue lines with organizations focused on policing issues.

Agree/Somewhat Agree

qC4: How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

Because criminalization and enforcement have become an outsized part of public debates about homelessness, pre-existing attitudes about crime and policing are an important part of the views people bring to discussions on homelessness. In general, trust for law enforcement remains high, and policing is seen as important to public safety. However, the public is more critical of law enforcement on questions about police funding and police bias, with a plurality believing that government should spend more on social services and that police are biased against racial minorities. As we will see, the question of police bias has a major influence on opinions around homelessness.

Because criminalization and enforcement have become an outsized part of public debates about homelessness, pre-existing attitudes about crime and policing are an important part of the views people bring to discussions on homelessness. In general, trust for law enforcement remains high, and policing is seen as important to public safety. However, the public is more critical of law enforcement on questions about police funding and police bias, with a plurality believing that government should spend more on social services and that police are biased against racial minorities. As we will see, the question of police bias has a major influence on opinions around homelessness.

qC3: Below are a few ways that law enforcement could respond to homelessness. For each policy below, please indicate how much you support that policy.

Those who believe that police are unbiased are much more likely to support police-led responses to homelessness. Compared to those who believe police are racially biased, they are nearly twice as likely to view policing as a compassionate response to homelessness, and much more likely to believe that arrests and citations are a way to get homeless people connected to services.

This is an important point for advocates to emphasize: Police interactions make getting housed harder.

While they are more likely to view police as a positive response, those who see the police as unbiased still favor housing as a solution to homelessness, with less than a third believing that policing is more important than housing.

By perceptions of police racial bias

qC2: For each pair of statements below, please select which one better describes your attitudes toward policing.

Views on police bias inform more than just people’s opinions on enforcement; they also correlate strongly with acceptance of shelter or housing in one’s own neighborhood. Among those who believe police are biased, there is overwhelming support for building shelter and housing. Those who believe police are unbiased are much less supportive, with fewer than half supporting such projects.

Views on police bias inform more than just people’s opinions on enforcement; they also correlate strongly with acceptance of shelter or housing in one’s own neighborhood. Among those who believe police are biased, there is overwhelming support for building shelter and housing. Those who believe police are unbiased are much less supportive, with fewer than half supporting such projects.

It’s tempting to view issues of race and policing as wholly separate from discussions of housing, even as discussions of these issues often overlap at the level of municipal government. But people’s opinions on housing, policing, and countless other issues don’t form in isolation. They’re part of a larger worldview that people bring to every political conversation.

For providers, advocates, and funders in the homelessness space, it’s important to be attentive to the way these issues overlap in order to be effective messengers across diverse audiences. It’s also crucial to select those audiences; these findings suggest efforts to build support for housing solutions can find organic allies in other movements and organizations fighting for justice.

By perceptions of police racial bias

By perceptions of police racial bias

QA17: If there was a plan to build a homeless housing project with on-site services in your neighborhood, would you support or oppose that plan?

QA18: If there was a plan to build a homeless shelter in your neighborhood, would you support or oppose that plan?

On May 1, 2021, voters in Austin went to the polls to vote on Proposition B, a measure “making it a criminal offense…for anyone to sit, lie down, or camp in public areas and prohibiting solicitation of money or other things of value at specific hours and locations.” This measure includes two common types of homeless criminalization laws: sit-sleep-lie bans, which ban those activities in public places, and anti-panhandling ordinances, which punish soliciting money or other items from passersby.

Proposition B was a reaction to a 2019 change that loosened Austin’s restrictions on panhandling and camping. Proponents of this last measure included the local Republican party, the Chamber of Commerce, and the union representing Austin’s police officers. While a small group of faith leaders, politicians, and other advocates fought the measure, supporters of the measure spent nearly $2 million on the campaign, outspending their opponents by a factor of roughly 10-to-1. This money was used to hammer home messages describing “chaos on the streets,” and portraying homelessness as a threat to businesses, tourism, and children.

Proposition B passed with 57.7% of the vote, thus reinstating Austin’s anti-camping laws. Others are now seeking to emulate Austin’s model. In Los Angeles, a City Councilman introduced a similar ballot measure as part of his ongoing campaign for Mayor. At the time of this writing, ballots are being cast on a Denver measure allowing residents to sue the city for removing encampments too slowly. Beyond these high profile initiatives, a 2021 ACLU report found that cities across southern California were using enforcement to push homeless people into remote areas, selectively applying laws to homeless people, and even targeting groups providing aid and assistance to their homeless neighbors.

As advocates, we’re facing an uphill battle. Enforcement strategies can be effective in reducing visible homelessness by pushing people out of sight, satisfying some voters’ desire to see people moved somewhere else. Messages should focus on more than just housing; advocates need to provide alternatives that speak to the needs of homeless residents and to visible problems. Expanding the availability of public restrooms and water fountains and providing additional trash receptacles provide realistic alternatives to aggressive enforcement that still speak to both the frustrations and the real public health issues created by human waste and the accumulation of refuse.