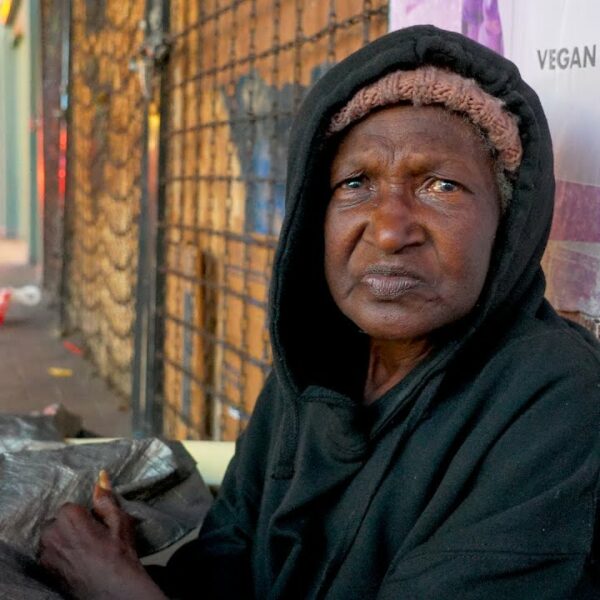

This three-part story series from 1987 is still relevant today. Employers and insurance companies still fight psychiatric work injuries with a vicious vengeance. Genuinely injured workers are treated as if they’re fraudulent criminals. Their claims are routinely denied for 90 days. Plenty of time to fall into despair, debt, depression and homelessness. Laws and litigation are designed to delay and deny legitimate psych claims.

Fortunately, I had a good case and a good lawyer. It was pure hell at the time, but just like the screenplays I was trained to write, ultimately the worst thing that happened to me turned out to be the best thing.

Lost and Found in the Ozone

I wonder if you get extra points for hitting the water? The American River was just a thin ribbon of water at the bottom of the canyon, 730 feet below.

That’s a long time to think about it on the way down …

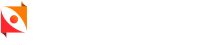

It was dawn, sometime in April 1988. I was admiring the view from the Foresthill Bridge near Auburn, California. At the time, that rural bridge was the second-most popular jumping-off spot in the state, right behind the Golden Gate.

I don’t think the Prozac is working, I decided and walked back to my car. I drove back to Marty’s house in Sacramento.

The previous August my doctor had benched me as psychiatrically disabled. I’d lost 30 pounds and was mindlessly running red lights. I’d just turned 40 and was facing the cold, hard reality that my son was better off with his mom.

For most guys, a mid-life crisis involves a woman or a sports car. Me, I got a nervous breakdown.

My doctor told me to go home and definitely not go back to work. I didn’t know what it meant at the time, but she filed a psychiatric workers’ compensation insurance claim on my behalf.

Turns out, what it meant was that I was fucked up. I wasn’t eligible for unemployment, was a danger to myself and others, and the insurance company wasn’t going to even deal with the claim for 90 days.

For the last four months, I’d been working 80+ hours a week as editor of the Colfax Record, a small-town weekly newspaper in Northern California.

I had been blackmailed into the job. I’d been working as a part-time reporter for the Auburn Journal, a daily paper that had just bought the Record. Since I had previous experience working the Colfax beat, I was told to either take the job or get fired.

Having previous experience working the Colfax beat, I did not want the job.

Colfax is popularly known as “a small drinking town with a railroad problem.” Dirty politics is the town sport. The whole place was something out of a Sinclair Lewis novel.

In a city (Colfax was technically a city) of fewer than 5,000, the newspaper editor ranks with the mayor, police chief, fire chief, undertaker, and president of the chamber of commerce. There is no way not to be involved in community affairs.

Even though I didn’t want the highly stressful job, it’s my nature to do whatever I do to the best of my ability. Promised a half-time reporter who never materialized, I proceeded to work eight days a week.

Every week, I’d spend up to 40 hours straight putting the weekly to bed. Except for a botched three-color separation for the July 4th edition and being suckered big time on a front-page, feel-good story, people told me I was doing a good job.

Crazy people know they’re crazy. Insane people don’t. I was insane.

I had a second story apartment in an old, converted house. Perched on a cliff, it overlooked the Colfax railroad station. I was eye level with a microwave tower. The toilet leaked.

I had a pile of bills and a screw-you letter from the insurance company. I was unemployed and with a pending workers’ comp claim, unemployable both legally and psychologically.

A dear Jewish friend brought me some chicken soup. A colleague from the Auburn Journal came by to express his condolences. A local minister called me up and prayed over me. I think it made him feel better.

“You look like you were flushed down the toilet and pulled back out,” a neighbor observed.

I was getting a lot of sympathy but not much in the way of help. I wasn’t exactly estranged from my family, but we weren’t close either emotionally or geographically.

The only person who cared enough, and who was in a position to help me, was my friend Marty (not his real name).

Marty can sometimes be a pain in the ass, but you can have no better friend. I was in desperate need, and Marty saved my ass.

He kept insisting I come down from the foothills to Sacramento and live with him and his two young children, Maria, 11, and Stephan, 7 (not their real names either). He had a big house and a bigger heart.

Although he claims we co-founded it, Marty started the Sacramento Single Fathers Support Group. I joined the group because I needed support and knew how to write press releases. We had monthly meetings teaching single fathers everything from children’s nutrition to custody rights.

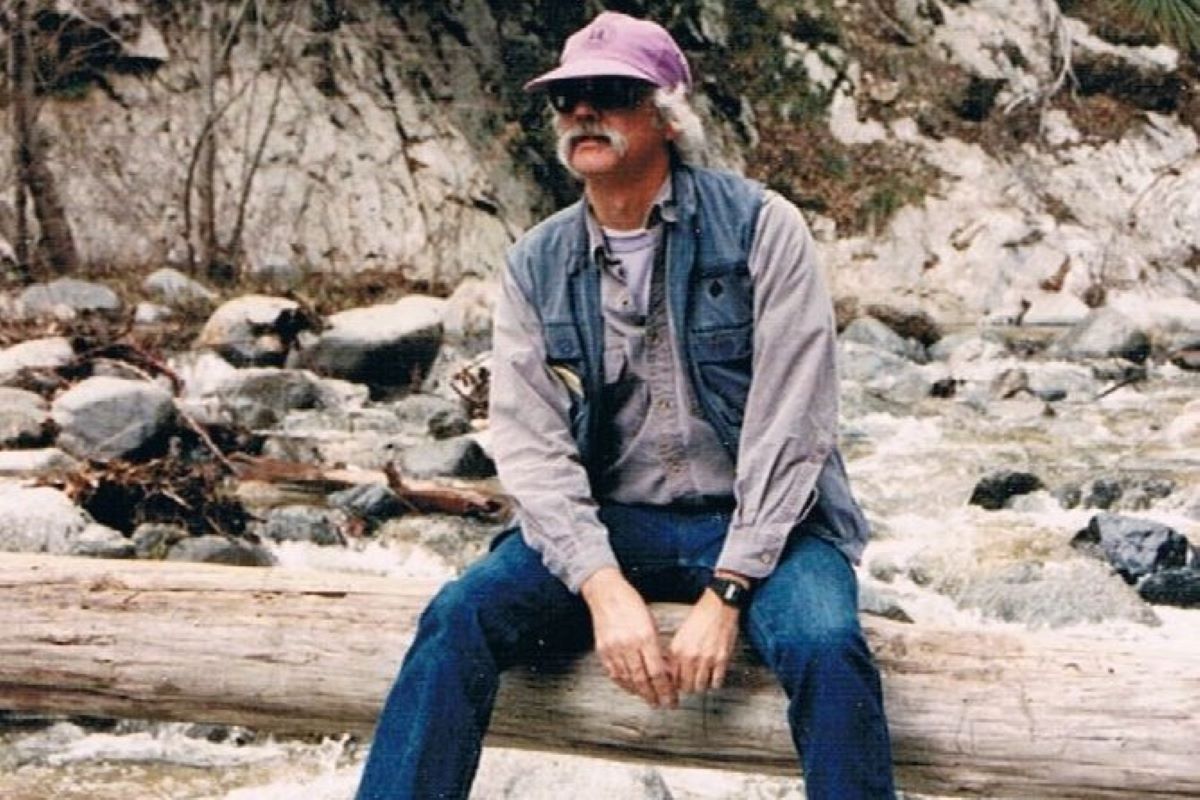

Marty was a fierce social activist, a registered Communist and former Catholic oblate with a history of boxing and street fighting. Married twice, to the same woman, Marty had sole custody of his kids.

My kid lived with his mom (a wonderful woman) in Los Angeles.

Despite his refusal to sign a loyalty oath, Marty had won a lawsuit against the California Department of Education allowing him to keep his job. The state retaliated by assigning him to migrant education.

Ironically, Marty was uniquely qualified for the job, but it did put him on the road a lot.

I did not want to go back to a real city, but he was making me an offer I couldn’t refuse. I needed someplace to go, and if I couldn’t take care of my son, I could at least stand in loco parentis for Maria and Stephan.

In part two, Marty gives me shelter from the crazy storm in my head as I begin to put my life back together. Still “technically homeless,” I go to workers’ compensation court and back to college.