Psychologically, physically and socially, I’m a failure of both nature and nurture. Genetically predisposed to psycho-affective disorders and spinal defects, I grew up in an emotionally violent home.

Despite a world-class education and a passing fair talent as a multi-genre writer/photographer, my life has been a bipolar series of high-powered career successes and episodes of dysfunctional homelessness.

In 1987, the physical and emotional stress of my job triggered everything that was wrong with me. I was plunged into a helpless fugue state with suicidal depression. If it weren’t for a true friend, a good lawyer and a great voc-rehab counselor, I’d probably be dead.

Part one chronicled the crash-and-burn – and rescue from total homelessness. Part two showed how “technically homeless” can be a good thing. Part three is all about karma.

If my friend Marty hadn’t taken me in, I would have ended up on the streets in a mental hell.

Instead, I took my mental hell and went to live with Marty and his kids Maria, 11, and Stephan, 7. Marty’s a hard-charging kind of guy, and he’s always expected a lot of me, which is good. But he quickly learned telling me to “Snap out of it,” just annoyed the hell out of me.

“It’s hard to fight an enemy who has outposts in your head.”

~Sally Kempton

Living with Marty and his kids made me “technically homeless,” according to a 1988 NBC news special. Aka the “hidden homeless,” we are people who have temporary, habitable shelter, usually in the home of friends or family.

I knew I would have to leave Marty’s home sometime. But at the time, I’d just enrolled at Sonoma State University, had just begun psychiatric treatment and was enjoying life with Marty and the kids as an adopted member of their family.

I remember taking sports shots of the kids playing soccer. Stephan always had a big grin on his face when he was kicking the ball. Maria broke her arm.

Shortly before Christmas, my lawyer won my psychiatric workers’ comp claim.

The win was based on a chillingly accurate, 13-page diagnosis written by a psychologist who seemed to find me fascinating.

In not so many words, the psychologist concluded I’d always been crazy but my employer had made me go insane. His report said I was genetically bipolar with a borderline personality disorder (avoidant, passive-aggressive and schizoid) exacerbated by a traumatic childhood. He determined I was totally and temporarily disabled because of work. He recommended psychiatric treatment and vocational rehabilitation.

Getting officially diagnosed was strangely validating. It explained a whole hell of a lot about my life up to that point.

My son once asked my sister if she thought he’d inherit my problems. She just laughed and said, “Oh, hell no. We knew Tom was strange when he was 10.”

My many years of therapy, peer-training and actual experience had taught me how to cope, sort of. Most of my social skills were just learned behavior.

The prospect of a medical miracle for my disorder was encouraging.

My psychiatrist, however, was a supercilious asshole. I knew more about therapy than he did. And I damn sure knew you didn’t put a 4×6-foot photograph of one of your patients, a major football star, on your office wall.

All I got were negative side effects – trembling hands, low blood pressure, weight gain, brain fog, and suicidal tendencies.

Always before, I’d just thought about suicide. Prozac inspired me to actually explore the possibilities. As I said in part one, I considered a 730-foot high dive off the Foresthill Bridge.

Another time, I stood on the edge of a narrow two-lane highway in the dark of night. I picked out heavy trucks speeding toward me and tried to guess exactly when I could jump in front of one.

Although I was to be an experiment in better living through psychiatric chemistry for the next 20 years, the pills never did much good. Now, I just take a generic Ativan whenever I feel too scatter-brained to concentrate.

Over the next year and a half, I attended Sonoma State on my workers’ comp settlement and several scholarships.

I didn’t take the required courses to earn another master’s degree. Nevertheless, I walked away happy with a 3.7 grade point average (B’s in tennis) and invaluable knowledge about computers.

My self-important charlatan of a shrink declared me “permanent and stationary” (as opposed to total and temporary). He gave me a list of psych medicines to keep on trying. WTF?!

Turns out permanent and stationary mostly meant the insurance company wasn’t going to pay him anymore.

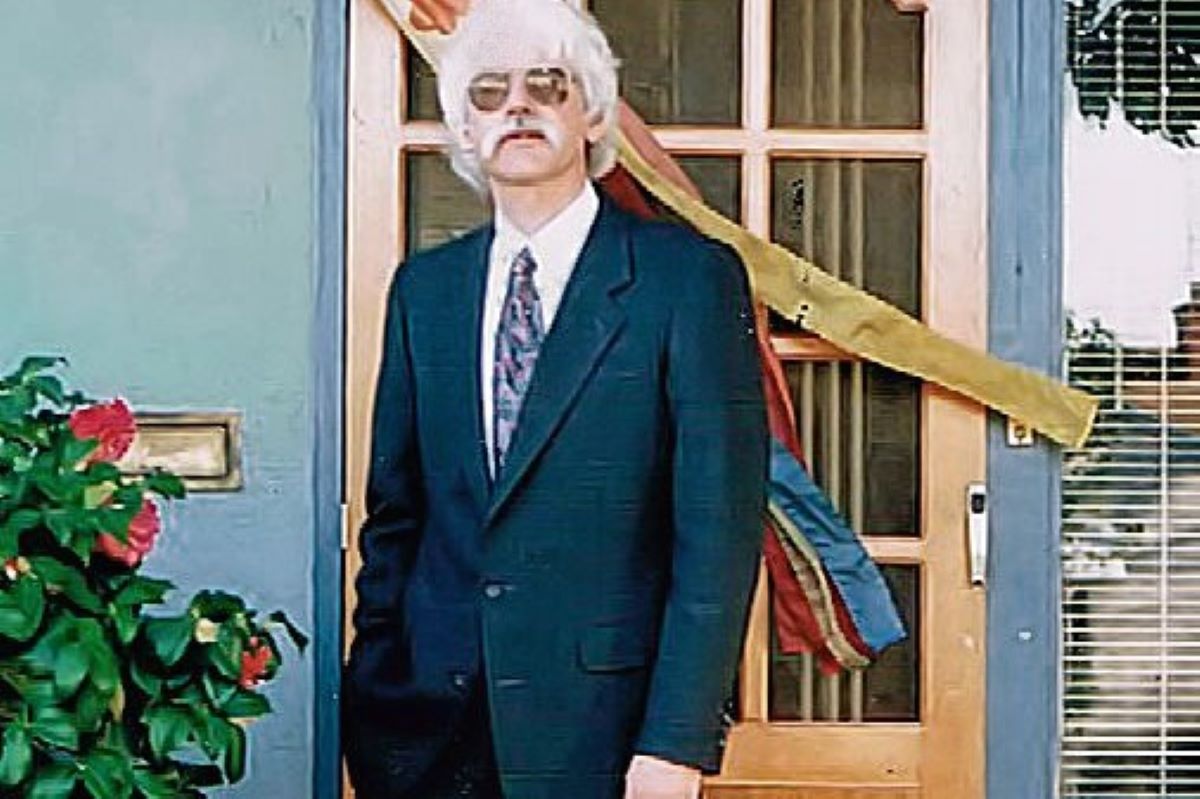

My voc-rehab counselor Mark took a personal interest in me. He told me to absolutely stay away from journalism. He bought me a “zoot suit” and sent me to the Sacramento Business Journal to pick up their annual edition of Sacramento’s top companies.

The idea was to find a cushy job doing PR or writing ad copy.

So, dressed to look like a success, I went downtown to pick up the slick publication. Out of habit, I asked the girl at the front desk if there were any job openings.

“I think they need a copy editor,” she said.

A year later, I took Mark out for a business lunch at one Sacramento’s finest restaurants on the Business Journal’s dime.

Meanwhile, none of us – Marty, Maria, Stephan nor I – remember exactly when I left their home. But I do remember how Marty tried to tell me it was time to leave.

Marty and I come from different generations and different cultures. Telling me my shoes smelled, he began leaving them outside the front door. He insisted I scrub the bathroom floor on my hands and knees. He turned down the heat to my room.

I found his behavior curious. My shoes didn’t smell and it was cold, but it was his house. If he wanted the bathroom floor scrubbed, I was happy to do it.

Finally, one day, he just opened the door to my room and said, “I need my space.”

Oh. Duh. Picking up on subtle cues was not one of my learned behaviors.

Shortly thereafter, I found a cool house with roommates back home up country in the Sierra Nevada Foothills near Auburn. I was happy to leave the city life of Sacramento (although I commuted back down every day for work or school).

To this day, Marty and I are still friends. When I wrote Marty in Oregon to fact-check my memory with his, he wrote back:

“The months with us were like yesterday. You were part of the family and we loved you. … Brings back so many good feelings.”

And I love you too, brother. I will be forever grateful to you for giving me shelter from the storm.

A Karma Coda

Coincidentally (or maybe not), in 1992 I met Mark for the last time. I was taking notes at a California Senate committee hearing on workers’ compensation reform.

One of the witnesses was testifying with quiet passion in support of injured workers:

“I’ll take a rate cut, but I won’t sit behind my desk and tell an injured worker his life is over.”

Cool quote, I thought, scribbling on my notepad. Got to get an ID on – oh wow, that’s Mark!

Laid off by the Business Journal, I had advanced to legal editor of the California Employee Relations Report, a C-level newsletter for lawyers, legislators and lobbyists. I was a card-carrying member of the California state press corps, a unit chair of Local 35 of The Newspaper Guild, and I was now an expert in what had happened to me in 1987.

After the hearing, I surprised Mark in the hallway. We were both proud of and happy to see each other.

I was still wearing his zoot suit.