2020 Study Shows Students in Unsheltered Situations Increased by 137 Percent

I spent a considerable amount of time at the kitchen table during my school years. There were other places to study in the home, but something always drew me back to the kitchen, where homework had been done for generations. The math problems and French verb conjugations that old veneered table saw…

More than two decades later, those fond memories of doing homework around the kitchen table mean more to me. Having a warm, safe place to study helped me create positive connections between home and school, a well-worn path on which grass never grew save for the summer.

The Kids Aren’t Alright

Perhaps it was reading a study released by the National Center for Homeless Education that stirred the recent flood of memories. According to the most recently collected statistics, there are approximately 1.5 million homeless children enrolled in public school districts in the US. That’s the highest figure in more than a decade. School children aged 10-11 and 16-17 are the most likely to become homeless, increasing by more than 20 percent during the study’s three-year period.

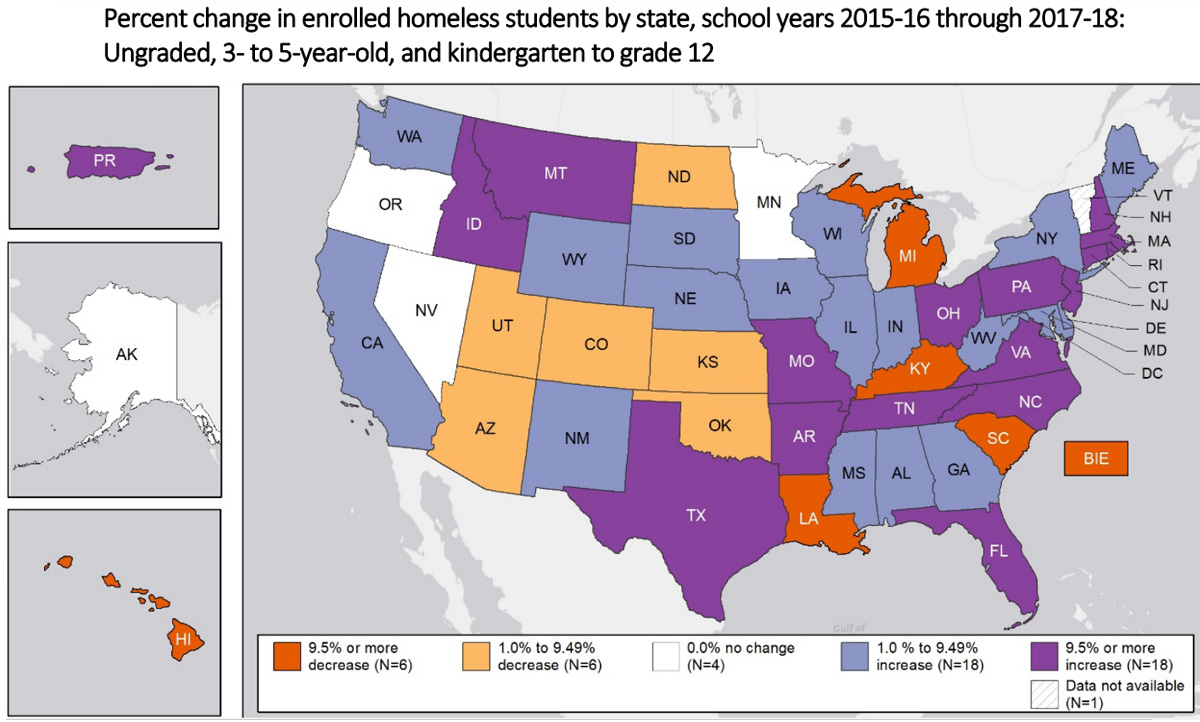

Image courtesy of EHCY Federal Data Summary SYs 2015-18

These figures mark a sharp increase in the number of homeless school children, 15 percent higher overall than the 2015-16 school year. The findings weren’t an anomaly, but rather a trend. Sixteen states reported a 10 percent or greater increase in homeless student populations. During the same period, the number of students in unsheltered situations increased by 137 percent.

It’s those unsheltered situations that are particularly concerning for homelessness advocates. The study found students living in cars, abandoned buildings, “places not meant for humans to live,” and substandard housing. A startling 7 percent of homeless school children live in these types of situations, up from 4 percent during the previous period. This marks a significant shift.

Why?

The National Center for Homeless Education reports that “historically, shifts in the type of primary nighttime residence used by students experiencing homelessness have been consistent with increases in the student population.” In other words, normally the number of homeless students changes, but the type of housing remains relatively stable.

For homeless school children, the primary residence is referred to as “doubling up” – living with other families or friends after losing their homes. This remains the case, with 74 percent of homeless school children living with other family or friends. But a greater percentage of children are living in either unsheltered situations or in hotels or motels, the latter’s usage increasing by 24 percent.

Academic Impacts

Now for the least surprising conclusion you’ll read today: Being homeless adversely affects academic performance.

Amanda Clifford of the National Youth Forum on Homelessness connects the dots:

“Homeless children are in crisis mode, and because they don’t have the luxury of focusing on school, they often fall behind.”

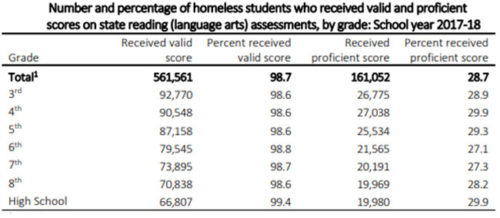

Statistics support these suspicions. Less than three in 10 homeless students achieve proficiency on state reading assessments.

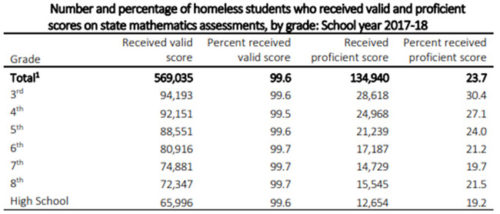

The ratio was closer to two in 10 for attaining proficiency on state mathematics assessments.

It’s not difficult to understand why homeless school children underperform academically. Many homeless youths struggle to gain continuous access to education. Interruptions to regular school attendance are an unavoidable byproduct of unstable housing.

There are also practical considerations, such as one’s living accommodations being prohibitively far away from their school or health problems due to stress. Financial needs can outweigh educational ones. The decision between preparing for the next exam and picking up a work shift becomes a no-brainer when you don’t know where your next meal is coming from.

Public schooling presents plenty of pressure all on its own. Imagine trying to successfully navigate those years while also experiencing homelessness. That’s the reality for 1.5 million youths in the US.

The Coronavirus Connection

Of course there is. Everything is just a bit worse now, isn’t it?

Unfortunately for Destiny, a 17-year-old student in Washington, her day-to-day illustrates this well. She’s technically homeless, having recently lost her primary residence. Destiny now lives with her grandmother. With so many shelters closed in her area, she’s not sure where she’ll head next if she must move again.

A quick on-set fever and strict health authority guidelines meant that Destiny was forced to quarantine with her grandmother and brother in a cramped one-bedroom apartment. Now with school closed due to coronavirus, she’s lost the one constant she’s had in her life.

“I’m on edge all day long. Everything was really good until recently. I’ll survive. It’s just actually really hard.”

Schools, community centers, libraries – places that students like Destiny usually seek out for refuge, places that might just give them a semblance of stability in a chaotic world—have shuttered their doors. No wonder Destiny is “on edge all day long”. She has no outlet, nothing to ground her. There’s nothing to diffuse the daily pressures of youth and school and growing up during a pandemic.

“I’ll survive.”

More than a million students like her will likely do the same. They’ll just have to do it without an old veneered kitchen table.