New Report from the Department of Housing and Urban Development Is a Wake-Up Call for Better Planning

During the height of the coronavirus crisis, the Centers for Disease Control called for a pause on clearing homeless encampments unless individual housing units were available for people to take shelter. Their reasons were sound. Clearing encampments leads people to disperse throughout the community, which could spread the virus. It also breaks relationships and support networks established among residents of the camps and between residents and community support services.

But another reason to avoid clearing camps has arisen. This one may make cities sit up and take notice. That’s because this time, it’s financial.

A breakthrough report on encampments and the costs associated with them has been published by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It shows that managing and sweeping away encampments comes with a hefty price tag. It’s a wake-up call for better planning.

The report, conducted by Abt Associates, conducted site research in four cities – Chicago, Houston, San Jose, and Tacoma – and reviewed procedures in five others. Overall they found a breadth of policies. However, most cities follow a plan that includes trying to connect encampment residents with social support services while conducting routine cleaning and periodic clearance of encampments.

It’s essential to understand the reasons that people seek shelter in encampments.

According to Abt’s research, a lack of affordable housing is a crucial factor. Second is the nature of the shelter system, which may come with rules or entry times that unhoused individuals can’t meet.

Some shelters are gender-specific, and clients don’t want to be separated from partners. Others don’t accept pets. In some cities, there aren’t enough shelter beds to meet the demand. Also, compared to shelters, some camp residents find more autonomy or community in an encampment. They have the ability to come and go with more privacy.

Encampments often grow up on vacant property, under highway overpasses and in parks. When they’re on public land, cities routinely clear them out in the name of sanitation. Both managing and clearing these camps gets expensive, according to Abt.

In 2019, the following cities spent millions of dollars on clearing homeless encampments:

- Chicago spent $3.5 million

- Tacoma spent $3.9 million

- Houston spent $3.3 million

- San Jose spent $8.5 million

San Jose has about six times as many homeless people as Chicago or Houston, with 7,922 unhoused people. Tacoma had the fewest unhoused individuals with 629 people.

Because these are local issues, cities cannot tap into money from HUD to help defray the costs. That leaves them footing the bill.

But it’s proven to be a slippery problem.

When authorities clear one camp, homeless residents generally just move to a new encampment rather than moving into a shelter. They’re often reluctant to leave the support network that has been established within the camp.

In Las Cruces, NM, one organization has developed an interesting solution to the problem that may help homeless people while saving municipalities money.

Nonprofit Mesilla Valley Community of Hope built a campsite named Camp Hope, which features three-sided wooded structures. Homeless people can pitch tents and sleep protected from the elements. There is also a kitchen on-site and bathrooms with running water. Residents help protect the property by engaging in round-the-clock patrols. The facility is relatively small, with a few dozen campsites. However, the total cost to run it is just $12,000 per year.

But even solutions like that are still stopgaps. The ultimate answer to encampments is affordable housing.

In March 2021, President Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act, a $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package that contained nearly $50 billion for housing and homelessness:

- $5 billion will go directly for housing vouchers, available through September 2030.

- Another $5 billion is designated for rental assistance, supportive services, developing rental housing, and permanent affordable housing.

- $100 million is designated for housing counseling through NeighborWorks America.

- At least 40% must be distributed to organizations that reach minority and low-income homeowners and people experiencing homelessness.

Biden is also focused on keeping more people from becoming homeless as a result of the COVID crisis. His plan designates an additional $100 million in rental assistance to help rural households currently in USDA-financed homes. Tenants can use the money to cover back-rent and ongoing rent needs. $750 million is also going to tribal nations and indigenous peoples.

Soon after the relief package, Biden unveiled his Infrastructure plan, which calls for $213 billion allocated toward housing, including building and refurbishing affordable housing.

The bill calls for 500,000 homes to be built or rehabbed in low-to-middle income communities and creating an additional 1 million properties. He also calls for eliminating zoning laws that have disenfranchised low-income buyers and pumped up housing costs.

Biden is pushing for expansion of the Weatherization Assistance Program to help low-and-middle-income homeowners be able to turn their homes into energy-efficient dwellings.

HUD and Abt conducted this study before the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, it acknowledges the situation is likely even worse now. Still, it ultimately concludes, the basic premise hasn’t changed:

Homelessness is “the tragic result of the country’s affordable housing crisis that stems from a combination of increasing rates of deep poverty and a lack of deeply affordable housing.”

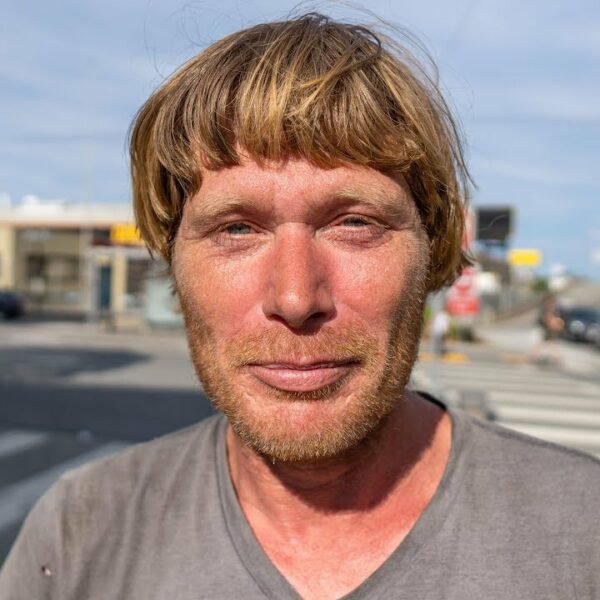

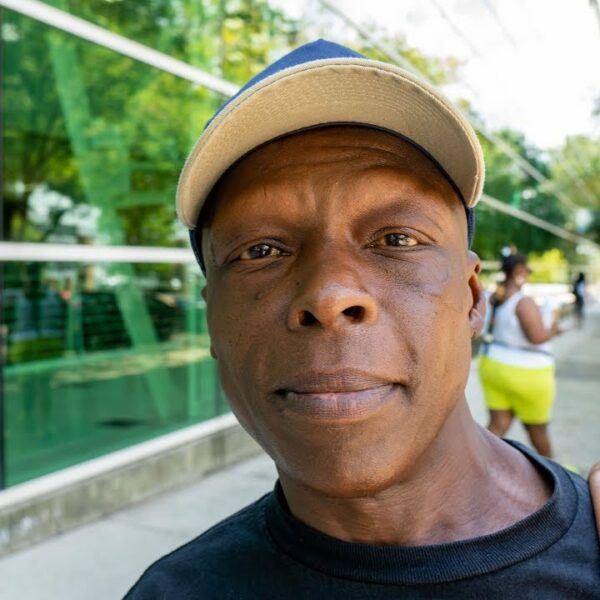

Although demographics vary by city, Blacks and Latinos are overrepresented in the homeless populations in every city studied. Some people prefer encampments over shelters for the sense of autonomy, privacy, community, and safety they feel they offer.

“Future research on the characteristics and costs of encampments should integrate the perspectives of people with lived experiences in encampments. Research should also examine the racial inequities between those who live in encampments, how encampment residents are treated under the law, and who receives supports to enter shelters or housing.

“Finally, future research should seek to incorporate a fuller accounting of the cost to cities, including additional municipal costs (for example, from police, fire, and health departments) and the costs associated with residents’ trauma when faced with clearance and closure of encampments. This fuller accounting of the costs of encampments should also be compared to the cost of employing a Housing First approach to residents of encampments,” the report concludes.