Santa Barbara, California is a town of haves and have nots. Despite its reputation for being an exclusive, beachy resort destination, homelessness and lack of affordable housing are prevalent. In order to help address the homelessness crisis, Santa Barbara recently installed 20 Pallet Shelter fiberglass homes. These look like portable tool sheds and serve to temporarily house and support a small contingent of homeless people, who were previously living in tents in a local park.

Amy King, the CEO of Pallet, said the company deliberately did not include kitchenettes or bathrooms in the design because the tiny homes are meant to be temporary. In fact, they were originally created for the purpose of assisting people after natural disasters, such as hurricanes and floods.

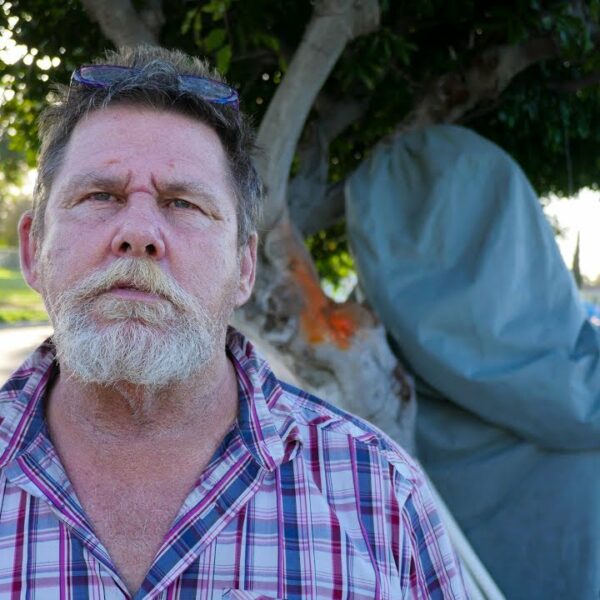

For the most part, in Santa Barbara, homeless people are purposefully ignored by residents. A Point-In-Time Count mandated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development conducted in January 2020 prior to the pandemic counted 1,897 homeless in Santa Barbara. On State Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, residents hurry past the homeless population with averted eyes to avoid seeing unpleasantness. Yet most of these people are from the community, fallen on hard times.

Priced Out of Housing

In a study conducted by the Santa Barbara Grand Jury, it is reported that 76% of the city’s homeless people were living in Santa Barbara county when they first became homeless. 40% are females and, horrifically, one in eight school-aged children in the county are homeless, one of the highest rates of child homelessness in the state.

The median home price in Santa Barbara is $1.7 million, making home ownership inaccessible to the majority of residents. Over 60% of Santa Barbara residents are renters and the county ranks third in California (out of 58) for having the highest burden to renters, in the form of high rents and vacancy shortages. There is a tension between the community’s desire for paradisaical lifestyle and the burden of how to assist homeless people.

Local ordinances against loitering have been enacted. Shouting or urinating in public have resulted in calls to law enforcement. When homeless people become too visible, the community reacts harshly, often punishing them. Recently, cities within the county have proposed ordinances against dumpster diving, leaving carts with belongings on the street, and encampment bans. None of this is designed to help homeless people but rather to persecute them for being unfortunate.

The tiny homes in Santa Barbara were initially a response to a different problem.

The homeless encampment in a park in Isla Vista, home to the University of California Santa Barbara, had overtaken the park. Local officials wanted to overhaul and improve the long-neglected park through landscape improvements and maintenance.

In order to clear out the park, the county devised a plan, funded by the Cares Act, to install 20 tiny Pallet Homes to relocate some of the park residents. The number of pallet homes was constrained by space in the new site, the parking lot of the Isla Vista Community Center.

Because of COVID, each 8×8-foot tiny home would house one person, except for couples or people who sheltered together in a tent previously. They are designed to accommodate up to 4 people in drop-down bunks. Each unit has a power outlet, an electric heater and a locked personal storage area.

The 20 units in Isla Vista house a total of 28 people. Residents were selected by social workers and people from Good Samaritan Shelter, the manager of the project. Medically fragile, elderly and women were prioritized. Even so, when the park was emptied, 20 homeless people were forced to find a new campsite due to capacity constraints and, in some cases, unwillingness to participate.

In six months, the shelters will be moved to another county.

Director of Good Samaritan Shelter Kirsten Cahoon said, “Our plan is to get everyone housed by June.”

In order to achieve this goal, care providers from Doctors without Walls, Behavioral Health, Public Defenders and Social Services visit the site regularly to offer assistance.

Adam Scofield, a resident who has been homeless on and off for most of his life, is currently sharing a unit with his brother. Being in the shelter has enabled his brother to finally have surgery to fix his detached retina.

In most cases, homeless people are unable to get much needed surgery because they lack a safe discharge plan. Cahoon added that Scofield’s brother is not the only one in the project to finally qualify for a necessary surgery.

Another resident of the tiny home community Stevo Laakso said he was “very happy” there. In addition to much needed social services, he was very pleased with the clothing and shoes provided and bathrooms with showers with towel service.

Laakso said he spent over three years living in “Slab City”, an off-the-grid squatter community in Imperial County. He described living there as “lawless insanity”, where crimes were perpetrated against neighbors regularly. Laakso said he was very satisfied with his unit, appreciated the heater and the power outlet and the ability to lock the door and sleep peacefully.

Laakso was born on an Army base in Germany. After September 11th, his identification became obsolete. However, because he lost touch with his family and had spent much of his life drifting, he had no way of obtaining new documentation. As a result, he failed to qualify for many social programs including Section 8 vouchers and other services. Good Samaritan is currently helping him obtain documentation.

Cahoon said lack of proper documentation is a common problem among homeless people, who frequently lack the tools and agency to solve such problems on their own.

Cahoon said the community in Isla Vista has been mainly supportive of their efforts. Business owners asked a lot of questions in the beginning. But since these homeless people were already in their neighborhood, in tents in the park, most agreed that it was a better solution for both the people living in tents and the surrounding community.

IV Bagel Café, located across the street, sends over their day-old bagels and pastries. Friendly college students drop by with leftovers and smiles. The shelter recently received a donation of an outdoor movie screen and projector. Officials have been showing movies to the residents in the evenings.

In order to qualify, each resident has to agree to abide by the rules, which are aimed at reducing harm. These include:

- No drugs or alcohol on the premises

- No food in the pods (pests)

- Adhere to a curfew

- No covering the windows

- No clutter outside the units for fire safety

- Each person must participate in case management

While rare, Cahoon reported that disciplinary action has been required; one person was ejected for failure to comply.

“It has to be a safe space for everyone,” she explained, “We have a zero-tolerance policy for violence.”

Hopefully, Cahoon meets her goal of getting each of her residents permanently housed by June.

At $45,000 all-in per unit ($4,900 for the Pallet shelter), it seems like a good value proposition compared to the 8 x 8-foot aluminum sheds being used in LA to house homeless people at $130,000 per unit. There, a 50-unit tiny town cost $5.2 million. At $8,600 for each prefab unit, the bulk of the cost in LA went to preparing the site, including:

- $122,000 for underground utilities

- $253,000 for concrete pads (one for each shelter)

- $312,000 for an administrative office and staff restroom

- $1.1 million for mechanical, electrical and fire alarms

- $280,000 for permits and fees

Additionally, LA budgeted $651,000 to connect to the street sewer line and $546,000 in design, project management and inspection costs. Tiny home communities are being used in Seattle, Riverside and Sacramento as well.

Time will tell whether these tiny home projects are a success.

Good Samaritan points out that just being able to lock the door at night and lock up one’s belongings affords people a sense of security and improved mental health. In addition, everyone is required to participate in case management, and security is onsite to protect the well-being of residents.

The real measure of success will be placing these individuals in jobs and permanent homes. One resident in the Isla Vista project recently got a job at a pizza parlor.

Let’s hope these shelters provide more than temporary respite from street life and equip residents with the tools necessary for self-reliance. When asked if there as anything she needed that she didn’t have, Cahoon responded, “Give these people a chance. Give them jobs.”

In doing so, you can save a life.