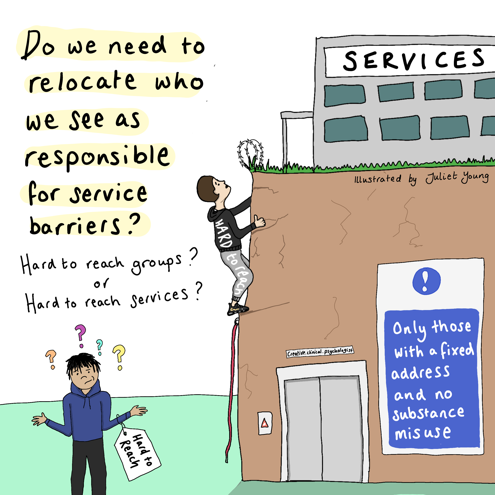

Anyone with experience working in outreach or crisis services may be familiar with the description of hard to reach, a catch-all label often used to describe people who need support but, for one reason or another, aren’t getting the help they need. What if we flipped that and asked:

“What makes these services hard to reach for the people that need them?”

That question formed the basis of research I started in 2019 through the University of Liverpool in the UK. It aimed to put the voices of homeless people at the forefront of real-world conversations on getting access to support, particularly around accommodation and addiction. It also examined barriers that can often be put up by the very organisations designed to help.

Graphic courtesy of Juliet Young

Nowhere was it more vital to highlight current issues and opportunities in homeless care provision than in the cases of rough sleepers, those most vulnerable to physical and psychological injury as a result of their circumstances. “Good enough” care, a term coined by Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott to describe care that need not be perfect but must meet core needs of stability and safety, was the yardstick in relation to how people (both service users and providers) interacted with the structures built to offer such care. I found frustrations on both sides of the conversation.

Services might put up invisible barriers, making people jump through hoops for the help they need. Meanwhile, providers often find their hands tied by policy and administrative limitations, which might see perfectly viable support candidates turned away prematurely or worse, receiving no help at all.

The result? Those who are vulnerable and experiencing the dual difficulties of homelessness and addiction find mainstream services such as community mental health teams to be beyond their reach.

Though there were many interviews conducted with volunteers with real-world experience of such issues, chilling accounts of dehumanisation and frustration were nowhere more apparent than in the story of Kate.

She told me about repeated assaults and abuse from the public and the police. When she did get support from statutory services, she was sectioned and driven far away from home only to be discharged back to the streets again with no support network or safety net.

“They sectioned me… [put me] in a hospital transport with blacked-out windows… they took me there, and I didn’t know where I was. My mind wasn’t functioning. Didn’t have any form of contact with anyone, didn’t know where I was. I was on my own. They wouldn’t tell me where I was. They wouldn’t pull over so I could have a smoke. It was scary. It’s like being passed from pillar to post. I felt really bad. I wanted to finish my life.” – Kate

For Kate, the gaps in services seem obvious. For others, it was frustrating asking for help. Those who did were often told they didn’t meet criteria such as needing to be abstinent to access addiction services.

In the case of many hostels, rules were enforced strictly. This meant not being able to get somewhere to stay overnight because couples weren’t allowed, dogs weren’t allowed, or you needed a referral from a caseworker who didn’t have an out-of-hours point of contact.

Kelly spoke about her experiences in a particular hostel, making the distinction between somewhere that was just a “roof” and somewhere that was safe and secure:

“I don’t think [hostels] look at the vulnerabilities of the person. At [a hostel], if you’re not back by a certain time, they won’t let you back in, which is ridiculous. You’ve got lots of women prostituting themselves, escorting. There’s men there, smoking spliffs, and the staff doesn’t say anything. And I just think, what? When did this happen? it’s a roof over your head, but it’s not good for people, not for vulnerable people.” – Kelly

In contrast, if there were no rules in place, it felt unsafe; there was a risk of falling in with the “wrong crowd” or being assaulted.

Throughout people’s experiences, there were visible and invisible rules. Some felt punitive, particularly when applied without compassion or wisdom. Some helped by establishing clarity and safety.

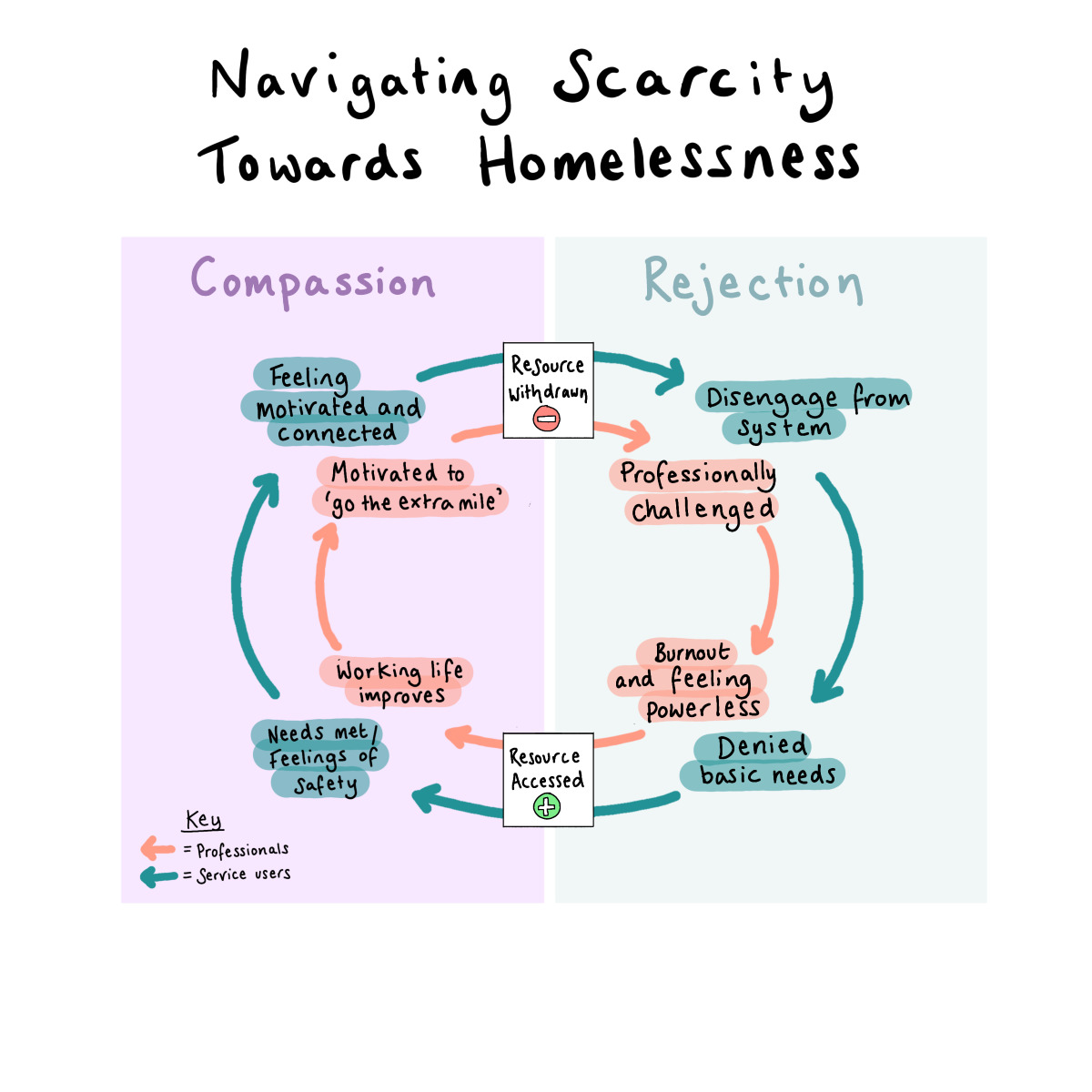

It was clear also that “gaps” and “hoops” were present, too, for the professionals attempting to provide care as best as they could within a framework that is ultimately too resource-scarce to make a fulfilling impact.

These dual narratives of scarcity were mapped out (below) as a way to visualise these two separate but parallel journeys through a care framework, which are driven by a lack of resources.

Graphic courtesy of Juliet Young

Despite the best efforts of those on the front lines, one focus group participant described how commissioning services for homeless people was difficult. This group “just isn’t attractive to funders” due to stigma and a false perception that homeless people are undeserving of help unless they submit to “care and control” measures set down by services.

Thanks to the invaluable insight provided by all volunteers in the one-to-one interviews and focus groups, not only were real-world experiences allowed to take the spotlight, but ground-up recommendations were able to be pulled from the perceived failings in the status quo.

Some recommendations for people developing supports for homeless people include:

- meaningfully examining opportunities for choice

- “hoops” in place that prevent people from getting the support they need

- playing an active role in petitioning for adequate health and social care for homeless people

Recommendations include:

- Systemic improvements such as sharing basic information, streamlining referral pathways, and supporting agencies to cooperate, would improve the practical day-to-day running of many agencies and community organizations.

- Accessing support for difficulties with drugs and alcohol was incredibly difficult for the participants in this research. Reducing barriers to this type of support and exploring novel approaches to substance use may be of benefit.

- Understanding and utilising the significant value in retaining talented and experienced professionals working in services. Providing adequate support to care for these staff is also essential yet not currently widespread in the UK.

This research can form the basis of meaningful progress, both in real-world care systems and in further study of such issues as they exist today. Thank you to all of the participants who took part and to the organisations that supported this piece of work. Thanks to Juliet Young @creative.clinical.psychologist for the illustrations.

Find the full summary document here. An empirical paper based on this research is currently under review and will be published in due course. For more information, click here.