To work in the homelessness sector a year into the Covid-19 pandemic is to feel so many things at once – grateful to have a job, resentful about how much you’re doing for so little, deeply sad about preventable death, sometimes buoyed by the rewards inherent to the work, frustration at the lack of political will to solve homelessness, and tired. So tired.

Folks working on the frontlines of homelessness were already struggling before this even started. Many of us have never figured out how to process or cope with the overwhelm and grief involved in this work, or more precisely, we have not been offered the support or framework to do so. In this context, the pandemic hit. It has hit homeless people, and by extension, the homelessness sector harder. Crisis is the rule, not the exception.

We went past “burnout” a while ago and now need a new term for what it feels like to continue to show up for crisis work in 2021.

“Burnout” describes the feeling I felt when I chose to stop working in shelter environments after about a decade. I was once a lit flame, and then I was a wisp of smoke. The term is an apt metaphor for the feeling. But the term “burnout” doesn’t properly capture the workplace phenomenon or the forces and structures that create it. When decision-makers don’t direct money, ideas, or people into addressing social crises, the workers and the clients end up compensating for that lack with their own labor. The word for that is exploitation.

When our labor is exploited, we get busier and busier. Every time we are given some new task to deal with, it seems too much at first, and then we adjust. Covid is like that, times 10. It’s all the same work, plus PPE and sanitizing and educating and managing our own and others’ anxiety and trying to get people housed with an even higher sense of urgency.

The busier we get, the more work becomes a series of tasks to complete. We’re grieving a lot this year, but one of the things we’re grieving in the field is rarely having the time or energy to communicate the feeling of care. Yes, we’re still providing care as best as possible, but communicating care is a different thing.

Working in a youth shelter – if I had time – I would make a point to serve dinner like I was in a restaurant.

I brought the residents’ plates out to the tables rather than sliding plates through a window. Unless a resident was giving me that “Gimme my food already” vibe, I would try to engage more personally: “Veggies or no veggies? And can I get you a glass of water? What kind of fruit do you like? Are you just getting back? How was your day?” This was a way for me to communicate care, warmth, and respect.

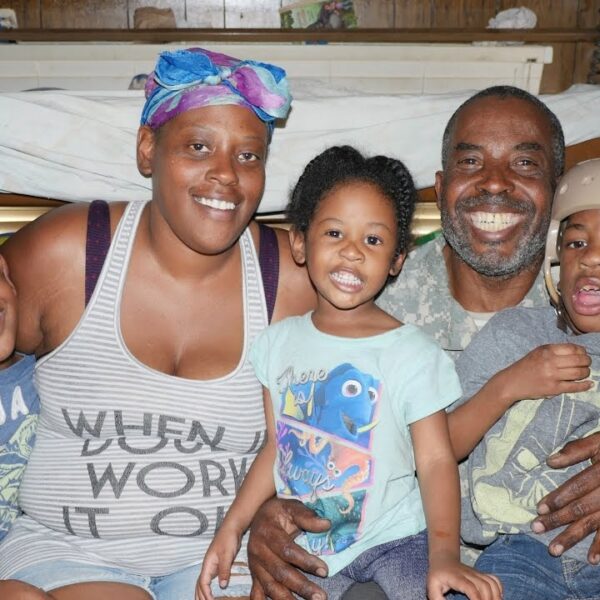

Creating moments of connection is the most important thing we can do to build safety. With connection, we coregulate – we calm nervous systems. We say, “You are welcome here. We want you here.”

It’s so hard to do now, at a time when people need that connection more than ever. Whether service user or provider, our nervous systems are activated – the threat of an unseen virus compelling us into “alert” mode.

Breaking down crisis work into a series of tasks to complete is a pretty effective way of managing “alert” mode, in a way.

In areas hard-hit by the overdose crisis, even saving a life has turned into just another task in the series. My colleagues working in safer consumption sites tell me how different intervening in an overdose feels compared to their first time. The first overdose intervention was terrifying, a flood of stress hormones followed by a disorienting comedown. Now saving a life is a sequence of steps that can be mechanically completed: Monitor – Oxygen – Naloxone – Standby to call 911 – Ambulance.

Well, until the sequence of steps doesn’t actually save the person. Until we lose another person in a preventable death. Unfortunately, dealing with death can never be reduced to just a task, but it is part of the work. And the losses haven’t become any less devastating.

My colleagues may argue with me on that.

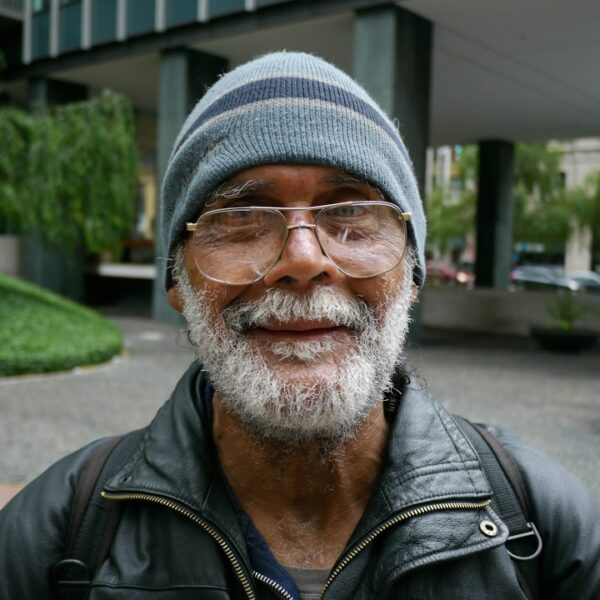

They would say they are not as affected anymore because they no longer get to know the clients as they once did or because they’re approaching work in a more disconnected or even numb way. In my view, that means the devastation has already occurred. Now they’re moving through the rubble, shellshocked.

I honestly can’t say that we can achieve well-being even amid these crises. We can wake up tomorrow, and all these crises will still be raging. That means we take care of ourselves only to be re-wounded. To be stressed out and tired and grieving is a totally normal response to this reality.

I think it’s important to remember that we still have agency in the context of exploitation. We have our ethics. We have the ability to connect. We can give ourselves tons of self-compassion. We can focus on the fact that our “tasks” relieve suffering, even when a meaningful connection is rare. We can feel our grief rather than trying to bypass it or “logic” ourselves out of it. We can say “no” more work when our capacity has run out, whether that “no” is for a colleague, a client, or a boss. We can sit with the feeling that we would really like to “save” each other from these converging crises but can’t.

We are great, but we are not heroes. We are just hardworking people who give a damn. But we do need to give a damn about ourselves, too. It’s necessary to look after ourselves with the same love and dedication we look after service users.

When this pandemic is over, we will go back to “normal.” We might feel relieved by the increase in time to connect with our clients more meaningfully. The work that once felt like “too much” (because it was) might feel easy. We might be able to fit in a bit more self-care.

This is not a good thing: I worry that a workday that feels “better than pandemic times” will demotivate us from advocating for systemic change. But our normal was not normal; it wasn’t enough for homeless people, and it wasn’t enough for those trying to help. We will have to continue to demand the respect and resources that we and our clients need.