Brockville, Ontario, Canada, is well positioned as a tourism city.

Nestled on the St. Lawrence River and proclaimed the “City of 1000 Islands,” Brockville is rich with visual flare and majesty. Home to Canada’s first railway tunnel, a multi-million-dollar maritime education centre, and enhanced city amenities, Brockville is a city rich with culture.

As a community conveniently built on the Montreal-Windsor corridor with rail access and international borders at their fingertips, Brockville should also be rich with opportunity.

However, while this author’s love for my former hometown is evidenced by long-time advocacy and public service, even I worry about the most vulnerable falling through the cracks.

With a population of approximately 22,000, the community is also not without its share of poverty, desperation, and need. For a tourism-centric campus that promotes an above-average quality of life, landlocked in 22 square kilometres, sometimes the appearance of a tent encampment is perceived more as an eye sore than a misery signal—cracks in the foundation of a picturesque city that has so much to offer.

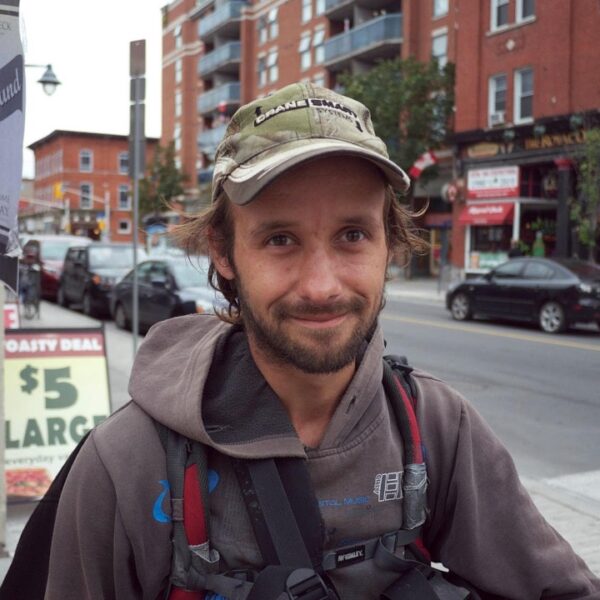

Talking with Brockville Streetfriends collaborator and co-founder Mark Darrah about the pre-summer eviction of the community’s most recognized tent encampments, Darrah shared words of anger and disappointment in how his home city is dealing with the ugliness of poverty.

“Long story short, one camp had [existed] without incident for over a year. Another more visible one beside Highway 401 had been in place for about nine months. There was growing outrage from many of the more conservative members of the community who, ignoring the plight of the humans living there, demanded that the camps be cleared because it ‘made the town look bad,'” Darrah said.

A letter to the Ministry of Transportation was pushed forward, and the camp was removed in one very fast-paced moment of chaos and mass eviction.

Darrah attributes the immediacy of the eviction to a summer tourism season that was about to begin.

“Having visitors see the clear evidence of an issue that very few have done very little to address was considered unacceptable,” he said.

Switching gears and taking a moment to explain his ongoing relationships with some of the City of 1000 Islands’ rough sleepers, Darrah can’t help but reminisce positively.

“Despite having reputations for being dangerous places, I’ve had nothing but positive interactions at the various local camps in Brockville. The occupants, though generally guarded at first, tend to be very proud of the home they have made for themselves,” Darrah said.

“In some cases, they have been excited to show off the things they have acquired, built, or repurposed. In one case, I was even invited to take pictures. It helps that I’ve been involved with the unhoused community for a couple of years. I wouldn’t advise just walking into a camp uninvited and unannounced, just as you wouldn’t open a stranger’s front door and walk inside.”

Recalling one specific tent community that was torn down in the June eviction, Darrah referred to it as “a marvel of makeshift engineering, with fences, a very safe and well-designed cooking area, sanitation, and even security cameras.” He recalled the camp’s founder was happy to explain in detail how he rigged an entire compound for safety and security.

When asked who he feels owns the lion’s share of responsibility regarding the treatment of tent camps, Darrah admits he can’t answer that without some serious community reflection.

“In short, I think we are all responsible. All levels of government have failed people for decades, creating and exacerbating the crises of inequality, housing affordability, and addictions and mental health.”

“We struggled for years to even get government to acknowledge we had an issue with homelessness in Brockville,” he continued. “No location within the city limits was deemed acceptable for a homeless shelter. Even the local warming centre is outside of the city on a property on the outskirts. This forces unhoused people to travel several kilometres each way to arrive during a set window of time, hoping there is still room,” Darrah said. “Sometimes when the facility is full, they end up leaving with an apology and a bag of snacks, with the best case of being sent back on the street at 8am to walk into town.”

Painting a grim but honest picture of the challenging climate many communities face, Darrah eventually settles on one segment of the population that he feels could use their powers for the greater good.

“If I had to say who is most responsible for the treatment of tent camps and unhoused people more broadly, I would say it is the members of the community who see tent camps and struggling people as a blight. They always tell me they really care about ‘those people,’ but then go on to tell me they just need to be ‘somewhere else’ and that there are lots of jobs available. As if a person who is struggling to survive the day while living with unresolved trauma or mental health or addiction issues is going to be able to just show up and get hired,” Darrah said.

Although he’s the first to admit that some do care about the situation, demonstrating their warmth to the city’s homeless population in meaningful ways.

“The problem is that people are constantly putting pressure on the government to ‘just get them out of here,’ which is leading to camps being destroyed under the guise of helping,” he said.

When pondering the moral dilemmas that spring from a community appearing less than empathic to its homeless populations, Darrah stops short of blaming those who desperately wish to help. He said that helping others should not be up for debate simply because their traumas or behaviours appear unpleasant.

“Ultimately, I don’t know how to make you care about other people if you aren’t inclined to do so. I think, like most groups that are the victims of intolerance, part of the solution is contact,” he said. “It’s much harder to dismiss all unhoused people as ‘criminals’ and ‘junkies’ when you have talked to people who are homeless because they fled a violent domestic situation. It’s harder to be prejudicial after meeting someone who is fully employed and is striving to better themselves but can’t get a place to rent because of a spotty credit history.”

“Education about the issue is incredibly important,” Darrah continued. “Learning that many youths are homeless because their religious families have discarded them for being LGBTQ+ is eye-opening for many.”

While those moments of impact have been meaningful for Darrah and the Brockville Streetfriends, he admits that not everyone is a friend.

“I’ve been told that I’m a ‘piece of shit that enables crackheads’ for giving food or supplies to someone who has nothing but the clothes they are wearing,” Darrah said. “I tend not to engage with people like that, except sometimes on social media, so that people who are struggling know that not everyone in the community hates them.”

When asked about his feelings about tent communities versus the many alternatives, Darrah admits that answers aren’t cut and dry.

“Tent communities are certainly not as safe as a home or apartment,” Darrah admitted. “However, some of the people in tent communities band together to keep each other safer than they would be if they had to sleep alone.”

Well-versed in the political pressures people face while trying to govern a small town, Darrah shies away from placing blame directly on local decision-makers. He believes that while adverse decisions like clearing tent camps are ultimately the wrong decisions, he also admits that pressures felt by local politicians responding to their communities make it difficult to make complicated decisions simpler.

Instead of criticizing anyone further, he uses this platform to extend an olive branch.

“If I could get them to come with me, I’d love to bring them to a camp where they could meet the people that slash and burn policies have impacted,” Darrah said.

However, with cold weather fast approaching, Darrah is the first to admit that kinship and empathy are no longer enough.

“Situations that were merely uncomfortable or miserable can quickly turn lethal,” he said. “Needing to get in from the cold leads vulnerable people to make unsafe and unpleasant choices, such as staying in abusive relationships or trading sex for a place to stay. This has led to fatal outcomes for a few of our most vulnerable individuals.”

When asked what involvement in his local homeless outreach initiative has meant, Darrah said:

“Brockville Streetfriends is at once a source of pride and deep sadness. I feel good that interacting with people facing housing insecurity and homelessness has helped me learn the depth of the problem and to join with other concerned community members to try to assist where possible. Seeing the direct impact on the lives of vulnerable people is incredibly rewarding. That said, some of the life stories I hear are beyond heartbreaking, and knowing that we are not solving the problem, merely lessening its impact can be very discouraging.”

“My current schedule leaves me with less availability to assist, and the worsening problem compounds my sense of helplessness,” he continued. “I continue to provide as much support as I can, but it never feels like enough.”

And with people dying, it never feels like enough because it isn’t. Everybody is famous in a small town. Here’s hoping that one day small towns will be famous for eradicating a problem and not just redistributing it.