The Work Left Undone

Barbara Poppe’s middle name might as well be “Protest.”

Poppe has spent more than four decades trying to end homelessness at the local, state, and federal levels. She’s most well-known for her work developing the first federal strategy to end homelessness when she led the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness during the Obama administration. But she wasn’t always a policy wonk.

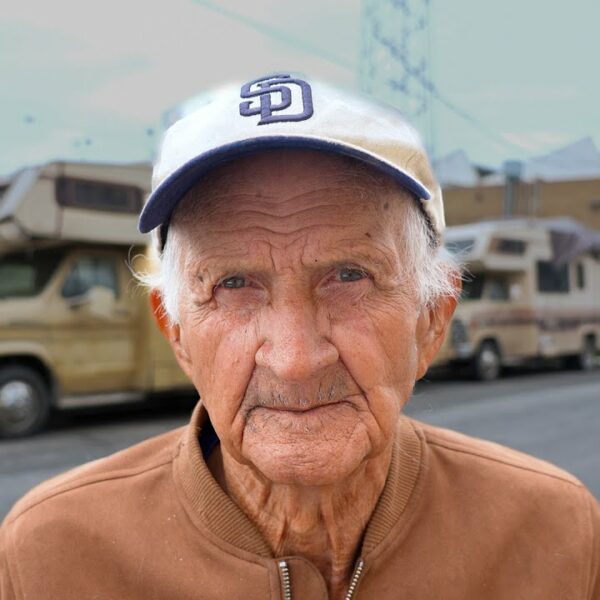

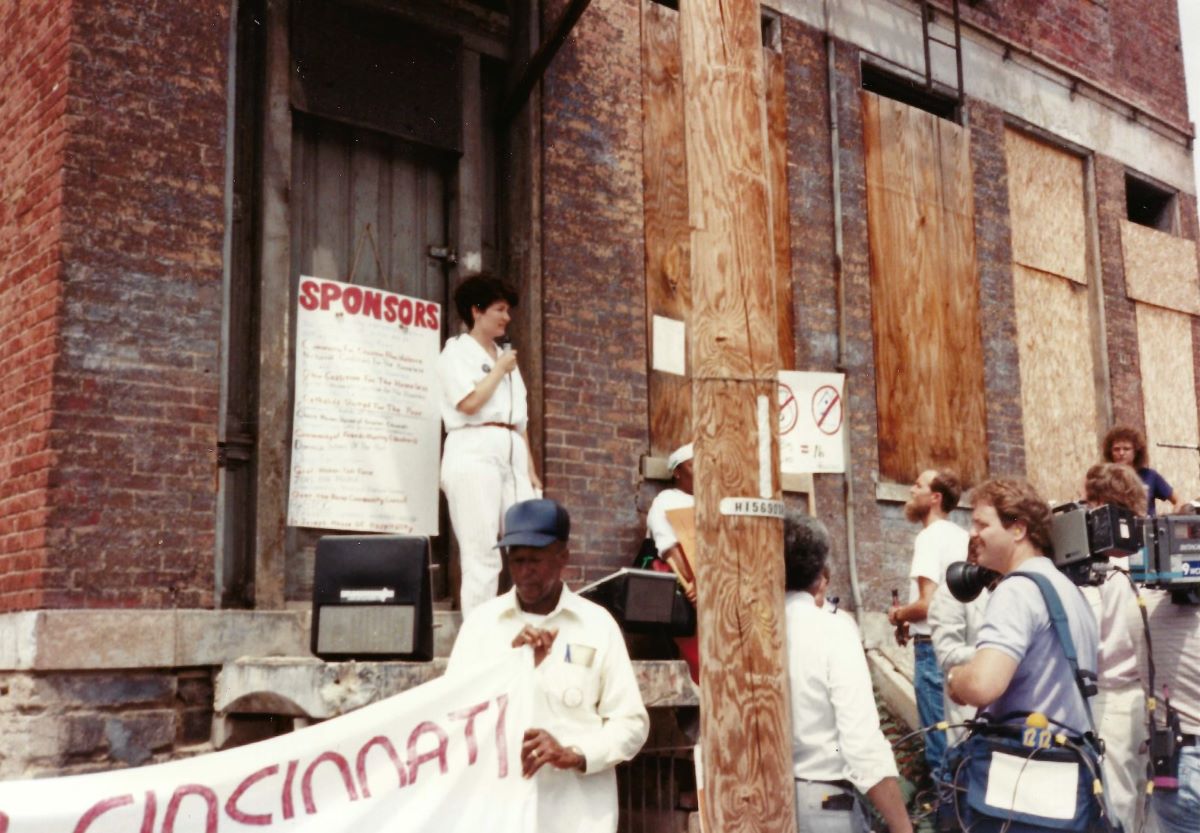

Barbara Poppe speaks at Take Off The Boards protest in Cincinnati during the 1980s

Poppe began her career protesting on the streets of Cincinnati in the 1980s and eventually moved into nonprofit leadership positions where she helped develop a whole-person service model practiced by many nonprofits. Today, she owns and operates an eponymous consulting firm that works with clients ranging from nonprofits to government entities on strategies to end homelessness.

It’s not uncommon for nonprofit executives and former government officials to join protests. However, Poppe said she didn’t expect to have to be protesting for the same things today that she was when she got into this line of work in the 1980s.

“It’s heart-wrenching,” Poppe told Invisible People.

Poppe, 66, was one of hundreds of advocates who showed up to protest outside of the Supreme Court on April 22 during oral arguments for Johnson v. Grants Pass. The case could decide whether cities can punitively punish people experiencing homelessness with fines and fees when no shelter is available.

Watch our documentary on Grants Pass’ Cruel War on Homelessness

Protests surrounding policies like public camping bans and coordinated encampment sweeps have become more common over the last several years.

Forty-eight states have at least one law on the books that either prohibits or restricts the conduct of people experiencing homelessness, such as sitting, eating, lying down, or sleeping outside, according to the National Homelessness Law Center. In 2023, at least 11 state legislatures debated bills to increase penalties for people who break these laws.

This criminalization trend is happening at a time when roughly 653,000 people are experiencing homelessness on a single night, a total that’s grown by 12% year-over-year. There are also more families with children and seniors sleeping on the nation’s streets than ever before, as rising home prices and rents make it harder for low-income earning households to afford housing.

It’s also a sign that even though advocates have created sweeping changes in how homelessness is addressed, Poppe said there is still a lot of work to be done.

Bethany House Services: Poppe’s Journey Begins

If you want to know why Poppe is so passionate about solving homelessness, just ask Linda Seiter, executive director of Caracole, a nonprofit that connects people living with HIV/AIDS with housing and other services.

Seiter was leading another HIV/AIDS service organization in Cincinnati, Ohio when she and Poppe met in the mid-1980s.

Poppe was working with Bethany House Services, a nonprofit that provides emergency shelter, food, and other supplies to women and children experiencing housing instability. Bethany House opened with an operating budget of around $25,000, and its programming was inspired by the Catholic Worker Movement, which sought to house people experiencing homelessness immediately.

Poppe is credited as one of the nonprofit’s founding members. Since then, the organization has served approximately 450 people per year with its housing services and has an operating budget of more than $36 million, according to its latest tax filings.

Poppe started working with Bethany House while on leave from the University of Cincinnati’s medical school, where she studied epidemiology.

Poppe said she left after having a “frustrating experience” with a newborn who was admitted to a pediatric hospital she was working at with a condition known as “failure to thrive.” Doctors and social workers eventually discovered that the child’s family lived in a vehicle, even though the father worked full-time. That was when she recognized the systems designed to help families like this tried to make broad generalizations fit individual cases.

“That experience definitely kind of blew my mind because the medical approach didn’t get to the whole person approach until many days after the baby had been hospitalized,” she said.

Treating People With Dignity and Compassion

When she worked at Bethany House, Poppe lived in the house with the women and children experiencing homelessness that the nonprofit served. When the shelter first opened, residents were allowed to stay up to six weeks at a time, which was three times longer than they could stay at the local Salvation Army shelter. Poppe said this experience solidified her belief that people experiencing homelessness should be treated with dignity and compassion, two values that have underlined her work ever since.

“From the moment I met her, I knew she could do anything she wanted,” Seiter told Invisible People. “But she chose to spend her life working in homelessness.”

One of Poppe’s goals in life at that time was protest. She said she became part of Cincinnati’s activist community during her time at Bethany House.

She was inspired by activists like Stanley “Buddy” Gray, who led the fight against gentrification in the city’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood in the 1970s. She was also inspired by the work of Maurice McCrackin, a civil rights and peace activist, and Mitch Snyder, a high-profile activist in Washington, D.C., who protested against former president Ronald Reagan’s steep budget cuts for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Bev Merill, the director of housing services at Welcome House of Northern Kentucky, a homeless services organization with locations in Somerset and Maysville, used to protest with Poppe in Cincinnati. They participated in a local “Take Off the Boards” action in Cincinnati, where protesters occupied a derelict building as a show of civil disobedience.

It was part of a Community for Creative Non-Violence campaign to get cities to reuse derelict housing as homeless shelters. Seiter added that protesters would use crowbars and hammers to break into abandoned multi-unit buildings.

“We would just go inside and refuse to leave,” she said.

‘She Was That Far Ahead of Everybody Else.’

Friends and former co-workers say Poppe applied the same fiery passion to nonprofit leadership and policy making.

Poppe helped form organizations like the Greater Cincinnati Homeless Coalition in May 1984. The coalition began as a group of 15 volunteers who met in a church basement. The coalition has a single goal: “the eradication of homelessness in Cincinnati.”

Poppe said the group was initially inspired by Snyder’s work in D.C. Since then, the coalition has grown to include 60 agencies. It has been led by national figures such as Donald Whitehead Jr., who currently leads the National Homeless Coalition.

That work propelled Poppe toward leadership roles at organizations like Friends of the Homeless, a housing support services organization that serves greater Franklin County, Ohio, and the Community Shelter Board, a continuum of care funded by organizations like HUD and the Franklin County Board of Commissioners.

Barbara Poppe talks to the press and attendees at Take Off The Boards protest in Cincinnati during the 1980s

These jobs helped her get the attention of the Obama administration, she said, because they were some of the first organizations to use a data-driven approach to ending homelessness.

Minnesota Housing Commissioner Jennifer Ho worked with Poppe at USICH as her deputy director between 2009 and 2014. She said Poppe “felt the responsibility of being Obama’s point person on homelessness.”

Poppe was known for being a voracious consumer of information.

She would read dense government documents while riding the metro to work. She was always chatting with advocates, policymakers, and members of the president’s cabinet. And she frequently took trips to see what homelessness looked like in specific communities. For instance, Ho said Poppe stayed in Puerto Rico for a week to learn about homelessness there.

“She really wanted to understand what were the circumstances on the ground and what was the environment like for the providers who put in the work down there,” Ho said.

“I always used to joke that if you understood what Barb was doing now, that was what you should be hoping to do five years from now because she was that far ahead of everybody else,” Ho said.

Opening Doors, the first federal strategy to end homelessness, is an example of how far ahead Poppe was thinking at the time, Ho added.

The plan was designed as a roadmap for the 19 council agencies coordinating the federal response to homelessness. Ho said Poppe’s “encyclopedic knowledge” of both the human and systemic elements of homelessness helped the rest of the team digest the wealth of data, policies, and federal regulations they navigated through to complete the report.

At the time Opening Doors was released in 2010, roughly 640,000 people experienced homelessness on a single night, according to federal data. That total has since swelled to more than 653,000, which includes a 12% spike between 2022 and 2023 as the coronavirus pandemic ended.

‘Power Concedes Nothing Without Protest’

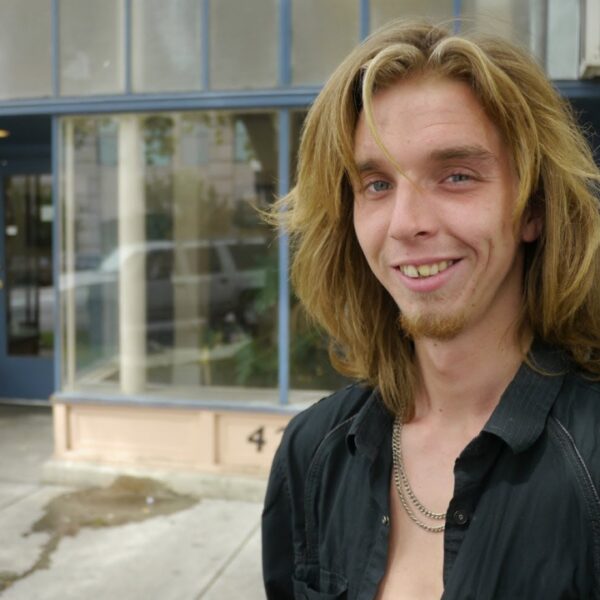

There was a chill in the air on April 22 as activists, advocates, and concerned citizens gathered at the steps of the Supreme Court to protest. The rally was attended by groups such as the National Homelessness Law Center, the National Alliance to End Homelessness, and several local advocacy organizations.

Inside the courthouse, lawyers for the City of Grants Pass, Oregon, argued that the city should be allowed to punitively punish people experiencing homelessness for sleeping outside when no shelter is available.

Lawyers arguing on behalf of Gloria Johnson, a woman experiencing homelessness in Grants Pass who challenged the law, argued that this violates the Eighth Amendment protections against cruel and unusual punishment. Given the court’s conservative supermajority, protesters were concerned that it would rule in favor of Grants Pass and thereby overturn the Martin v. Boise precedent set in 2019.

“Power concedes nothing without protest,“ Donald Whitehead, the executive director for the National Coalition for the Homeless, said during the rally. Whitehead and Poppe were activists together in Cincinnati during the 1980s.

Poppe meandered through the crowded sidewalk, stopping to greet people she’s worked with over many years at the state and federal level. Almost everyone she talked to relayed the same message: “It’s hard to believe we’re still out here fighting for this.”

To Poppe, homelessness has become much more “brutal“ since she first started her advocacy career. People live in more extreme conditions like large encampments and federal parks.

Still, politicians and local leaders also seem to disagree about whether the issue is theirs to solve, Poppe added. That wasn’t the case in the 1990s and 2000s when there was broad bipartisan agreement that homelessness needed to be solved, she said.

In a sense, that is why there seems to be so much work left to do to end homelessness despite nearly four decades of dedicated advocacy and work by people like Poppe. Well-funded organizations also promote a “tough love“ approach to homelessness to convince people not to sleep outside.

“It seems to me that there are many people that have become upset about the visibility of homelessness. And rather than believing we have a collective responsibility to support people who need help, instead, society seems to think that locking them up, charging fines and enforcement citations against them is the idea,“ Poppe said.