Can Music Break the Incarceration-Homelessness Cycle?

Reading Prison Policy Initiative’s 2018 research into former prisoners and rough sleeping in the US is grim. It’s a hidden housing crisis in the literal sense. You could argue the most depressing part of the study is the fact this recent work provided the first ever estimates on the number of people going from life behind bars to life on the streets.

Those who served one jail term are seven times more likely to become homeless compared with the overall population. The rate almost doubles for people incarcerated twice or more. The problem is worst among people of color and women, and during the first two years following release.

It’s no stretch of the imagination to assume this contributes to the revolving door prison system. Survival situations lead to desperate decisions and serious consequences, prosecutions are made for offenses like sleeping in public spaces. Even without the immediate risk of life on the streets, housing insecurity is triple the threat to former prisoners as homelessness per se, which can make finding work even more difficult for a group with a pre-pandemic unemployment rate 27% higher than the general public.

It’s the definition of a vicious cycle with several causes. Open and discreet discrimination and mental health problems should never be far from the conversation, nor should a lack of preparedness for life after prison. Many return to the community only to struggle navigating the systems that are supposed to help them with housing and employment, systems that rarely seem to work as they should in the first place.

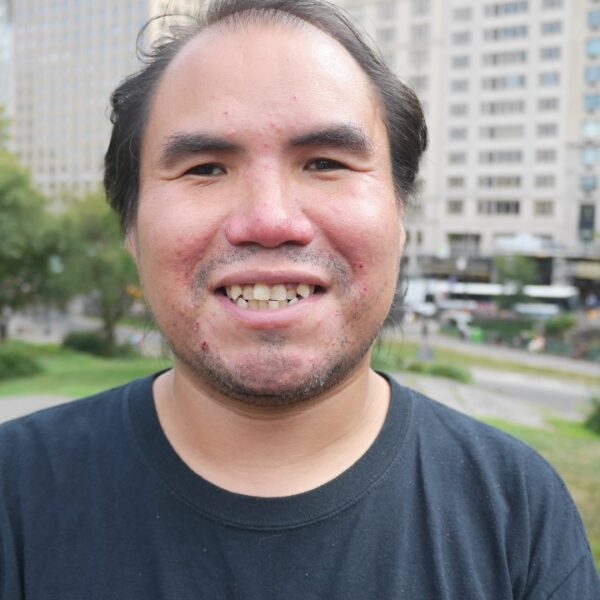

Carl Dukes vividly captures the situation in his song, Paper Bag.

Using delicate piano blues as a backdrop to his first days out of prison after 31 years, it’s the story of a man who was in his 60s spending months moving from shelter to shelter because housing he was promised never materialized. The title refers to the bag his possessions were in, and feelings of disposability. The track spotlights the irony of trying to start over while falling through a threadbare safety net with no stable ground to start on. It also features the spectacularly soulful voice of Apostle Heloise.

“One of the things that happens inside prisons is most times the programs the system offers do not prepare one to be released,” Dukes said. He explained that while incarcerated, he was involved in work to improve the quality and relevance of programs while trying to educate fellow inmates politically and economically.

“When I came out, after listening to so many stories from guys saying they were taking advantage of the system, it was clear they thought they were. But that’s actually what the system is designed to do for you in terms of welfare and stuff. They wasn’t really up on it, but I’d listened to this stuff. I got pretty hip to it.”

Eleven years after his release, Dukes works with The Fortune Society, signposting incarcerated people and former prisoners to the kinds of services and networks they need, but may not be aware of.

Before COVID-19 hit, he was also a regular performer at a New York City music cafe, where he met Fury Young.

“On a Thursday I sing there — Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, stuff like that,” he explained. “Fury heard me sing. We got to talking and he said ‘maybe you can write a song about your experience when you got out. We can sit down and write it’. I said to him, ‘we don’t have to do that’, and pulled out my diary. When I first got out I kept this diary, and basically the song came out of what was written in there. It’s as simple as that.”

Die Jim Crow recording sessions.

Paper Bag first appeared on the 2016 Die Jim Crow EP, which owes its title to a project Young started in response to the human rights crisis inside American prisons, and in particular the systemic racism and impact on Black people and communities. Today, what started as a concept album comprising 26 songs about life before, during and after prison has blossomed into a full-blown record label that has worked with close to 60 former and current prisoners of various backgrounds, and five institutions. It’s now preparing to unveil the Territorial LP from seven artists inside the Colorado Territorial Correctional Facility, following Assata Troi by BL Shirelle, the imprint’s first solo artist album.

Fittingly it was released on June 19th, commemoration day for the end of slavery in the US.

“Early 2019, I had gone on a trip south where me and my engineer recorded 25 new artists who were incarcerated, including Albert Woodfox (one of the Angola Three who was in solitary confinement for 43 years),” he said. “It was a very formative experience for me, for many reasons, but mainly the sheer number of people who were involved, their stories and histories. It became so clear that this is no longer one album.”

“In one case a 10-member group formed from the sessions, the Masses,” Young said of how Die Jim Crow the label was formally born. “I got home and realized it was a record label, brought it to the board, BL Shirelle and Maxwell Melvins, formerly incarcerated collaborators of mine who have official roles. They were all down and the rest is history.”

The prison system is no stranger to creative projects, and the benefits of well-run programs are very real. But what sets Die Jim Crow apart from many is its makeup. This is a real record label selling real music by artists who have lived that experience. People who have lived that experience inform its direction.

Through tangibility and authenticity the imprint can give a voice to a forgotten demographic and change discourse around incarceration. Tracks like Paper Bag are exemplary of how vital the messages are.

“The creative energy behind those walls is locked up, Fury has created an avenue to get it out. That gives people something that they can build positive energy from, and feed off that,” Dukes said of Die Jim Crow.

He shared his thoughts on creative programs for prisoners in general, and their ability to change perceptions and perspectives:

“It creates a personal, what’s the word, a personal resource. When people understand the kinds of things that they’re about now, whatever it was that led them there is not the first thing on their mind anymore. I always say, ‘you are not the crime you committed, you’re something else’. Whatever that is, you’re not that. Once you realize that you start to see the worth in people.”