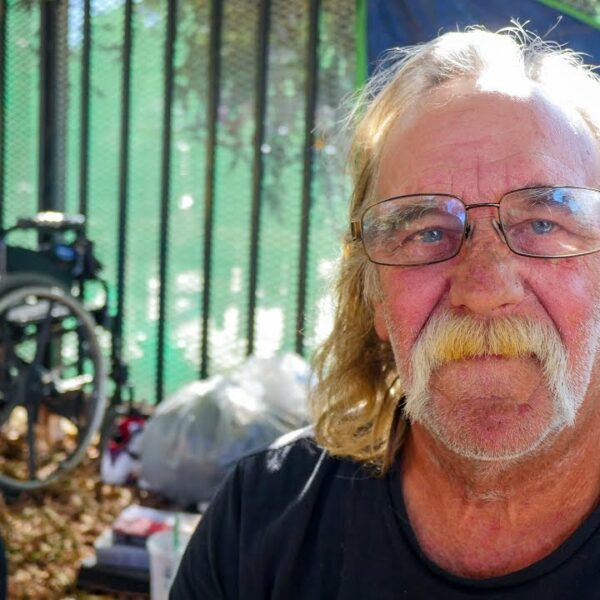

Raymond Weatherspoon, 66, spent more than 20 years traveling across the U.S. building skyscrapers and power plants before he retired in 2016. But soon after that, his path toward stable housing took a few twists and turns that left him needing a helping hand.

Weatherspoon moved from his home in southern California to Nashville, Tennessee, to be closer to his family in early 2022 after he started losing his eyesight. As an Air Force veteran, he was able to get rental assistance through the federal HUD-VASH housing voucher program. But finding a suitable apartment proved to be tougher than Weatherspoon thought.

Over the next two months, Weatherspoon couch-surfed at his younger brother’s house and slept in vehicles and at transitional housing centers before he and his caseworker with the V.A. found out about Glastonbury Woods, a 144-unit supportive housing community in Nashville for people exiting homelessness. Weatherspoon applied for an apartment and was approved four days later.

Since then, Weatherspoon told Invisible People that he’s been able to improve his health by going to doctor’s appointments more regularly. He’s also improved his financial health by opening a savings account and improving his credit score, which was one barrier he faced when he tried to move into more traditional apartment complexes.

“I’m overwhelmed to be in a place like Glastonbury at this point of my life,” Weatherspoon said. “To receive all the help they’ve given me, it makes me feel like everything I went through was well worth it.”

Cities Experiment with a New Supportive Housing Model

Glastonbury Woods is one of a handful of supportive housing units for people exiting homelessness that cropped up in 2022. They were developed by a national nonprofit advocacy group called Community Solutions, which also operates similar buildings in cities such as Santa Fe, New Mexico; Denver, Colorado; and Atlanta, Georgia.

Each apartment complex is designed to be a mixed-income community, with half of the units reserved for people exiting homelessness and the other half reserved for people earning up to 60% of an area’s median income.

They were developed using a social impact investing model that generates financial returns for investors only when specific social goals have been met. For example, the social impact fund that Community Solutions opened specifically intends to decrease veterans and chronic homelessness locally. So, investors will only get a return on their funds if those social goals are met.

What makes the supportive housing complexes different than other similar projects is how the properties are managed. Property managers at the complexes funded by Community Solutions use what’s known as a “property management plus” model whereby the managers are empowered to act as quasi-case managers for their residents. This can include helping connect tenants with additional services or contacting their case manager when a tenant needs additional support.

Rosanne Haggerty, CEO of Community Solutions, an advocacy nonprofit working to end homelessness, told Invisible People that this model empowers property managers to be problem solvers instead of focusing solely on who pays their rent on time.

“This model really links the building and property management teams, and really makes the building a local hub for reducing and ending homelessness,” Haggerty said.

Supportive Housing Provides Unmatched Benefits

Glastonbury offers a range of benefits for veterans like Weatherspoon. It’s close to public transportation, which is how Weatherspoon gets around town, he said. Weatherspoon added that he’s been able to get new lighting installed to help him see shapes in his apartment, even though he still needs a seeing-eye cane to move around.

“It’s nice to have my own private space—a place I can really call my own,” Weatherspoon said.

Nashville Mayor John Cooper described Glastonbury’s supportive housing model as an “innovative step” toward accomplishing the city’s goals of “creating a true housing-first model” to help people experiencing homelessness into a stable living environment.

Building more supportive housing for people exiting homelessness has become imperative over the past two years as home prices and rent increases threaten the housing stability of millions of renters.

For example, Nashville’s median home price has increased by 15% between November 2021 and November 2022 to more than $460,000. The city’s median rent for a two-bedroom apartment also increased by 13.2% in November up to $2,063 per month, which was one of the nation’s greatest year-over-year changes.

The Need for New Housing Models Has Never Been Greater

According to the Census Bureau’s latest Household Pulse Survey, nearly one-third of renters say they could face eviction within the next two weeks because they are behind on rent. That number has been sticky over the past year despite the proliferation of rental assistance programs in states across the country.

Meanwhile, a growing number of military veterans are sleeping outside instead of in shelters, which puts them at risk of experiencing exposure-related conditions like hypothermia in the winter and heat stroke during the summer months. Data from the Department of Housing and Urban Stability shows a 10% decrease in the number of veterans sleeping in shelters between 2020 and 2021, the largest single-year decline since 2015.

Haggerty said social impact investing might provide one way to build more supportive housing because the funds can be deployed in about 90 days compared to the four to five years it takes to build homes using a tax-credit financing model. Community Solutions also focuses on renovation projects instead of building new apartments from the ground up to save time as well.

“It goes without saying that we need more housing in this country,” Haggerty said. “But we also need to get more creative about how we provide supportive housing for people who need it. Not everyone can survive by simply putting a roof over their heads.”

How You Can Help

The pandemic proved that we need to rethink housing in the U.S. It also provided additional support and protections for vulnerable renters, especially people exiting homelessness through supportive housing.

That’s why we need you to contact your officials and representatives. Tell them you support keeping many of the pandemic-related aid programs in place for future use. They have proven effective at keeping people housed, which is the first step to ending homelessness.