Refugees Staying at Homeless Camps Wait on an Imaginary List to See the US Government

You have probably never heard of Juanita, but she does bicultural events the for Juarez-El Paso corridor. She took my husband, Paul, and me across the border to Juarez, Mexico, in late October. We passed by dental offices, optical shops, a hospital, a pharmacy, a few restaurants, other normal urban features, and came to the reason for our visit: the large, self-assembled community of people from Mexico and Central America who are trying desperately to achieve refugee or legal immigrant status in the U.S.A.

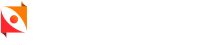

People from all across Mexico, parts of Latin America and even Cuba share their stories as they wait to cross into the United States. Photo by Paul Ross.

About 800 people are living in a makeshift tent city, located in a park close to Puente de Cordova, the toll-free bridge between Juarez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas. Because many of them are fleeing violence, drug cartels, and gangs that they refused to join, they are afraid those who tried to harm them would recognize them if we published identifiable photos of them, so we took no photos of their faces. They gamely consented to let us photograph their hands, feet, and backs.

Camping tents, tarpaulins and whatever else can be scavenged to provide shelter constitute “home,” while people wait to cross the border into the US. Photo by Paul Ross.

They allowed us to look into their small tarp and cardboard shelters, where 5, 7, 10, or even 13 people live in a tiny space with a few mats for sleeping. There are several chemical toilets and they cook over open fires outside. They hang black bags up in the sun to heat water for showers.

When I asked them what they lacked, they said, “heat for the cold nights,” “food and blankets,” “milk for our children,” and “shoes, please, shoes.”

One woman showed us her young child’s only pair of shoes—sneakers so worn at the top that they were almost completely detached from the soles. They come from Guerrero, Durango, Michoacan, Zacatecas, parts of Mexico that are plagued by violence. Many have been threatened and attacked.

We visited with the group from Zacatecas.

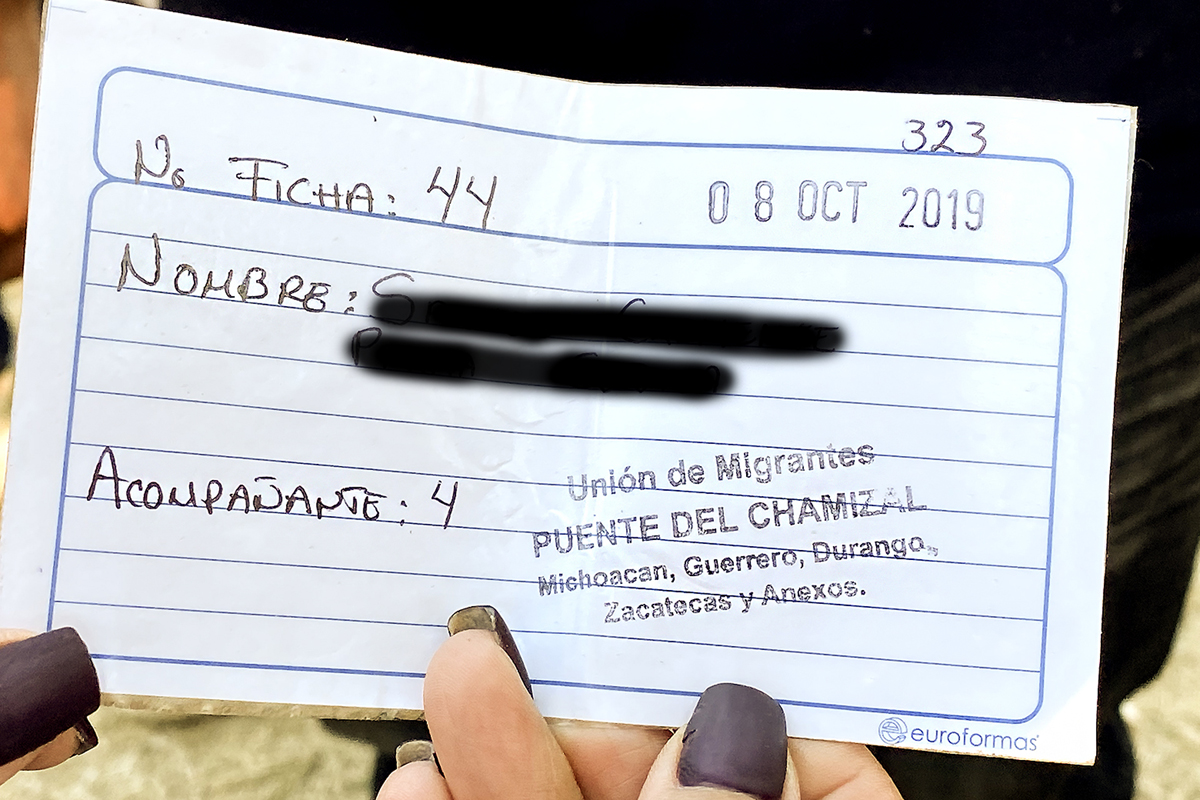

They each have a numbered card, designating their place in line. When we inquired, “what line?” they explained they’ve organized a list that is fair to all; the lowest numbers are first in line to meet with U.S.A. immigration.

But we later learned that the list is a Mexican phenomenon and a sad fantasy. There is no official or governmental list on the American side. It’s like people waiting to enter the castle in Kafka’s nightmarish, absurdist novel of the same name. Only this is not fiction.

Each head of household receives a number indicting a place in line to meet with immigration authorities. Photo by Paul Ross

They wait with numbers on a list they have created that in no way corresponds to the reality of the ever-changing immigration rules that prevent and try to bar them from entering the U.S. “At the border, they tell us they don’t care what happened to us in Mexico. It’s of no interest to them,” the leader of the Zacatecas group told us.

The refugee families left everything behind when they fled their hometowns.

They said that every eight days the Red Cross comes to see them. Some North Americans also come to bring them food. A teenage boy seemed very upset. “Last night, a car drove back and forth here. It was filled with gringos shouting, ‘You fucking niggers will never get into America,'” he reported.

The people of the tent city are freezing, hungry, and desperate, but they don’t want to go into the shelters in Juarez. “We don’t want to lose our place in line close to the border,” they insisted. Most of them have family in the United States, and said they just want to get to them. But other than their places on the lists and their dreams and prayers, they have no concrete plans.

A young father and mother from Michoacan told us that they were fleeing gang violence when they paid about $82 per person to take a bus to Juarez. “We took important papers, some clothes, and some money with us. That’s all. We need toilet paper. Food. Blankets. Shoes.”

Cooking is primitive and food supplies meager in the improvised tent city near the international border. Photo by Paul Ross.

It is very moving how these people, who were strangers before, have self-organized into a community.

They do nothing all day. They hang out and just wait. And wait. They all insisted they don’t want to lose their place in line, whatever they perceive that line to be. They said that, “one family gets in every 10 days.”

Our guide and friend Juanita gently reminded them that they can go to a shelter where it’s clean and there are regularly scheduled meals. But they insisted they are afraid to lose their place. Juanita seemed both sad and angry. This was the first time she had been to the tent city and, like us, she found it wrenching.

She drove us to a Mexican government shelter. The entry is through a locked gate, where a guard wearing a black mask came to greet us. He said that we were supposed to meet with the director, but we were late and the director wasn’t available. He told us to come back in an hour.

Rather than waiting in the car, Juanita drove us to Burritos Crisostoma, where, for $1.80, I ate the best mole burrito of my life. We talked about food, as we chewed the chicken and tried to swallow what we had just experienced in the tent city at the border.

A woman who sat near us told us that she brings hot chocolate and cookies to the tent city and reads aloud to the kids. “The tents started a month ago,” she said. “Before that, they were sleeping and living in the streets, on the ground, on the bridge.”

She told us that government officials in Juarez say that when it gets really cold, the people will leave the tents and go into the shelters.

Juarez citizens are urged not to help the people living in tents. “They want them to leave on their own. They say this very publically, and on T.V.,” she explained.

We drove back to the shelter, where we were warned that no photos, video, or filming is allowed. We agreed, of course. Outside the shelter is a large mural of a Mexican hand shaking hands with South American countries.

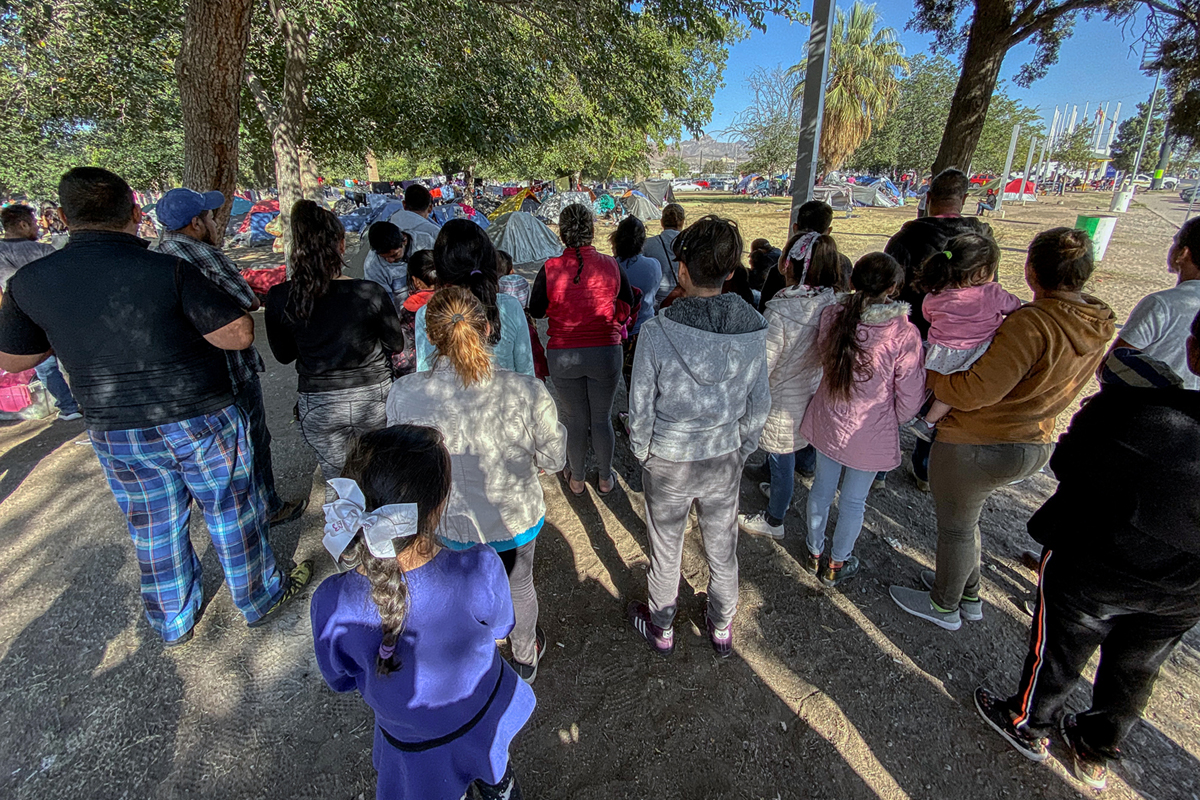

Inside the shelter we met a man who fled Honduras on foot, and sometimes he hitched a ride with a passing truck. He said he had a date with a judge in two months, and, like all the others, he was waiting. “The Mexicans discriminate against us,” he said. “They tell us to go back home.”

Mexican government shelter, a former warehouse. Photo by Paul Ross.

A week before our visit, the shelter got beds. Prior to that, they were sleeping on the floor.

“Every night we eat tuna,” he sighed. “That’s all we eat. Tuna and water and two tortillas. Lunch is a little meat and beans. For breakfast we have scrambled eggs. We get one blanket, and I am cold. We get one pair of sheets. I have a sweater and my son has a shirt. At night they shine lights in our eyes to check on us. We are cautious and I am afraid to say much more. I know people in Dallas. I hope to get there.”

We met a 15-year-old boy from Guatemala who was in the shelter with his father. They also fled on foot, hitched rides with trucks, and took a bus. He said they fled violence and were extorted for money. They had no work. He complained that kids in the shelter had hepatitis and diarrhea.

The director is an open-hearted, intelligent, sensitive young man, who is friendly with the people in the shelter and genuinely cares about them and their situation.

There are 597 people in the shelter, he said, and they will open others in Mexicali, Laredo, and Tijuana; this was the first one. He confirmed the beds just recently arrived. The Mexican government pays for everything else. He explained why they are acceding to the U.S. government’s request that they keep the immigrants on the Mexican side.

“Trump said that if we don’t keep refugees, he will levy progressive taxes. If he does that, the Mexican government will collapse in two months.”

The director explained that the shelter houses people from Venezuela, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Peru, Panama, Cuba, and Ecuador. Some are Mexicans. And he was relieved to report that there is no violence in the shelter.

The Mexican army prepares meals at the government shelter in Juarez. Photo by Paul Ross<

“The people here help to clean, and they form a community. The Mexican army brings and prepares food, and that works well. For breakfast we have eggs, coffee, cookies, eggs with potato or salsa. Always eggs. There is meat and beans and rice and tortillas and lentils for lunch. What the man told you is true. For dinner it’s tuna or sardines with crackers. I have been here since the day the shelter opened. I want to move here (he comes from another city), I am single, 24 years old, and I have a degree in political science. The staff wasn’t trained to do the job, but everyone is pulling together and learning. I am always tired, but I love my job.”

He reported there are classes Monday to Friday. At the end of a month, if the parents want it and if the kids take a test and pass it, they can go to school.

Instead of trying to get into the U.S., they can settle in Mexico where the children can go to school. Only three percent of the people can get asylum. “We aren’t teaching English because we don’t want to create false hopes of their going to America,” he said.

We saw a line of kids going to a computer class. They carried supplies given to them by the Mexican government: shampoo, soap, a towel, toothpaste and a toothbrush. Mexicans donate the clothes they need for the winter. And they are protected from violence and have access to medical and psychological care.

“Ninety seven percent can have a life in Mexico if they wish,” the director told us. “They can get official documents and work.”

He said that U.S. border patrol takes about three families every l0 days. “The ones who are living outside want to stay near the bridge because there is no bureaucracy. If border patrol says tonight at 3 a.m. we will take three families, they are ready to go. They want to be there before people from the shelters.”

To lighten things up for a moment, we asked him if he likes the burrito place where we had lunch.

“They make molé with wheat tortillas and not corn. It’s a lack of respect,” he insisted firmly. Then he went back to something he likes better. “Tomorrow they will have pillows and sheets here. It’s the Mexican government that’s paying for them.”

He asked us not to bring food to the people in the tent community.

“We want them to come here, where the kids can go to school and they can go to doctors.”

As he talked, young children came up to him and touched him gently; we could see they liked him. “It’s okay to give food to the children living in tents, but we want the families to come here to get shelter. People here are fleeing violence. They are afraid of retribution. And they get sent back home. Please, no photos of their faces,” he said.

We gave the director a hug then drove half an hour to a shelter run by the Catholic Church and philanthropies rather than the Mexican government.

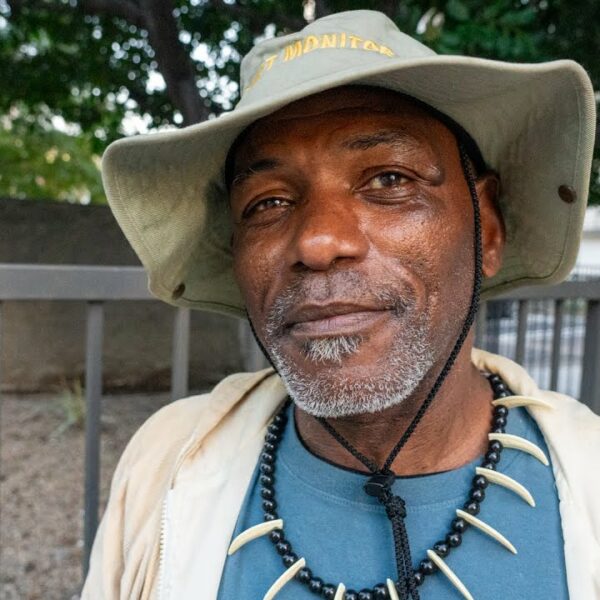

In the lobby, statues of saints are covered with hand-written payers, milagros (charms that are usually used for healings or for votive offerings), baggage checks, ID wristbands. In the words of a man who works there, “they give thanks for their freedom. They are out of jail and not being held any more in the U.S. They are back in Mexico, they are free.”

He said there are about 300 people in the shelter. There is no school, and the food is donated.

“They are supposed to be here for three days, but now it’s sometimes for months. Mexicans only go to the border officials once. They are either accepted or rejected. Foreigners have multiple interviews. Then they are accepted or deported. They go back to the situations they fled. A very small percentage is accepted.”

We went into the cafeteria and met the wonderful, overworked kitchen staff. The cafeteria serves about 440 people for lunch, but can only seat about 100 at a time. Each person eats fast to make room for the next.

“There is only meat if we get a donation. If not, then it’s tuna and sardines with potato and squash. At night, there is milk and rice coffee, potato with chile. We use powdered milk for coffee and hot chocolate and everything else. We mix up and go through 30 gallons of milk a day,” the main cook told us. “I have to invent what we serve each day. Sometimes all we have is bread or tortillas.”

At this shelter, they separate men from the women and children to sleep.

We walked to the sleeping area and saw four bunk beds per room. These are rooms for women and children under eight years old.

In the main outdoor courtyard, mothers played dominoes with their kids. People hung out, not doing much, passing time. Young kids filled one table playing with a few scattered, plastic toys. Everywhere we walked, there were signs supporting refugees and immigrants.

As in the first shelter and in the tent city, we met people who walked and rode with trucks and buses to get to Juarez. They spoke of violence and extortion and shooting children and forced gang recruitment.

About six months ago, these shelters opened up in Mexico. Before that, they weren’t organized for large groups of people who had nowhere to live.

Juanita drove us away from the shelter. We didn’t speak much.

There was a long line of cars waiting to cross back to the U.S.A. We waited about 65 minutes. Around us, men circulated and sold chicharones, m&m’s, and chips with sauce poured over them to drivers. Juanita said the bridge used to be wide open for cars to pass. Now they have added barbed wire on both sides, and restricted the entry lanes.

Juanita pointed out kids who were born in the U.S.A. and live in Juarez. They walk across the bridge on their way back from school in El Paso. Customs and Border Protection took our passports. I asked the border official what his favorite burrito place is in Juarez. He said he never goes there. He used to go as a kid. I told him the name of a place to get a great mole burrito, and he hesitated, squinted, and then smiled, “I’ll have to try it.”

This was our third visit to the Mexican border over the past year. We went twice when we were in southern Arizona. It is the first time that any border patrol official said he had been to Mexico or might be interested in going. Every other one I asked—and I asked more than 50—said he had never gone to Mexico and had no interest in doing so.

I was very sad that night, as I am while I write this.

It is below freezing and snowing in the city Juarez tonight, and I worry about the desperate people living in those flimsy tents. I keep thinking that if there were legal work permits for the United States, this whole nightmare might go away. Many businesses in America can’t find enough workers.

In Juarez and elsewhere on the Mexican side of the border, people are literally willing to die to get in. If there were legal permits with clearly defined rules, regulations, and accountability, it could be the beginning of an end to the unfolding Kafkaesque nightmare.