When you envision the “typical” homeless person, do you see a middle-aged man on a freeway holding up a cardboard sign with a story of woe emblazoned in magic marker? Or do you see an empty desk in an elementary school classroom, an unworn uniform, and a child’s name that’s always called but never present?

While both of the aforementioned scenarios are tragic, according to school records, the second description – the child absent from their assigned classroom – is much more emblematic of homelessness in America.

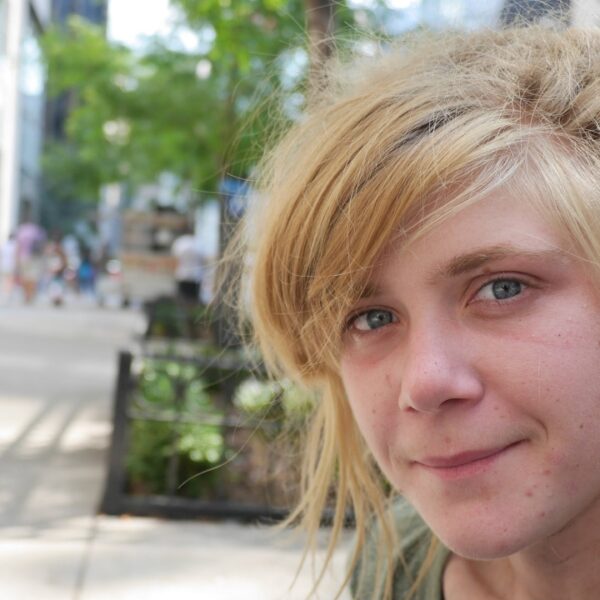

Here at our publication, we sometimes refer to members of the unhoused community as “Invisible People” because we, as a society, look right through them. Houseless humans are more likely to be ignored by their peers, legislators, and the general population. However, on paper, they exist – well, to some extent, anyway.

Many of the statistics you read in the media about homelessness are limited to homeless adults and sometimes unaccompanied teenagers. Because homeless children live in more obscure situations, they are drastically undercounted in government records.

If you really want to know just how many children are actually homeless, you need only look at the school’s records, a database that’s equally important although seldom cited.

The National Center for Homeless Education identified 1.5 million homeless school-aged kids in the 2017-2018 school year, a number that School House Connection states is an 11% increase from the 2016-2017 school year, the year that broke the record for most homeless school children in history.

Incidentally, according to Early Childhood Homelessness State Profiles: Data Collected in 2018-2019, another 1,297,513 homeless children are under the age of six, meaning their homelessness is likely not reflected in school or government records.

If you’ve sharpened your pencil and done the math, you see that we’re swiftly approaching the 3 million mark for children experiencing homelessness.

With Millions of Children Left Behind in Homelessness, How Do They Legally Attend School?

The answer, sadly, is that many unhoused children don’t attend school, which is why their homelessness can be quantified through their absences. However, a little-known fact is that children facing the hardship of homelessness still legally have a right to education either in their school district of origin or, if they are in the shelter system, then the school district where their homeless shelter is located.

The Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act Gives Unhoused Students the Legal Right to Education

In 1987, when awareness of the homeless crisis was increasing, Congress passed the Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act. This act and subsequent legislation have gone on to ensure that students’ educational rights are upheld – at least on paper.

Currently, the act functions under a slightly different name, the McKinney-Vento Act, and features a few changes to the original law. In brief, the McKinney-Vento Act ensures the legal right to education for “students who lack a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence,” a criterion that lacks precise definition but typically includes:

- School-aged children in substandard housing

- Children forced to move in with relatives due to economic hardship, loss of housing, natural disasters, or because they’re fleeing domestic violence

- Shelter residents

- Runaways

- Children in transitional housing or transitional living communities

- Displaced students living in hotels or motels

- Children that move into emergency shelters after departing from the juvenile detention system

Under the law, local educational agencies, often referred to as LEAs, are tasked with identifying youth experiencing homelessness and providing support, services, and strategies to foster educational growth.

According to the Department of Education, school liaisons should work in tandem with child welfare agencies, child advocates, resource parents, case workers, and, in some cases, lawyers to ensure that education is provided in a manner that suits the best interest of the child.

Disruption of education due to homelessness is not ideal and should be avoided if possible. However, if a student enduring homelessness does miss multiple marking periods of attendance due to a lack of stable housing, even in cases where the student was a runaway or in the juvenile detention system at the start of the school year, they are still covered under the McKinney-Vento Act and have the right to return to their school of origin or the school located near their current temporary residence.

School of Origin vs. Changing Districts

In many instances, sudden changes in housing status can force a newly homeless student to need to relocate or force a homeless student to need to move from one emergency shelter into another emergency shelter, hotel room, or motel room.

In many cases, regardless of the need to relocate, remaining in the school of origin is in the child’s best interest because it instills a sense of consistency. However, suppose the school of origin is too far away. In that case, the unhoused student has the right to transportation to their school of origin or enrollment in the district near their temporary residence. This should be determined based on what is best for the child.

Barriers and Loopholes in the System

Many homeless students are reluctant to identify themselves as homeless. Many LEA liaisons face difficulty deciphering which students are in an unhoused situation. This results in students missing out on McKinney-Vento services because they either don’t realize they qualify for them, or they don’t know the services exist.

Runaways and students fleeing domestic violence might avoid authority figures altogether. Thus, in a world where education is a cornerstone, homeless children are building futures on a shaky foundation. Some of the barriers to success that exist for this population include:

- Residency and guardianship requirements for school enrollment that conflict with the McKinney-Vento Act

- Disruption and delays in placement and evaluation

- Lack of transportation to the school of origin or the school of choice

- Lack of health or academic documents due to loss or delay

- Lack of coordination between school district administrators, students, and other institutions

- Lack of access to services

- Social stigmas attached to homelessness

- Inaccessibility for chronically unhoused families and more

Talk to Your Policymakers About Homelessness and Education

Only 64% of homeless students ever graduate from high school, a staggering number that’s 13 percentage points below low-income students and more than 20 percentage points below students from middle-income and high-earning families. This perpetuates a system of homelessness and poverty, a revolving door of empty desks and unsharpened pencils.