In a world where the word epidemic is broadly applied to any number of emerging trends, America’s opioid crisis stands head and shoulders above any other drug-related issue the nation is facing. With more than 130 people dying daily from opioid-related drug overdoses over the past few years, we are undeniably in the throes of an opioid epidemic.

Tens of thousands of people die from opioid overdoses annually, many of whom were initially prescribed opioids by their doctors. Despite the addictive and dangerous nature of the drug, they are prescribed quite frequently. The Center for Disease Control reports that as recently as 2017, there were more than 50 opioid prescriptions written for every 100 Americans. “In 16% of US counties, enough opioid prescriptions were dispensed for every person to have one.”

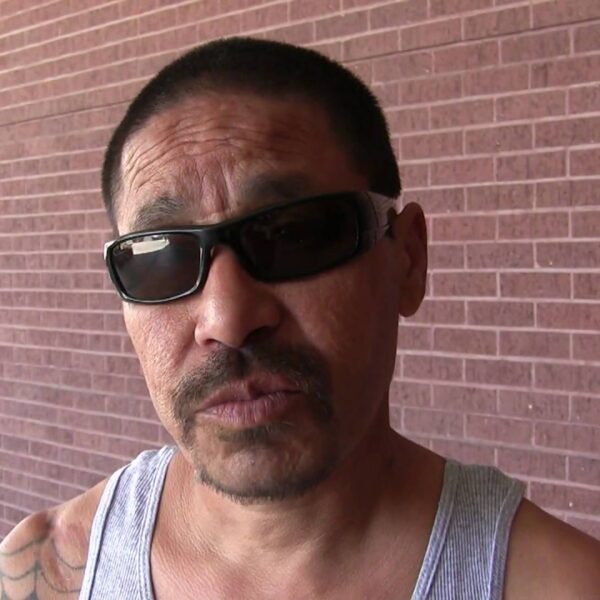

Those numbers are harrowing. Beyond the numbers, though, are real people suffering real pain. Chances are you personally know someone affected by opioid addiction. And while opioid addiction is tragic in any demographic, some people are more at risk than others.

The City of Brotherly Love Has an Opioid Problem

Philadelphia has the nation’s worst opioid crisis of any big city, and their homeless population is most vulnerable. Opioid overdose deaths among the city’s homeless people has tripled in less than a decade, from 43 in 2009 to 132 in 2018. City officials predict that 2019’s numbers will be similar.

Those 132 lives lost among Philadelphia’s homeless in 2018 represents 59% of all opioid overdose deaths. Little wonder officials say people experiencing homelessness are far more likely than others to die of overdoses. Why?

Liz Hersh, director of the Office of Homeless Services, describes it as the result of a ‘perfect storm’ of increased homelessness and the opioid crisis. “The people who are really suffering the most and have been hardest hit are the people who started out with the least.”

Hersh’s explanation is one that homeless people are familiar with. Increased exposure means increased risk of developing addictions. People who are under-dressed get cold more quickly. Those with a weaker immune system get sick more easily. People earning minimum wage are affected more significantly by an expensive phone bill than higher earners.

Many of Philadelphia’s homeless live in the Kensington community, the heart of the crisis. Officials explain that the city’s younger homeless population is more likely to be addicted to opioids than alcohol or other substances. Users flock to Kensington for the relative security of using around others. Many users carry the reversal drug Narcan to revive those who overdose.

So, are homeless people more likely to develop an opioid problem? Or are opioid addicts more likely to fall into homelessness?

Both, actually.

Drug usage is a slippery slope that can rob victims of resources and render them homeless. On the other hand, homeless people may be experiencing intolerable levels of pain, and opioids form part of a self-made pain management plan that makes their day-to-day easier to endure.

What Can Be Done?

If admitting that one has a problem is the first step, then there’s some solace to be taken in the fact that Philadelphia city officials are acutely aware of the opioid issue and how it’s affecting their homeless brothers.

Mayor Jim Kenney made strong statements to close out 2019:

“The City has taken extensive local action to fight against this national crisis, both through the Mayor’s Task Force to Combat the Opioid Epidemic and the Philadelphia Resilience Project, as well as through suing opioid manufacturers.”

Hersh doubled down on the mayor’s statement, saying:

“Homelessness is not an unsolvable problem—even when it is opioid related. It’s a public health crisis with a straightforward solution: making sure that everyone has a safe, affordable place to call home. Housing ends homelessness and saves lives. It is the foundation for recovery.”

That last statement is key. Housing is the foundation upon which recovery is built. To that end, the city is increasing the number of low-barrier beds—shelters that don’t require sobriety to enter. House homeless people first. Then work on treatment. With any luck, the city’s most vulnerable won’t be for long.

Philadelphia officials encourage any residents who need treatment for addiction to call 888-545-2600. Help is available 24/7. Philadelphians can also contact a street homeless outreach team by calling 215-232-1984 if they know of someone in need of shelter or other services.

Photo by Marc Schaefer on Unsplash