The Scales Begin to Tip Against Homeless People as Children in Elementary Schools

National Homelessness Law Center Board Member Khadijah Williams Offers New Approach to Education in IP Exclusive Interview Below

The dehumanization of homeless individuals is a significant and abhorrent problem in our society. Most people believe you can only become homeless by being lazy and that lazy people don’t deserve to be treated as humans. People will give money to certain charities and fight for specific positive change in the world, but won’t give money to a panhandler. And it’s not just because they think the panhandler will use the money on drugs and alcohol. There is a genuine belief that homeless individuals are simply unworthy of help.

First of all, being lazy doesn’t make you a bad person. EVERYONE deserves a home and enough money to support themselves. Secondly, homeless people are not lazy. Many homeless people work multiple jobs. As Ahmed Ali, an advocate for homeless people, recently tweeted: “No one hustles harder or is more industrious than poor folks trying to survive a system that actively tries to harm them daily.”

Poor folks are not lazy, they are exhausted. No one hustles harder or is more industrious than poor folks trying to survive a system that actively tries to harm them daily.

— Ahmed Ali (@MrAhmednurAli) December 13, 2022

National Homelessness Law Center Board Member Khadijah Williams agrees, adding that homeless people who don’t “participate in traditional capitalistic forms of grind” aren’t lazy either.

Is someone who is depressed or has PTSD lazy? Of course not.

ALL homeless people experience trauma to an unimaginable degree compared to someone who has been housed their whole life. And even without the trauma-induced mental health issues, there is what Williams calls an “invisible grind” that homeless individuals face. That of constantly having to plan when and where to go to the bathroom, eat and sleep. It takes up a lot of energy.

It’s horrendous that we must explain that homeless people deserve to be treated equally. No human deserves to be subjected to torture (in the form of frostbite, which can happen even in warmer climates) and untimely death.

Williams is equally disturbed by the dehumanization of homeless individuals. Her story of overcoming homelessness to attend Harvard was featured on Oprah. Williams also shared her story in a recent opinion piece in The Hechinger Report.

“When you are homeless, and this is me speaking from my own experience, you’re not seen. You don’t exist. There is assumed to be something wrong with you,” Williams said. “All of these messages are out there, everywhere, about how homeless people are sub-human. It’s absolutely disgusting and terrifying. I still have challenges with my own sense of worth and self-esteem because of how I was treated as a homeless child. It still impacts me – that’s how bad it is.”

When asked how we can humanize homeless people to those who don’t see them as human, Williams encouraged Invisible People to continue doing its “amazing” work of “getting stories out there about homeless people from their own words.”

She added, “I think we need a similar sort of initiative to what we had that made the gay rights movement go so quickly. People talked about someone they knew who was gay. People are about connection – you sway people through personal narratives. [We need people to] speak out about their experience with a family member or a friend experiencing homelessness so people know it can happen to you, it can happen to someone you know and love, it has happened to someone you know and love.”

It is urgent that everyone embrace homeless individuals and the reality that being homeless is not their fault.

The way things are now, working hard doesn’t guarantee an escape from homelessness.

Williams is determined to debunk the myth that everyone in America can make it if they work hard enough. Yes, this means that what we know as the definition of the American dream is a myth.

Williams believes she was able to make it out of homelessness because she suppressed her trauma and was able to be what society viewed as the “good Black child.” The current system doesn’t do right by those who cannot suppress their trauma, resulting in so many homeless children becoming dehumanized homeless adults through no fault of their own.

Williams is now the national director of policy and advocacy at Lift, a nonprofit that provides direct cash, stress reduction, and community networking to parents to end the cycle of poverty.

She was previously the senior manager of family and community engagement at Rocketship Public Schools, a group of schools in the Bay Area, Nashville, Milwaukee, Washington, D.C., and Texas. Rocketship believes giving parents and teachers equal control over school decisions is the key to helping homeless children succeed. Their method is called the School Site Council model.

A critical practice that Rocketship carries out is having teachers visit each student’s home to meet the student’s parents. Williams says that if a student doesn’t have a home, the teacher and parents can meet at a coffee shop or another location. What’s important is that the meeting is outside the school.

“If your first meeting is at the school, that’s not an even playing field,” Williams said. “That’s like an authority figure and then the parent. But if you’re meeting somewhere outside the school, then you have a situation where it’s an even playing field, and you can engage as individuals and see the human side in each other.”

Williams was kind enough to answer some questions about how to educate homeless children better so that every one of them makes it out of homelessness, as she did.

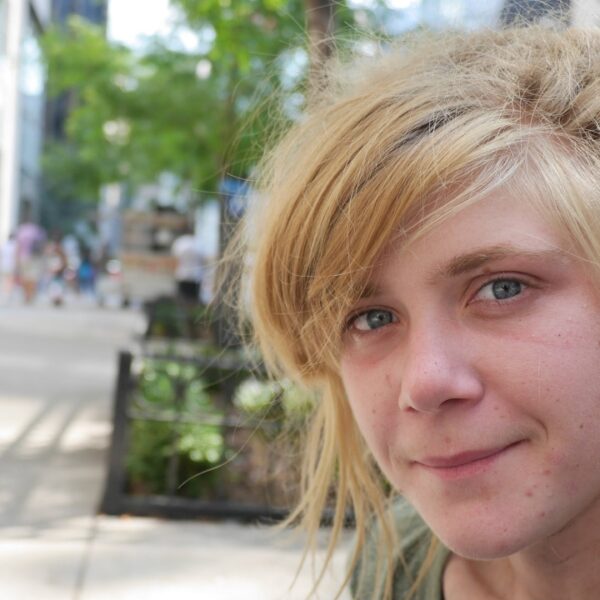

Khadijah Williams, a board member for the National Homelessness Law Center and former senior manager of family and community engagement at Rocketship Public Schools.

An Interview with Khadijah Williams

Invisible People: Can you expand on why trauma caused by homelessness can make it more challenging to have academic success?

Khadijah Williams: “I’ll give you an example. If you are a child who doesn’t have access to clean clothes because you spend nights in a bus station – this has happened to me – and you go to school with the same clothes on, ‘Does anyone else know?’ ‘Do I smell?’ ‘Are people talking about me?’ The kids are talking about me. Like, ‘Ew, you’re wearing the same clothes, ew, you nasty,’ or ‘Ew, you gross.’ That’s stress.

If a child is hungry, hasn’t eaten because the child doesn’t have access to food, they can’t focus on the lesson because their stomach is growling – it hurts when you’re really hungry.

If you’re a child who doesn’t know where you’re gonna live the next day, you go from one school to the other. One day – this happened to me – you might be in San Diego; another day, you might be in Los Angeles. I don’t know what school I’m gonna be in! I don’t know what street I’m gonna live on! What’s the point of turning in my homework if I don’t even know where I’m gonna be.

Not to mention, do they have access to health care? Do they have access to glasses? Do they have access to dental?

All those things are challenges when you’re a homeless child. And that creates undue stress on the child where they can’t focus. Studies have shown that stress changes the ability of your brain to be able to focus, to handle stress. There’s a strong connection between conditions like ADHD and trauma. So trauma can literally change your brain such that it’s harder for you to learn and harder for you to develop appropriately. And then you can develop mental health problems as a result of having that extreme amount of stress, which makes it even harder to focus.

Not to mention not having a place to study because you’re homeless. Not having a consistent way to get to school, not being able to build strong bonds because you don’t know how to because you’ve moved so many times. You’ve never engaged with kids your age.”

IP: With succeeding being harder for Black children because of systemic racism, can you talk about how not being the “good Black child” can hurt one’s chances of succeeding?

KW: “So take two children. So you have me, one child, who, if I’m stressed out, I basically dissociate. I’m not gonna think about my homeless life; school is an escape for me. And so I’m able to focus and I’m seen as quiet. I’m not acting out. I don’t get in trouble, I’m not fighting. And then I’m a ‘good Black child,’ the teacher is more likely to see me as a good student, and then the teacher is more likely to see me as worthy of help.

Even with my scoring high – I scored in the 99.99 percentile in third grade – even doing that, even loving reading and reading at a college level by the time I was in elementary school, teachers still assumed things about me. They said, when I got that score, ‘Oh, she must have cheated.’ So that still happened to me even though I was a ‘good Black child.’

Take another child whose stress is not internalized like mine was, but externalized. They get into fights. They yell and curse out the teacher because they don’t know how to express themselves because they have so much stress. They don’t turn in their homework because they’re like, ‘What’s the point? I’m not gonna be here anyway.’ That child will be labeled as a child who is not worthy of success.

That’s what happened with my little sister. She got straight Fs; she didn’t do her homework, she got into fights. They said, ‘I wish your sister was more like you. She’s not gonna amount to anything.’ My sister’s smarter than I am. She now has a college degree; she now works in child care. She’s more organized than I am, she has stronger EQ than I do.

Even with that, even with her being smarter than me and having all these things that I didn’t have, because she externalized her anger, there are these messages that were told about my sister: ‘We don’t think she’s going to graduate high school, she’s gonna end up in jail.’ All these things were said about my little sister, and she believed them. And that’s scary! And what about all the children who don’t have a big sister who’s like, ‘Um, no.’ She had me, and it still was really rough.

There’s so many kids who don’t have a big sister who’s like, ‘Forget all of this, my sister’s smarter than I am, I’m gonna support her, I’m gonna let her know that she is powerful.’ Many more kids don’t have that and they’re just labeled as bad kids. They’re suspended more. They’re expelled. They end up in the juvenile justice system. You know about the school-to-prison pipeline.”

IP: Why is involving families in education so important?

KW: “Because families know their children. Families want the best for their children. When you are bringing your child to school for any number of days, whether it’s a day a week or the whole week, you as a parent made a decision to enroll your child in school and to bring your child to school. Parents are invested in their children. That’s the first thing. And when you invest in the parent and the knowledge of their child, then you’re able to work as a partner.

Lack of attendance is something that is a symptom of lack of engagement. If a parent is not bringing their child to school, then that means that the parent does not have a strong relationship with the school or with the teacher. Because if they did, then they would be problem-solving with, ‘How can we make sure the child gets to school?’

And you see evidence that when families are engaged, children perform better, children have stronger bonds with their teachers and the whole school benefits. And so, basically, when you don’t involve families in the education, what you’re doing is cutting off one hand. Why would you only perform with one hand when you could have two? Why would you not use this other resource that you have – the family – and have it all on you?

It’s a whole other person you don’t have to pay for! The parent is free!

It’s knowing that [parents] are the experts on their child and partnering with them and opening up that additional source of resources to help that child. And then multiply that by the number of children that are in that school. There are 1,000 kids in school. So at least 1,000 extra people.

Then there are different familial setups. There could be the grandma, the uncle, the brother. So you have all these people who can support your school. And schools are letting all those free resources go to waste. It’s absurd!”

IP: What approaches can teachers take when working with students who have suffered trauma?

KW: “One big one is having an open dialogue with the family, just talking about, ‘Hey, I want to make sure that I understand your child. Are there any sort of triggers that I should be aware of, anything that has happened with the family that would be helpful to know so I can use a trauma-informed approach? Be upfront with the family about why you want the information.

The second thing is looking at behavior as a form of communication. So when a child is acting out, it’s not about that behavior; it’s about, ‘What is that child trying to communicate?’

For example, if a child always acts out when they’re called on and doesn’t answer the question, NOT using a communication-focused approach would involve saying, ‘Hey, I asked you a question, I need you to respond, and if you don’t respond then you’ll go to detention.’ Whereas if you’re looking at it as communication, you can understand the child always acts out when I call on them. Maybe they have anxiety about being called on. So maybe I should try different things, like maybe try small groups, see if they’re talking that way. Maybe I should talk to the parent and say, ‘Do you know if your child has any anxiety around speaking out.’ Just having a dialogue and understanding the root of the behavior.

The third thing is just being empathetic. How would you treat your own child? Assume that this is a loved one. If we just treated children with love in the way that we would treat our own children, a lot of these issues would go away.”

IP: Do you think there’s a chance the School Site Council model gets adopted by schools outside of Rocketship?

KW: “I think what people are understanding in this post-COVID world is that if you don’t have relationships with families, then you can’t have strong academic outcomes. The parent won’t bring the kid to school. The parent will unenroll from the school.

I think schools are starting to realize that they really need families. As approaches like School Site Council are shown to be a success, I do believe that schools will start to implement it more, because they’ll see it as a way to really engage families and involve families in decision-making such that their schools are stronger and more community-focused.”