Seeing Beyond Our Limited Perceptions When It Comes to Homelessness, Disabilities and Poverty

“Growing up, I always felt that I was born with three strikes against me. Strike one: I was born disabled. Strike two: I was black. And strike three: I was a black male.” – Soulja

When Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr., was born in October 1973, Washington, D.C., was on fire.

This was perhaps the story told around his birth; it still resonates with Soulja today. While the 1960s race-riot fires were extinguished by the time Soulja was born, there are still smoldering issues of poverty and racial injustice. And it would take 50 years for D.C. to introduce the “first-ever” Racial Equity Action Plan, a three-year roadmap outlining actions to “close racial equity gaps.”

Soulja, who has spent his adult life in survival mode, managing to stay out of the shelter system, argues that the festering gaps are too wide to close and that the country is still on fire. “The “system is broken,” he said in a recent interview. “And I don’t think anyone really cares.”

Born without legs or fully formed hands, Soulja has had to navigate in a society where any bit of help from the “system” is considered a “luxury” versus a necessity to move beyond survival, he said.

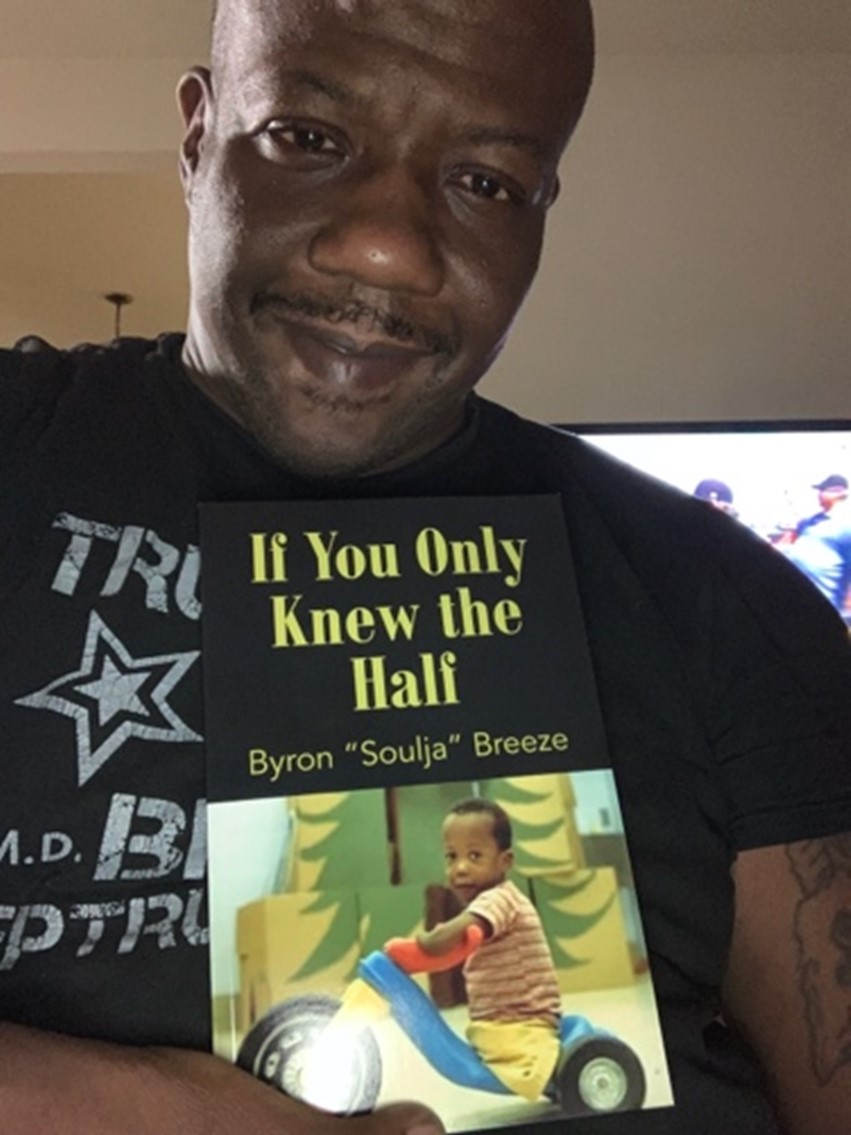

“I entered this world as half a soldier,” he writes in his new book If You Only Knew the Half. “Growing up, I always felt that I was born with three strikes against me. Strike one: I was born disabled. Strike two: I was black. And strike three: I was a black male.”

Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr. at the office at 60th and Madison in New York City.

Photo credit: Alex Berg

Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr. at the office in New York City. A photo of Soulja taken from the early 2000s. Over the years, he’s developed his own distinct style, red headbands, sunglasses, and at times, he wore a suit and a tie. Even then, he was trying to “smash” perceptions.

In 98 pages, including photos, Soulja takes us on his personal journey on how he mentally and spiritually navigates life, then and now. Some of the chapters include: “The Unwavering Spirit,” “A Passion for Motivating Others,” and “Swallowing Pride: A Bittersweet Path to Financial Stability.”

The Bittersweet Path & Unexpected Journey

I met Soulja during his “bittersweet” period. It was the late 1990s, during a time of strong economic growth in the country, perhaps for many. But for Soulja and others who are disabled, many were, and still are, living in poverty.

In 2021, around 25 percent of people with disabilities were living in poverty, compared to 12 percent of people without disabilities, according to research firm Statista—the odds of becoming homeless for a person who is disabled increase exponentially.

At the time, his Supplemental Security Income (SSI) disability benefits averaged around $650 a month. As NPR describes this “hard-to-get federal benefit” was created 51 years ago “to lift Americans who are older, blind, or disabled out of poverty.”

But this benefit has hardly kept up with the actual cost of living over the years. Soulja needed to supplement his income, and the jobs he applied for never materialized. He interviewed, for instance, to answer calls on a crisis hotline – he would have been perfect for that job because he likes motivating and helping people, he said. As for other public-facing service jobs – no callbacks.

His ability to connect with people would help him in unforeseeable ways. Before he came to New York City from the D.C. area, Soulja noticed people offering him money, along with some kind words. “At first, I saw these gestures as disrespectful and rejected their generosity, unwilling to accept pity from others,” he writes.

However, his cousin Greg saw things differently.

He convinced Soulja to visit him in New York, suggesting that occupying a public space in the right location would help Soulja financially. Soulja claimed 60th Street and Madison Avenue, a neighborhood of upscale retailers such as Bergdorf Goodman and multi-million-dollar apartments, as his “office.”

His commute from his cousin’s apartment in the Bronx could take up to nearly two hours, traveling by wheelchair to the bus stop and transferring from one subway to another. Hopefully, the elevators were working. Otherwise, he’d have to climb up the stairs pulling his chair behind him. Then there were several more blocks to go before he reached 60th and Madison to work at least eight hours if not more.

He often arrived at his office slightly before dawn to beat the morning rush hour and get situated. As the sun rose, the food vendors would set up for the day, often offering him coffee and something to eat mixed with New Yorker banter. It’s important to pause and reflect on the word “work” here because surviving takes unrelenting determination.

“People may perceive my work as begging or panhandling when I am just trying to survive,” he says.

How people perceive him is something he’s struggled with since childhood.

“As a child, I hated being stared at and having my picture taken by strangers, and the thought of capitalizing on the attention my disability attracted filled me with mixed emotions. Yet, faced with the reality of my financial situation, I chose to swallow my pride and do what was necessary to support myself,” he writes.

When Life Is a Triathlon, Another Test Is No Problem

Over the years, the office not only helped to support Soulja, but he also forged life-long friendships, from street vendors to detectives to CEOs, all of whom see beyond the “half.” Moreover, it’s given him brief reprieves from the daily grind.

In 2007, The New York Times ran a story, When Life Is a Triathlon, Another Test Is No Problem, that touched on his daily life, including training for a New York City triathlon.

“Life is a triathlon. I got to stay fit in order to do the things I do on a daily basis,” he said in the article.

Training for the Nautica New York City Triathlon consisted of 1,500 meters of swimming, 40 kilometers of biking, and 10 kilometers of running. At first, it seemed ludicrous to Soulja’s friend Steve Drewes, who helped him train, along with Steve’s friend Susie Stark Christianson, a former marine and triathlete.

“At first, I thought, how is he going to do this, is he nuts,” Steve said in an interview conducted during training. “Then I thought, ‘why I would give him my limiting beliefs.'”

Soulja training in New York’s central park.

Photo courtesy of Kathleen Kiley, Michael Patrick Kelly

Soulja training in New York’s central park/at a pool at a local gym. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Kiley, Michael Patrick Kelly

After work, Soulja would train at the local gym, either alone or with Steve and Susie. To prepare for the swimming, they would simulate the unpredictable currents and tides of the Hudson River.

The Challenged Athletes Foundation donated a three-wheel handcycle Soulja could ride. He completed the running segment on a skateboard, pushing himself along. His arms were bandaged to withstand the punishing pushing for miles against the pavement to propel him forward and eventually over the finish line.

Susie, Soulja, and Steve in a celebratory moment right after crossing the finishing line. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Kiley, Michael Patrick Kelly, Andrew Lawton

Three months of intense training paid off: Soulja set a record for his category.

This win and accomplishment set the stage for another “test” – bringing together the Urban Casualties to record in a Manhattan recording studio. Faced with their life obstacles, it would take years of trying to get the Casualties in one location to rehearse and record their original music.

The Casualties, which consisted of Soulja, Wild Child, Cookie, and P-Funk, met at a rehabilitation facility in Maryland. They were young Black men who loved music and dreamed of breaking into the recording industry.

While Soulja had no choice but to adapt to an able-bodied world since birth, his friends became disabled while young men in their twenties. A stabbing, a gunshot, and a car accident paralyze them for life.

Youth, music, and the dream of having their voices heard forged a strong bond of hope and friendship. Breaking into the music industry was hard enough, but hip-hop artists with disabilities were practically unheard of.

Leroy Moore Jr. is an award-winning poet, author, activist, music producer, and founder of the global movement Krip-Hop Nation. Moore also launched the Krip-Hop Institute with the support of UCLA. The Institute will educate the music, media industries and general public about the talents, history, rights and marketability of Hip-Hop artists and other musicians with disabilities. Moore said the Institute will be based in the Black community in Los Angeles.

Leroy Moore Jr., Founder of Krip-Hop Institute. Photo courtesy of Judy Smith

Moore Jr. has spent decades striving to educate the media and general public about the “talents, history, rights and marketability of Hip-Hop artists and other musicians with disabilities.”

Among his many accomplishments over the years in building awareness, in 2020, four of Moore’s Krip-Hop Nation artists received Emmy Award accolades for Outstanding Music Direction for the Paralympic Games documentary Rising Phoenix.

In a recent interview, Moore said, “How he [Soulja] survived was like me, the love and activism of our mothers at an early age.”

For Soulja’s mother, Patricia, it began the moment he was born. The doctors wanted to institutionalize him immediately, but she pushed back and said she was taking her child home, a courageous position against the medical establishment.

“I know he saw that, and that helped him to become the advocate that he is today,” Moore added. “When he brought his friends/rappers with disabilities together, that was the first time he was making his own community. It went from an ‘I’ to a ‘we.'”

A recording of the Urban Casualties’ song, “Rollin’ Rollin’,” featuring Soulja, Wild Child, Cookie, and P-Funk. Cookie – a once-promising athlete – had severe health issues. He would eventually lose both legs due to uncontrollable infections and died in 2018, a casualty of poverty and inadequate healthcare. Filmmaker Michael Patrick Kelly helped shoot and edit the video above with contributions from Andrew Lawton.

Soulja credits his mother and his family with helping him develop resilience.

“I think the reason why he’s so capable is because the way his parents brought him up. They didn’t baby him,” said Dennis Vacante, a now-retired adapted physical education teacher.

He met Soulja in one of his first years as a teacher in Prince George’s County in Maryland. “His parents said, ‘You can do things. You just have to figure it out.'”

Figuring out how to drive a Big Wheel was one of them. He used to call Mr. V, and one day he asked, “Can I ride one of those Big Wheels?” His teacher replied, “Show me what you can do. And he grabbed the steering wheel with one arm, and then with the other one, he pushed the back wheel, and he scooted around just like the other kids. He always found a way, you know.”

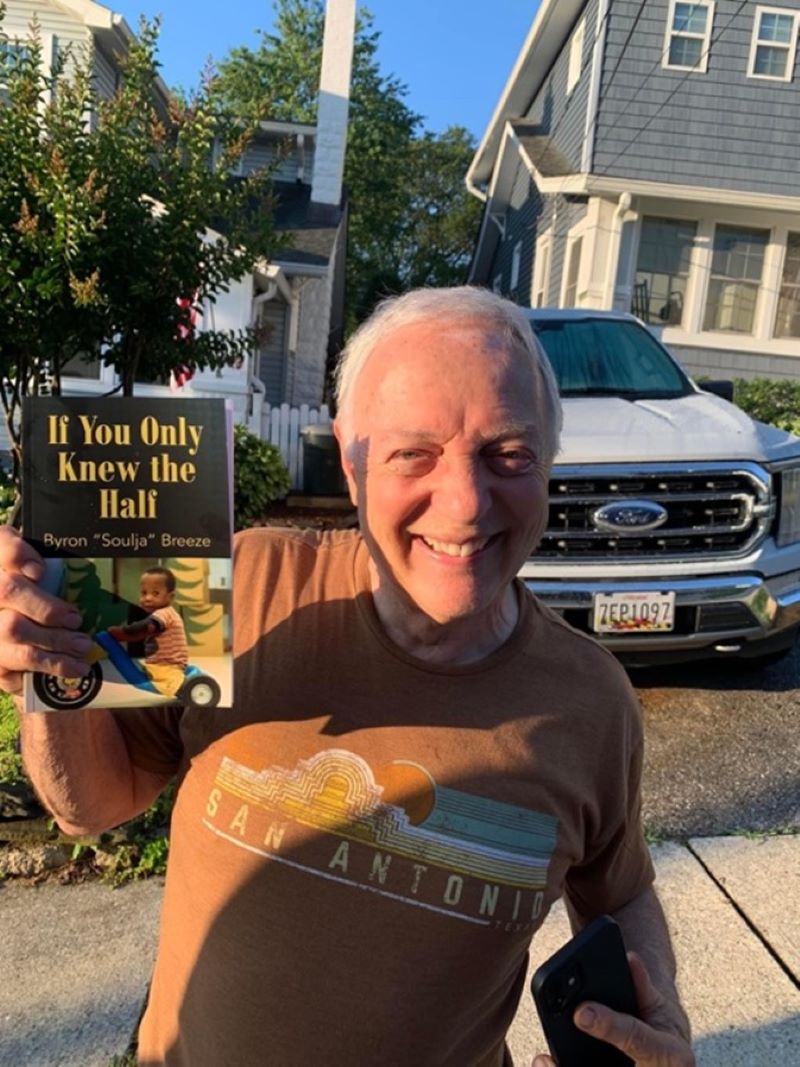

Dennis Vacante holding up a copy of Soulja’s book he personally delivered to him.

Photo courtesy of Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr.

Soulja gets around by truck these days. Like the Big Wheel, vehicles allow him to move around and not depend on subways or a social service system that isn’t always reliable. An adaptive device attached to the brake and gas allows Soulja to drive. In the early days, he used broomsticks taped to the accelerator and brake.

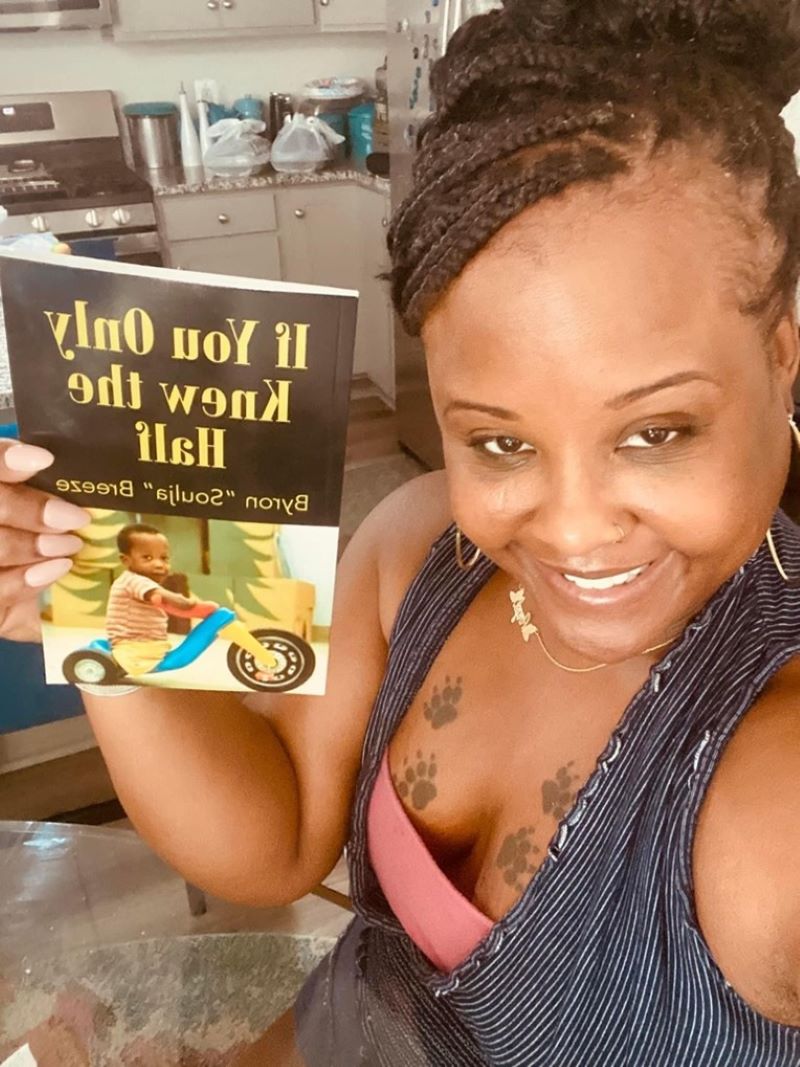

Bridgette Breeze, Soulja’s sister holding up a copy of his new book. She is helping him organize book signings in the Maryland, D.C. area, where their family is from.

Photo courtesy of Bridgette Breeze

The ways Soulja has had to navigate life and support himself may seem unconventional to onlookers.

In “If You Only Knew the Half”, he calls upon us to see beyond our limited way of thinking and viewing the world, including those struggling with poverty, homelessness, and disabilities.

Many only see “half” the story, he said. “Until you open the book and read the first chapter, you can judge all you want.”

In the meantime, he’ll keep on rollin’ rollin’.

A journey about breaking perceptions and overcoming life obstacles. “If You Only Knew the Half” by Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr.

Photo courtesy of Byron “Soulja” Breeze, Jr.