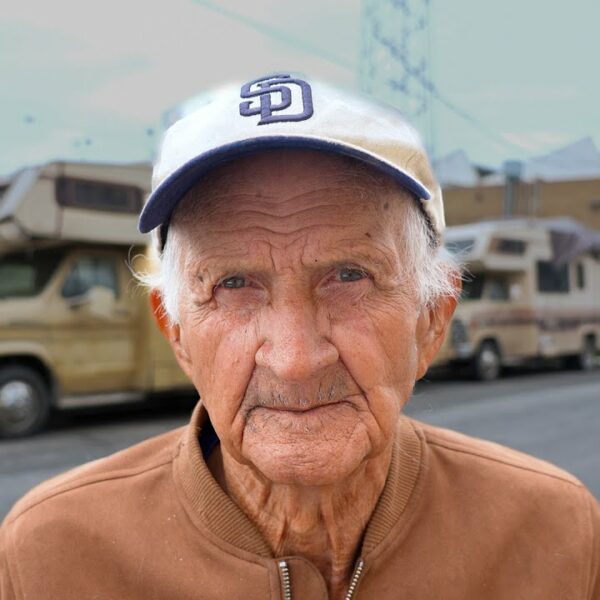

A new report shows why cities often respond to homelessness with criminalization and punitive punishments.

Developed by Community Solutions, a nonprofit housing advocacy group, and researchers from Cornell and Boston University, the report collected survey responses from the mayors of America’s 100 largest cities and found that police departments are largely influential in implementing local homelessness policies.

For example, half of them either do not have city staff dedicated to homeless outreach or rely on their police department for outreach. About three-quarters of police departments with outreach teams, also known as HOTs, formally incorporate police into their outreach efforts instead of relying on social workers or mental health professionals.

For compassion, about one-quarter of mayors placed their city staff dedicated to homelessness in their housing department or a dedicated homelessness agency.

At the same time, the survey found that public pressure to remove encampments is one of the key factors that could “lead cities to pursue more policing-centric policies,” according to the report.

This pressure often comes from complaints lodged by homeowners and businesses about unsheltered homelessness, which “may drive city leaders to focus more on policies such as encampment clearance, fines, and criminal arrests to restrict behaviors associated with homelessness,” the report concluded.

The survey comes at a time when politicians across the country are opting to criminalize homelessness instead of funding evidence-based solutions to the underlying causes of homelessness.

“Overall, police responses to homelessness are overwhelmingly punitive,” Charley Willison, an assistant professor at Cornell University and one of the study’s authors, told Invisible People. “We find this both structurally, in terms of how cities design their responses to homelessness, and systematically when it comes to implementing these policies.”

The criminalization of homelessness has a long history in the U.S.

Some of the earliest documented cases of homelessness occurred in the 1640s, and many colonists often blamed the “moral deficiencies” of the unhoused for their homelessness. According to the Texas Homeless Network, this philosophy is still alive and well today.

The police became more involved in homelessness response efforts throughout the 20th century and now are often “the first (and sometimes the only) point of government contact for persons experiencing homelessness,” according to the RAND Corporation. However, RAND also found that police departments are not equipped to address the underlying causes of homelessness “in a meaningful way.”

Meanwhile, interactions between unhoused folks and the police can be costly.

For example, outreach to individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness can result in police issuing citations for unlawful camping or arresting someone for trespassing. In April, more than 30 unhoused people in Colorado Springs were arrested during an encampment clean-up.

“Punitive policing strategies do not reduce or end homelessness,” the report reads in part. “Such strategies often worsen homelessness. For example, fines and fees make it harder to access employment and social services; in some cases, criminal charges impact peoples’ eligibility for existing social services and housing programs.”

To better address the underlying causes of homelessness, the report recommends that cities fund alternative response programs staffed with mental health professionals, service workers, or clinicians and do not involve the police. These responders should also have specific de-escalation training to assist unhoused folks experiencing mental health or substance abuse crises.

“Alternative outreach teams may also offer benefits for police departments by alleviating pressure to respond to crises like homelessness that require upstream solutions beyond the remit of police departments,” the report states.

Another approach cities can take is re-evaluating how they use citizen complaint portals to address homelessness. The report says that these portals often carry an inherent bias toward the needs and preferences of property owners at the expense of unhoused people. A better way to use these portals could be to route the complaints to alternative response teams instead of the police, according to the report.

How You Can Help

The pandemic proved that we need to rethink housing in the United States. It also showed that aid programs like rental assistance and temporary stimulus checks work when providing agencies and service organizations with sufficient funds and clear guidance on spending aid dollars.

Contact your officials and representatives. Tell them you support keeping many of the pandemic-related aid programs in place for future use. They have proven effective at keeping people housed, which is the first step to ending homelessness.